![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

PerversionTherapy

When it comes to sexually violent predators, most Californians are content to lock 'em up and throw away the key. But San Jose's Dr. Stewart Nixon says he can fix the most reviled members of society, if the system would just give him the chance.

By Jim Rendon

WHEN Dr. Stewart Nixon works with his patients, there is one thing that never lets him down: rotting meat. It's the stench that Nixon uses, a pungent, nostril-enveloping smell that makes clients want to vomit. "Oh, it's the best," he assures me, calmly leaning back in his swiveling office chair. "It gets them every time." Rotting meat makes this round-faced, self-described Christian very happy.

Of course ammonia capsules are a little neater. He uses those, too, but rotting meat is like an old friend to the San Jose psychologist. And month-old steak is not the only trick up the shrink's sleeve--there's also video and audio tapes, role playing, mock dates, massage therapy, pornography, a machine that measures sexual arousal and a prescription of regular masturbation.

Nixon's San Jose office hangs like a museum display in a bare-bones, modernist building on The Alameda. The office's outside wall is a giant floor-to-ceiling pane of glass, giving the whole room the feeling of a cutaway model, the insides turned out for the world to see. In the room, two brown recliners face Nixon's desk and the swiveling chair from which he preaches his doctrine. In the midst of digging through his videotape collection, doling out stacks of research papers and running to find the video camera, Nixon manages to get his message across. He has found a way to heal.

If given the chance, Nixon says, he can fix society's most reviled criminals: priests with a taste for children; medical professionals with an eye for patients; people convicted of everything from child molestation and rape to exhibitionism. Not only can he quell their desire to rape or molest, but, Nixon says, he can focus them on socially acceptable desires. Nixon, with his bag of tricks, can rewire sex offenders' fantasies, snuffing out arousal to deviant imagery, building up their desire for consensual adult relationships and sex.

The result--sex offenders who become physically ill at the thought of molesting--is something straight out of A Clockwork Orange (although Nixon hates the comparison). Some clients vomit. Some just feel nauseated or get severe stomach pains. Others dream of throwing up when their subconscious allows them to indulge. "It's beautiful," Nixon exults. The more violent the reaction, the better.

But bile is not Nixon's only goal. Many of his patients have gone on to higher love: caring consensual relationships with adults. With years of work and regular follow-up, many of Nixon's patients have kicked their criminal urges.

"Sex abuse is learned behavior," asserts Nixon with broad confidence. "What is learned can be unlearned." Everything from sexual fixation to fear of flying can be dealt with by changing the brain's associations, he says. People associate a red light with stopping; they could just as easily associate a green one. Child molesting can be swapped for consensual adult relationships, if the treatment is right.

NIXON IS A true behaviorist, tracing his roots back to Ivan Pavlov and his famous dogs. Just after the turn of the century, Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, found that by ringing a bell every time he fed his dogs, he could eventually get the pooches to salivate just to the sound of a ringing bell. He had taught the dogs to associate the bell with food, shining light on a link between association and physical response. When Nixon got his degree from Standard in 1965, behaviorism was all the rage.

But the hook for Nixon was personal. Nixon was himself phobic--he had always been terrified of flying. "My hands would sweat just picking up the tickets," he recalls. After a few sessions where he was forced to visualize flights in a different way, he was cured. "Now I don't think twice about flying," he says. Twelve sessions banished a fear that seemed unshakable.

In the decades since, Nixon has taken Pavlov and his dog on a walk through a veritable red light district of human sexual behavior. He uses Pavlov's principles to unhinge his patient's sexual arousal from their deviant fantasies. Then, like a surgeon with a scalpel and thread, he reattaches the arousal to consensual adult fantasy. Fantasy, he says, is the key. "The amount of time people, even those with the healthiest sex lives, spend actually having sex is small," he says. But every 90 minutes people go through a cycle of sexual arousal. "There is a hell of a lot of fantasy going on out there."

