![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

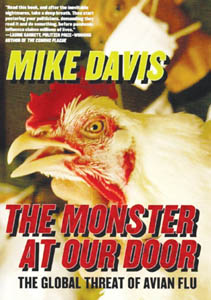

Is It Godzilla? No, it's a chicken. But wait, wasn't there a giant chicken in 'Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster'? Anyway, this is Mike Davis' new book. Flu Me Twice, Shame on Me Could the current avian flu really be as bad as the 1918 pandemic that killed 50 million? And what can be done locally to prepare for it? Master of disaster Mike Davis offers some stinging critique of current policy, and a glimmer of hope. By Bill Forman Mike Davis has a way with disasters, natural and otherwise. His book City of Quartz, published two years before the Rodney King verdict, proved eerily prophetic in its analysis of the historical, cultural and systemic conditions that would soon set Los Angeles ablaze. Ironically, the book had begun life as Davis' doctoral thesis but was turned down by UCLA's history department. Undaunted, Davis has gone on to become one of America's most incisive social historians, earning a MacArthur Foundation Genius Fellowship and consistently training his sites on issues—urban planning, immigration policies, disaster management—that end up making the headlines weeks, months and years later. Now, with avian bird flu in the news literally every day, it should come as no surprise that Davis, now a history professor at UC-Irvine, is weighing in on the topic of the moment with his cautionary tome The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu (New Press; 192 pages; $21.95 cloth). Metro talked to Davis about his new book and the politics of profit and fear. METRO: Some scientists are talking about the current avian flu threat by referencing the influenza pandemic of 1918 that killed as many as 50 million people, but was pretty much forgotten by the public until recently. How do you think a new global outbreak would compare to that one? Mike Davis: Well, that, of course, is the million-dollar question, and the answer is no one knows. But what we do know—and particularly after this very dangerous but breathtaking experiment that was done in August, where, after 10 years of arduous research, they completely mapped the genome of the 1918 influenza and actually turned around in the laboratory and made the influenza—we now know that there are far more similarities than we even suspected before. We now know that the 1918 influenza was a purely avian flu that seems to have mutated and thereby acquired its extraordinary transmissibility. We also now have a much better idea of why it was so virulent. This has baffled people, because even when two-thirds of the genome was mapped, it was still unclear why it was so virulent. Now it's clear that it's actually a collaboration or synergy between two different proteins. Many of its same genetic features are shared by H5N1, so there's an uncanny similarity here. We of course don't know anything about what happened before the emergence of H1N1, the 1918 flu, how long it had basically incubated in birds or other populations. But certainly the results of these experiments in August have only increased the likelihood that there might be a similarity in its virulence. What other factors might contribute to the potential severity of the outbreak? The other side of the equation is the environment in which the virus would operate. And actually the current world in many ways has features analogous or comparable to what favored the disease in 1918: huge concentrations of soldiers, squalid conditions on the western front; all these very same conditions exist in slums around the world, and on an even larger scale. In 1918, there were firebreaks that slowed or interrupted the transmission of the flu, that favored less virulent strains. This time around, so many of the conditions would actually favor the maintenance of virulence from an evolutionary perspective—above all, the ability to jump quickly from person to person, and even if you kill your host you immediately find another host. In other words, the human fuel for a pandemic is much larger and densely packed and conveniently linked by air transit than would have been the case in 1918. George W. Bush is obviously very worried about the perception that he was slow on Hurricane Katrina and now this. But to what extent is he really any slower than his predecessors in responding to disasters and massive health threats? I'm thinking in terms of the response to AIDS; has that track record really been much better? Or is that not a viable comparison? No, I think it's a good comparison. I think that really since the Reagan administration, it's been a disastrous downturn, not just in public health funding, but in priorities and policy. HIV, of course, only got attention because of massive protests and political activism. And I wouldn't rave about what the Clinton administration did, either. I think we've really faced 25 years of decline in funding public health, particularly diseases that affect minority groups and poor people. What's extraordinary about this administration is that its whole shtick essentially is Homeland Security, but everything it does seems to make this country less safe than it was. It has spent billions on this bio-shield program to defend against biological terrorism, most of which is hypothetical. And that has left us in this situation where if there were an avian flu pandemic, none of the vaccines or antivirals would in fact be available for about two years. We're left entirely naked for the next two years. One of your stories on recent disasters was headlined, 'Ethnic Cleansing: GOP Style.' I hate to borrow the language of Fox news, but 'some would say' that's an overstatement. Well, I wish I could believe it was an overstatement, but I think the burden of proof is actually on the other foot. I mean, the president stood in Jackson Square making these heroic promises about New Orleans. And what's happened since then is the federal government has allowed local government to virtually collapse in New Orleans, lay off half the workforce, which impedes the restoration of vital services, and it basically hasn't lifted a finger to re-employ evacuees in the inner city or moved aggressively. Most of the temporary housing that finally has been put up is actually going to workers from out of town who are coming there. You look at the EPA's lethargy and negligence in preparing conditions for cleanup or issuing accurate reports about contamination; the small business administration's utter failure, compared particularly to what happened