Though recidivism rates are hotly debated, as well as the effectiveness of any kind of sex offender treatment, most studies show that at least 25 percent of untreated sex offenders are caught reoffending within a few years of release. Because studies rely on arrest records, and most sex crimes are unreported, many experts think recidivism is higher. Nixon thinks 50 percent is about right.

Treatment of any kind has been shown to have some positive effect. Studies that examine the effectiveness of Nixon's behavioral approach report recidivism rates between zero and 15 percent. That, along with the success Nixon has seen in his own practice, has convinced him that behavioral modification combined with more traditional talking therapy can break the cycle for society's most reviled criminals. He is not alone. Behavioral approaches have been used in Vermont, Washington state and in parts of Canada with some success.

But in California, only a tiny fraction of the state's sex offenders have the benefit of Nixon's approach. Sex offenders in this state and across the country have become pariahs--despised in both society and prison. Most serve lengthy prison terms with no access to treatment. Megan's Law, which allows for community notification, and California's new sexually violent predator law, which institutionalizes sex offenders after they have served their prison time, feed society's urge for retribution, but not the need to fix the problem. "We're into punishment," Nixon says. "Society doesn't care what works."

California's prison system lacks effective treatment programs, he points out, and just exacerbates the problem. Behind bars, where sex offenders are walking prey, offenders retreat to the only pleasurable thing they have left--their deviant fantasies. "They masturbate to their deviant fantasy for years," says Nixon. "Of course they reoffend when they get out."

Nixon is clear that he cannot treat everyone. He would gladly lock up and throw away the key on criminals who are beyond help and are not open to treatment. But the system as it stands now is horribly flawed. Studies estimate that one in four women and one in 10 men were molested as children. Close to a third of all women have been sexually abused at some time in their lives. California, he says, is asleep at the wheel.

INSIDE A COURTROOM on North First Street, Donald Robinson talks quickly in hushed tones with his attorney, then slouches down in his seat and looks ahead at the judge, then down at his feet. His close-shaved head is topped with a bald patch, and his sagging body is stuffed into a too-tight orange county jail uniform. Robinson has hit middle age behind bars, and although his prison sentence is up, it may be years before he will see the light of day again.

In 1995, Robinson was released from prison after serving 11 years for a double rape. After 10 months on parole without a hitch, Robinson missed a meeting and found himself back in the clink. When he was just days away from another release, something happened he couldn't believe. He was served papers and returned to the Santa Clara County jail to await another court proceeding. California's sexually violent predator law had just gone into effect, and Robinson was first in line to feel its wrath.

"Isn't this double jeopardy?" Robinson whispers to his attorney, somewhat sharply.

"The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law in a Kansas case," Robinson's public defender, Charlie Gillan, replies calmly and matter-of-factly.

"What about California?" Robinson says, tilting his head toward Gillan. His attorney explains that another case will be going to the California Supreme Court soon. But Robinson's years of legal challenges are over. It is time to face the judge.

Twenty-two years ago, Robinson broke into the home of a 71-year-old woman. Over the course of three hours, he held her captive and raped her repeatedly. Ten days later, Robinson broke into a nearby house, beating and raping a 25-year-old woman. When police arrived, Robinson was asleep in her bed--drunk.

He served five years.

In 1984, after his release from prison, Robinson drove a woman to an abandoned house. After she followed him into the garage, Robinson grabbed her, threatening to kill her if she resisted. He tore off her clothes and performed oral sex on her, then grabbed her head and tried to force her down on him. When she resisted, he pushed her to the ground and began to rape her.

All the attorneys present and even Judge LaDoris Cordell agree that Robinson is a bad man who did bad things. But Robinson is not on trial to fight this notion. In fact, he is not on trial for any of these crimes today. He has done his time for all of them and now is being judged for who he is, and who he might become. If he loses the case, Robinson will not go back to prison, but instead will be sent to a mental institution for treatment, possibly for the rest of his life.

Everyone agrees that Robinson's crimes fit the formulaic criteria of California's sexually violent predator law--he raped more than one person whom he didn't know. The case rests on the law's other two criteria: Does he have a mental disorder that makes him rape? Is he likely to do it again?

Most psychiatrists, when asked to evaluate whether someone will reoffend, play it safe. If he did it before, he'll do it again--that is the mantra.

When Charlie Gillan, Robinson's public defender, stands to make his argument, it is clear he is not going to roll over easily. "What is the percentage, the number, when you say he is likely to reoffend beyond a reasonable doubt?" he asks the judge. "Likely beyond a reasonable doubt," he repeats. Is that a 35 percent chance, 40? It must be less than 50, but how much less? With an inexact science like fortune telling, percentages are meaningless. There is silence on the bench as Cordell shuffles papers in Robinson's file.

Perhaps more important is the question of Robinson's mental illness. Is he mentally ill in a way that makes him rape? His attorney, Gillan, argues no. "He's a bad guy, not mentally ill," the attorney offers. He has burglarized, driven while drunk. He does lots of things besides rape, Gillan argues, in startling contrast to almost any criminal trial. Gillan knows that in a strange twist of forensic and political fate, a record of prior crimes could get his client released, while insanity will get him put away, possibly forever.

OF COURSE, Robinson had a miserable childhood. His mother was married several times. His biological father pimped out his mother and left the family when Robinson was young. One of Robinson's stepfathers beat him regularly, according to court records. When Robinson turned 14, his stepfather woke him up with a gun to his head and threw him out of the house. When he tried to return to visit his mother, she rejected him and his stepfather threatened to shoot him if he came back again. Robinson dropped out of school in ninth grade and rarely held a steady job. Later, when Robinson was married, he told psychiatrists that he suspected his wife was cheating on him. The marriage failed after a year.

Three psychiatrists interviewed Robinson, and he refused to talk to two of them. Nonetheless both of those managed to diagnose him as a paraphiliac--a rapist who is absorbed by violent sexual fantasies--a perfect fit for the sexually violent predator law, as paraphilia is considered a mental disorder.

The third doctor, who managed to get Robinson to talk, said he is not a paraphiliac. But he said that Robinson has a mixed personality disorder. He is impulsive, aggressive and a really bad drunk.

Without treatment, Dr. David Echeandia wrote, Robinson was likely to rape again.

And with that pronouncement, Robinson was put on a bus heading for the California State Mental Hospital at Atascadero. Two years from now he will be back in Judge Cordell's courtroom to go through the same process again. And he will return every two years until the law is changed, or a shrink testifies that he will not rape again, or he dies in custody.

TWENTY YEARS AGO, many sex offenders were sent straight to mental hospitals in lieu of prison, where they stayed for the duration of their sentence. Those who were sent to prison could be held as long as the state deemed necessary, and prison sentences in these kinds of convictions had the potential to be lifelong. But when California switched to determinate sentencing in 1977, offenders were simply released when their time was up. No matter how bad the behavior of the inmate, he could not be held past his release date. After too many ex-cons raped women or molested children, the Legislature took action. Under the guise of treatment, the Legislature passed the sexually violent predator law in 1995.

Many, including the American Psychiatric Association, claim that these laws warp the meaning of mental illness and are turning hospitals into human warehouses for people who don't belong there.

"These laws make a mental health issue out of criminal behavior," says Dr. Howard Zonana, a professor of psychiatry at Yale Medical School. Zonana chaired an American Psychiatric Association report on this kind of legislation that concluded these laws do little more than turn mental hospitals into very expensive prisons.

Defense attorneys claim their clients are being punished twice for the same crime. Others question whether these people can really ever be rehabilitated by the system anyway. California spends $100,000 a year treating each sexually violent predator (a total of $25 million a year and rising).

Meanwhile, in San Jose, Dr. Nixon says that for $6,000 a year, his own techniques could go a long way toward fixing these people. But for Robinson, Nixon and his rotten meat are not an option. Atascadero is where Robinson will likely spend the rest of his life, even though it seems obvious Atascadero doesn't want him either.