in previous disasters, to give people the lifelong loans they need to save small businesses, particularly black businesses in New Orleans; the behavior of the insurance industry, particularly vis-à-vis poor home owners. This adds up to another catastrophe fully comparable to Katrina itself. And you simply have to ask: Why is the federal government stalling? Is it stalling because of incompetence? Is it stalling because everything's held up by the Republican right wing's insistence on compensating every dollar spent by some cutback for poor people's social services? Or is there a political design to it? And the reason I call it "ethnic cleansing" is simply you've had far too many people saying out loud that it would be a good thing if there were fewer poor black people in New Orleans. You've had a Republican congressman say that, you've had Republican think-tank people saying this would be a good idea. And of course, it fully accords with the historic vision of the New Orleans police, which has been trying to accomplish this through urban renewal for the last 20 years. So until somebody can convince me that this isn't self-serving the industry of the Republican party, the Bush administration and the elites on the ground, I would defend calling it ethnic cleansing. What congressman said that? Richard Baker from Baton Rouge. He was the one who immediately spoke out and said, you know, that God has achieved what we were never able to achieve cleaning up the housing projects. As a Californian, how do you see our state shaping up in terms of potential disasters? Do you think local or state agencies here are in any better shape to coordinate then they were in Louisiana? Well, I mean, first you have to go back to the last major disaster, which was the Northridge earthquake, which revealed massive structural flaws in not only residential housing but, most importantly, hospitals. And the most dramatic revelation was that the welds in a lot of tall steel-frame buildings were bad. But the hospital association plus other interests banded together and basically shut down any debate on this. Tom Hayden very bravely tried to have a fundamental debate about earthquake safety and was cut off almost as soon as it began, and we're gonna pay a price for that. It means that a lot of the vulnerabilities that were exposed in the last big earthquake will kill people and lead to a lot of property damage in the next earthquake. Have you seen any improvement or reason for optimism? The one big improvement I see in California is actually what's happened in San Francisco. I encourage people to familiarize themselves with San Francisco's disaster planning. I could be wrong, but I think it's the only major city or locality in the country which really is involved in a grassroots dimension to disaster response. The problem with California and the rest of the country is that basically you're told to hoard toilet paper and water and then wait to be dug out of the rubble by experts. San Francisco has identified trained medical personnel, people with engineering and safety skills on a block-by-block basis. So they've created basically a grassroots network that can swing into action without having to wait for orders from the top down. San Francisco is probably the one city in the country where somebody will know where the old lady lives who needs her gas turned off or the person in the chair who needs to be moved to higher ground if there's a flood. And I think other localities and the state and the country as a whole need to embrace a kind of participatory model of disaster response, and provide the resources to make that kind of grassroots disaster response possible. And I'm not saying San Francisco is the perfect model, but it's in sharp contrast to the way the rest of the state is geared up. And basically you can just pick the name out of a hat: Will it be the Newport-Inglewood or the Hayward fault? Or will it be a new disastrous fire on the urban/wildlife interface? Who can tell? Except that it's inevitable and it will probably happen within 10 years. The phrase 'tipping point' has been coming up in a lot of your writing lately. Can you tell me why that is? Well, it seems everybody is writing about tipping points now in oil prices or the U.S. occupation of Iraq, but the sense in which I've used it is a bit different: I believe that there is increasing scientific evidence that we could reach—sooner rather than later—unpredictable thresholds in the environmental processes we've unleashed through the production of carbon dioxide, other greenhouse gases and changes in land use. I'm a member of the American Geophysical Union, which just cited a very important study in the recent issue of its newsletter. It shows a general circulation climate model, which is basically a super-computer model of the world's climate. And it shows an accelerating disappearance of Arctic sea ice, with the eventual result of really kicking the earth out of the climate state that it's been in since most of the Pleistocene [epoch]. And it raises the specter of runaway warming and consequences that I don't think are fully explored in the IPPC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change], the consensus scenario about global warming. And I use that just to illustrate the unpredictable or nonlinear aspects of climate and environmental—or for that matter, social—change. In other words, there are processes that act as accelerators, they even act as switches able to change from one state of the climate or landscape or vegetation, into an entirely different one, doing it at great speed. In past coverage of global warming, scientists who do and don't believe in it were presented as equals, even though the latter group is so small. Do you feel the media has been irresponsible in this regard? Well, sure, I mean the industry has spent a fortune creating almost artificial scientific dissent to challenge the consensus of global warming. The real debate I think is not whether global warming is taking place—or rather, the human and social role in it—but really whether the IPPC scenarios should include a more extreme maximum. In other words, I think there's a growing number of people who believe that the estimates of a 1 to 3 degree centigrade increase in global temperature over the next hundred years may be an underestimate. But that debate has been largely invisible, because the political foreground has been captured largely by paid so-called experts working on behalf of the oil industry and so on. Although, to