THREE HOURS SOUTH of San Jose, Atascadero State Mental Hospital sits in a rural valley surrounded by steep low hills. More than 250 sex offenders are housed here--130, like Robinson, have been committed; another 120 are just killing time, watching television, going to the music room or the arts and crafts room, waiting for their court date. All of Atascadero's 1,000 patients have some criminal background--some are referred by the prison system, others are not competent to stand trial, others have been found not guilty by reason of insanity. The majority of this population suffers severe mental disorders like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Others are mentally retarded.

The predators like Robinson stick out because, for the most part, they do not suffer from mental illness. The rapists and child molesters who walk the halls in the standard-issue khaki attire are a different breed, a group who would never be here without the state's dramatic alteration of the criteria for admission.

Carla Jacobs, a board member of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill, a national mental health advocacy group, is outraged that these sex offenders are housed with mentally ill patients. "I have no problem with keeping sex offenders off the street. I do have a problem when the state confuses them with people that have a mental illness," she says.

"There is no mental disorder that is related to rape," confirms forensic psychiatrist Jules Burstein. "It's like trying to find a mental disorder for a guy that holds up liquor stores. As soon as sex is involved, we say he must be sick. There are a lot of crimes you have to be crazy to commit, but we don't institutionalize those people," he says.

There is no doubt, even in the mind of the man who runs the sexually violent predator program at Atascadero, that this population is different. They are not mentally ill, says Craig Nelson, clinical administrator at Atascadero. "They have a psychological disorder," he says. "They have sexual desires that most of society condemns. Something has gone wrong."

The sexually violent predators have posed a challenge for the mental hospital. These patients think they have been wronged by an unconstitutional law. Many of them have been advised by their attorneys not to participate in treatment. Some try to sabotage group sessions. They file complaints about everything. One man even complained that the nurses were not good-looking enough to change his sexual focus. And fights break out.

Atascadero's treatment for these patients is mostly focused on self-examination. Inmates are told to write accounts of their crimes and try to determine what led them to victimize and what clues to look for in their behavior that will likely lead to raping or molesting, like getting drunk or hanging out at ice cream stands. They learn to empathize with their victims, writing mock letters of apology. All of this, especially understanding cues that may lead to deviant behavior, is reinforced in the final treatment stage.

But only a fraction of inmates, Nelson reports, are participating in any meaningful way. Most of the 250 patients in the program are in the first phase, which is really just an informational session about the law and the program.

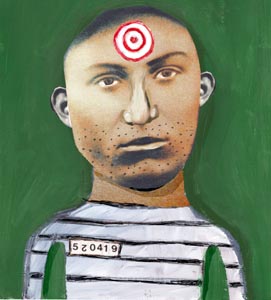

Pariah Heap: California's sexually violent predator law has led to more offenders being dumped at Atascadero State Mental Hospital despite experts' assertions that they are not mentally ill.

IN A SMALL ROOM reserved for substance-abuse classes, two hospital patients sit behind a wooden table. Their psychiatrist, Gabrielle Palladino, has refused to tell me their names or even their county, citing privacy concerns. Yet in a strange paradox, every word these men utter in the most private therapy session can be used against them in court.

Both men wear the khaki shirts and pants that all inmates are issued in the hospital. The man sitting closest to me blushes when he talks. Though his large hands are steady, his nose quivers slightly, betraying his nerves.

"I realized I have been a screw-up most of my life," he says in a surprisingly quiet voice. "Every time I was busted and went to jail, I said I would change. I was just kidding myself." Atascadero, he says, has helped him in a way prison never could.

In group therapy, he discovered the things he has in common with other offenders. "A lot of us had abusive parents, we used drugs and alcohol, we were sexually abused as kids." He pauses for a moment. "It is not an excuse," he says. "People have been through that and not offended. What makes us different?" he asks rhetorically. Indeed, it's a question no one can answer.

In the time he has been here, he has learned to pick out the things that lead him to rape, like drugs and picking up prostitutes. Just as important, he says, is for him to monitor what is going on emotionally. "If I get a case of the fuck-its, that is high risk. I felt like that all the time in prison."

Next to him is a smaller man with a beard and glasses. He is a fast talker with a rare kind of charisma. He is the kind of guy you want to go have a beer with just to hear him spin a tale. He is a convicted child molester.

"Before my offense I knew I was going downhill," he says. "But there was no place to go. I was married with three kids. If you're a drug user or a gambler, there are programs. If you are a sex abuser, you can't just walk in off the street."

Both men spent years in prison before they got here, and neither man got treatment there. Of Palladino's 100 patients, only one said he enrolled in a treatment plan in prison. "There are three things that can get you killed in prison," says Palladino, a former prison psychiatrist, "owing money, snitching and being a sex offender." Just getting these men to admit their crimes is a huge accomplishment, she says.

But this accomplishment has not been achieved with the bearded child molester. Since 1996, he says, he has been waiting for the law to be cleared up. The bearded man's attorney told him not to talk about his crimes, so he has not been involved in treatment, despite the fact that he lives in a mental hospital. The biggest problem with treatment at Atascadero, he says, is the total lack of confidentiality.

"I look forward to getting out and going to a group where I can be free in what I say," he says with certainty that he will be freed soon. March or April at the latest, he says. But so far, only one person in three years has been released from the sexually violent predator program. Few are far along in treatment.

Plans are in the works for expanding Atascadero and eventually building an entirely new hospital just for sexually violent predators, a population that Dr. Nelson thinks will top out at 1,500. Not because the problem will be fixed, but because the state will keep them in prison. With three strikes legislation and increasing penalties across the board, multiple sex offenders, he says, will grow very old behind bars.

ALTHOUGH ATASCADERO'S program pushes inmates toward the kind of self-examination that would probably be good for every criminal, it does not get at the root of the problem, critics say. "What you end up with are insightful child molesters," says Pat McAndrews, who works with Dr. Nixon. It doesn't change behavior.

"Sex is nonverbal," Nixon adds. "People don't think through the consequences carefully--just look at President Clinton," he says with a laugh. Sex is not reasonable, and it needs an approach outside of reason to be effective.

Craig Nelson at Atascadero believes that he can teach some sex offenders not to act on their deviant fantasies, but he concedes that the fantasies of rape and child molestation will never change.

Nixon, on the other hand, is certain he can subdue the fantasy and, more importantly, strip it of its erotic significance. Without the erotic fantasy, there is no need to molest or rape. Kill the fantasy, he says, and you've licked the problem.

Sitting forward in Nixon's brown chair, Tom, a patient, holds his hands together as he talks, sometimes rubbing a finger, sometimes brushing his own leg or holding his knee. Tom was convicted of molesting 10 women, including a 13- and a 15-year-old girl in his office.

"This was my dirty, awful secret," Tom says with the easy pace of someone who is used to talking about painful events, but also with the gravity of a person who understands that he has made horrible mistakes. "I will always have to make up for my offense," he says. Since his arrest, Tom says he has not committed any more crimes, and credits Nixon with curing him of his urge to touch women.

"I used to look at women," Tom says. "I would look and look and then touch them." After a few years of treatment, he says, he would still look, but stopped himself from grabbing them. Nonetheless, the fantasy was still alive. Now, after six years with Nixon, he says that he just does not pay attention. The fantasy that drove his sexual arousal is gone.

Nixon's central piece of technology sits on an end table between the two chairs. The penile plethysmograph looks more like an overblown clock radio with a calculator tape rolling out of the top than a cutting-edge psychiatric device. This unlikely gadget allows Nixon to determine just how aroused his patients are by certain stimuli, a crucial component of his work.

Nixon reaches in the drawer and pulls out a cable with a small loop at one end. "This little hoop is it," he says as he pulls the loop wider and smaller with his finger. The hoop fits around the sex offender's penis and the other end plugs in to the machine. Once the patient is rigged, Nixon asks the patient to recount a deviant fantasy, one involving exposing himself or rape or child molestation, whatever the patient's preference. As the patient talks through the incident, Nixon monitors the arousal levels.