be fair, there are a few major oil firms that seem now to fully accept that global warming is happening and that it's largely human-induced. Is that surprising to you? That they have come to accept that? No, I think it actually gives them a market advantage over some of their competitors. But if you look at the two most profitable industries in the world, which are the oil industry and the pharmaceutical industry, they're just literally awash in profits. Yet the pharmaceutical industry is abdicating research in basic drugs, antivirals, antibiotics, vaccine. And the oil industry is not even maintaining or rebuilding its traditional refinery capacity or infrastructure, you know, much less siphoning any of its profits for alternative forms of energy. So whatever your beliefs about peak oil, or the point at which oil prices begin to inexorably rise, whatever your beliefs about how grave the danger we face from re-emergent or new diseases, the point is that the earnings of these two most profitable industries on earth are not being invested in either new energy sources or in keeping up with the race that we're rapidly losing against the evolution of viruses and bacteria. And it's hard for me to think in my lifetime of more dramatic examples of where market mechanisms fail so completely to do what we're constantly told the market will always do, which is increase production and ultimately optimize human health and happiness. And I'm just sitting here reading the president's new pandemic plan for influenza, which gives everything to drug companies and almost nothing to local public health organizations. And it just epitomizes this problem. The free market doesn't necessarily profit from health and happiness. And meanwhile, the corporate offensive against the public sector has so discredited other alternatives that just nobody is willing to think outside the box. So you have the Democrats in Congress, for instance, going along with the Bush administration, trying to figure out how they can generate the maximum guarantees and inducements and subsidies to get the pharmaceutical industry to produce what are now life and death pharmaceuticals. Yet two generations ago, the U.S. government was actually in the business of making vaccines and pharmaceuticals. In fact, the flu vaccine was developed by Jonas Salk working for the U.S. Army. And nobody seems to be considering the possibility that, hey, maybe we need a federal biological arsenal, maybe the government, perhaps in conjunction with smaller startups and research intensive pharmaceutical companies, should be making this and providing lifeline medicine, just as a human right. Certainly the big drug companies have largely abandoned research. And the irony in all this is that they are extracting huge revenues from medicines, but most of the research is happening in public universities like mine, which then immediately gets turned over to little startup biotechs which develop the product, and then the big pharmaceutical companies acquire the license to manufacture it and they put all their money into advertising, not into research. What about Tamiflu? The Taiwanese were able to produce it very quickly, but manufacturer Roche argues that they produced only a small quantity of the vaccine and that a larger amount would take much longer. The administration has this kind of torturous plan to spend billions, but we wouldn't even see new Tamiflu in the stockpile for at least two years, until the summer of 2007 or later. Yet the Taiwanese showed that they were able to make it in 18 days. Roche has always insisted that this was an incredibly complex procedure, it takes years to do it, they're the only ones capable of doing it. The Taiwanese went in the laboratory and two weeks later they were making it. You know, if we wanted Tamiflu in the domestic stockpile in six months, we'd just go out and make it right now. It could be done. What can people in Santa Clara County do in terms of disaster preparedness? Well, first of all, they would greatly benefit from a quick study, which I assume you can do efficiently on the Internet, of disaster plans that involve citizen participation and mobilize citizen skills and initiative, and that use principals of neighborhood or social solidarity as the basis for disaster planning. The Japanese do this to some extent. The Cubans have a great experience in doing this throughout hurricanes; despite the image in the American press that it's all done top-down by the army, that's not how it works. I mean a lot of this in a way is common sense, but it changes your whole perception of your own situation, when you view yourself as a citizen with responsibility for your neighbors rather than as a selfish survivalist trying to hide out and escape the fate of other people. It also would drastically reduce the chance of panic, for instance, during something like avian flu. The Bush administration's approach is basically tell the state and the localities they have to come up with their own solution with minimal federal aid while they concentrate on giving a lot of money away to pharmaceutical companies. Most state plans, whether public health emergencies or natural disasters, tend to be these kind of elitist top-down plans and they're of course vulnerable. If one level fails, the whole system can break down. We saw the results of those two things combining in New Orleans—you know, federal neglect and inadequate top-down local planning. We saw the carnage created. But somewhere like your community, it seems to me, is an ideal place to begin to pioneer a kind of populace disaster response. What deeply impressed me being in Louisiana was just meeting ordinary people, you know, Cajun hunters and fishermen, that went in and rescued people in the city, with just minimal coordination by the state fisheries and wildlife department and people came up with really ingenious solutions. So I came away from New Orleans appalled by the negligence and failure of government, but kind of stirred by the American people's capacity to help each other. If a small progressive city or community really were to get it together and look at all the different models around the world for doing this and come up with its own model, I think it would be a tremendous demonstration. People need to feel that they're not just passive victims, that they have active roles as citizens for dealing with disasters.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the November 16-22, 2005 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.