"While you're talking, you try to feel as aroused as you can, you have to," Tom says. When Tom talked to Nixon, he would imagine himself there in his office with the girl. "When I reach for her leg, I imagine that she reaches for my leg, too."

Then comes the rotting meat, sometimes an ammonia capsule--a nauseating jolt that stops the fantasy dead in its tracks.

The foul smell helps to break the erotic association with the aberrant fantasy. The routine is repeated and repeated, sometimes for years, until the patient no longer gets an erection from deviant fantasies.

Patients like Tom are also required to make audiotapes describing every detail of their crimes. While putting a tape together, offenders cannot allow themselves to become aroused by the memories. Masturbation beforehand is encouraged.

"I'd masturbate two or three times and then do the tape," Tom says. "Sometimes I'd still get aroused. I'd have to stop and masturbate again and then go back to doing the tape." Arousal and masturbation to legal adult fantasies is encouraged by Nixon and is an integral part of his therapy.

Once the tape is complete, the client listens to it over and over, but never before masturbating to the point of exhaustion to legal, consensual material. That way Nixon builds up erotic associations with positive scenarios while making the aberrant imagery sexually boring.

Sometimes child molesters are encouraged to molest a mannequin while they are being videotaped. While molesting they talk about what the "child" is thinking. Usually they voice their own rationalizations--the child liked it, it didn't hurt them. Then the offender watches the video with Nixon, who helps them deconstruct their own lies.

Throughout the therapy, Nixon also teaches his clients social skills--how to interact with adults, especially those of the opposite sex. McAndrews often goes on mock dates with offenders. At the top of the list is teaching these people that rejection is OK. Nixon role-plays women turning down his clients for dates, sometimes in the most cruel way possible, to help them confront their fear. Many offenders only know violent and sexual ways of touching. Massage therapy helps to broaden his clients' understanding of physical contact. There are also group therapy sessions where offenders talk about their problems.

It is a long process, says Nixon; two years is the minimum, with indefinite follow-up.

"It can never end," Tom says. "You want to file it at the back of your head, but you need to keep it at the front half of your brain," he says, touching his forehead. "If you put it at the back and forget about it, you will do it again."

Like many sex offenders, Tom was molested as a child. When Tom was only 91/2 the priest in his small town in Mexico began molesting and raping him. It went on until Tom was 11.

"I remember how bad my hands smelled after having sperm from another man on my hands or in my body," he says. "It screwed up my life. I never felt good enough for anything. It broke my soul."

But he doesn't use the experience as an excuse for what he did. Lots of people are molested and don't continue the cycle. But this early violation did a lot to shape Tom's understanding of sex in a way that made it much easier for him to offend. "I thought I had permission to touch people," he says. "I thought it was natural."

MOST SEX OFFENDERS, Nixon says, have experienced some major childhood trauma, sometimes molestation, but not always. What results is an inability to relate well with adults, miserable social skills and a very narrow understanding of sexuality, touch and interaction in a relationship. These people, he says, are afraid of adult relationships. Nixon wants to fix that.

Leaning forward, gesturing with his hands, Nixon's voice rises when he talks about the big picture, about the religious community's utter failure to deal with human sexuality, the Puritan values that keep sex a taboo subject for discussion, even among lifelong couples. "Why not teach healthy sexual thoughts?" Nixon asks. Why not teach children how totally different boys are from girls? Why not drag it all up from the basement?

The faces that come through Nixon's door show him a range of problems caused by society's inability to accept the sexual side of human nature. From the priest who molests children because it is easier to molest than to admit being gay, to the rapist who simply cannot understand why he does what he does, there are too many problems shoved under the rug, problems punished with a slap that are sure to be repeated. There are so many more problems that Nixon wants to get his hands on, because he can do some good. "I'm not making a lot of money," he confides, adding that these people make up only half of his caseload. "But I feel like I'm doing something worthwhile."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Illustration by Katherine Streeter

Christopher Gardner

From the November 19-24, 1998 issue of Metro.