Eros & Agape

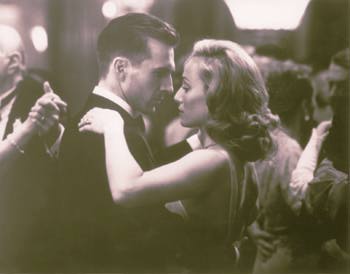

Love in the Burning Zone: Ralph Fiennes and Kristin Scott Thomas smolder in Anthony Minghella's "The English Patient."

'The English Patient' and 'Breaking the Waves' find romance in extreme sacrifice

By Richard von Busack

THE LOVE STORIES of the end of this century have turned morbid. In two prestigious new films, heroines die exotic deaths for the sake of love. The sensibilities of directors Lars Von Trier and Anthony Minghella--Lutheran and vaguely Catholic, respectively--diverge. And yet, the themes of Oscar bait The English Patient and Cannes Grand Jury Prize-winner Breaking the Waves are similar.

Both posit existential romances in which malignant fates wait for lovers; both are set in the traditional background of nature at its wildest. We're taken to the North Sea Scottish coast in Breaking the Waves and to a desert redder than Antonioni's in The English Patient. Lastly, both are romances for the moribund: a wife tending a quadriplegic husband in Breaking the Waves, a nurse caring for a burn victim in The English Patient.

Of the two, Breaking the Waves proves much more successful at impassioning an audience, thanks to Emily Watson's seemingly artless performance as the wife. Breaking the Waves also has the advantage over The English Patient (based on the book by Michael Ondaatje) of not trying to shape itself from a novel that seems almost unfilmable.

"Eschew the monumental. Shun the Epic. All the guys who can paint great big pictures can paint great small ones." Ernest Hemingway's cranky advice could apply to Minghella, whose great small picture Truly Madly Deeply (1991) said something both intelligent and subversive about the fleeting nature of romantic love. The English Patient loses its way trying to touch all of the corners of a novel that was simultaneously expansive and compact; the adaptation has been changed drastically to put the focus on the second half of the book.

Italy in 1945: In a ruined villa, a Canadian nurse, Hana (Juliette Binoche), stays in Europe to nurse her own numbness at what she's seen in the war. She has but one patient now, for whom she feels a tender but almost-abstract love. He is the severely burned pilot Almásy (Ralph Fiennes)--the living cinders after an affair is over. His own tale is told elliptically, in flashback. He was a desert explorer who, very much against his will, became the lover of Katharine (Kristin Scott Thomas), the wife of a friend.

Heavily flashbacked, The English Patient's front doesn't match its back. The shift from Bedouin camps to the prewar pomp of Shepheard's famous hotel in Cairo to an Italian villa could only be held together by a first-rate performance. In the 1945 sequences, Fiennes is bedridden and swathed in latex. In his past adventures, he is supposedly in love with the desert, but he gazes at it haughtily, unhappily, as if he deplored every grain of sand in it. Scott Thomas, as Almásy's doomed lover, is suffused with her usual hollow-eyed grace. She is one of the few actresses who radiate intelligence and sophistication the way that baser thespians just radiate sex.

Her intelligence is a downfall, though; Scott Thomas seems too cerebral to have her life ruined by a grand passion or to inspire sentiments such as "The heart is an organ of fire." And Binoche's Hana is an unplayable character, a construct of the soul in mourning. The miscasting continues unabated. Hana's sort-of uncle turns up mysteriously at the villa. Caravaggio is his name, like the artist; but unlike the book's romantic thief, he appears here in the form of Willem Dafoe, a grimy jackal on the road to devolving into Steve Buscemi.

For a playwright turned movie director, Minghella has developed a strong visual sense. In the crash in which the English patient loses his face, the pilot is silhouetted against cream-colored flames. Like Ondaatje, Minghella succeeds in taking the agony out of the burning, to make the fire a nimbus, a halo. In another remarkable scene, Minghella depicts the inside of a chapel, still sandbagged from bombing. Hana is hoisted up on ropes for the better look at a fresco; weightless, she swings and explores the walls by the light of a flare, like a spelunker.

Minghella's telling of how Caravaggio himself was wounded, however, takes the form of an appalling spurt of violence that serves no real purpose--a shock meant to convince you that what you're watching isn't just melodrama. As anyone can tell you who saw The Last Temptation of Christ, nobody endures torture as noisily as Dafoe. His ordeal, in a movie being sold with Ralph of Arabia on the poster and some vaguely comforting words about how love always endures, will be an unpleasant surprise for some audiences.

Sex and Salvation

'BREAKING the Waves" places even more extreme demands on its heroine. Bess (Watson) inhabits a tiny, remote Scottish town that has taken religious guilt to a parodistic extreme. Women are excluded from speaking in church; the elders of the clergy have even disposed of the bell from the church tower as a worldly frippery.

Bess must face the patriarchs in preparation for her upcoming marriage. She's asked, what good have the Outsiders have ever brought? "Their music?" she answers, which bodes badly for her relations with the church. Rock music divides Breaking the Waves into chapters to frame the story--Jethro Tull and Procol Harum heard over the radio being something like otherworldly voices to a girl in this far country.

Bess is a village girl, touched in the head--a cleaning woman who hears God speaking to her. She marries Jan (Stellan Skarsgard), an offshore oil worker whom, we suspect, she knows not too well. Marital love is a discovery that makes her nearly half mad; when Jan returns to the oil platform, Bess must be physically dragged off of his helicopter as she tries to follow him.

Never having read the short story "The Monkey's Paw," Bess pleads with God to bring back her man. He does, as a quadriplegic, after an accident on the rig. During his recovery, Jan first asks, then demands, that his wife tryst with other men and bring the stories back to his bed. Despite her nausea at the idea, she complies. Bess eventually sacrifices herself, since, like so many of us, she has agape (love of God) and eros (love of sex) irretrievably confused in her mind.

Breaking the Waves is a lugubrious tale, when summed up in short; the distressing ending should make more than a few women furious. But Watson is a raw and convincing performer, and the film isn't meant as an erotic tale, as a postmodern Lady Chatterly's Lover (Lord Chatterly was a paraplegic himself). Bess doesn't have a Mellors to give herself to; the men she accosts are uniformly unappetizing. The tale-telling is detached, cool; the "eye of God" view Von Trier takes contrasts with the fervidness of Watson's Bess.

If Breaking the Waves had been less ambiguous, Bess would have been the lone voice of purity, akin to André Gide's little blind girl in The Pastoral Symphony, who sees more than those of us with sight. But Bess is not only an innocent but unexpectedly lewd, and her burr of an accent caresses. The honeymoon is the erotic part of the tale. Fully clothed, Bess examines Jan; it's the first time she's seen a naked man. She blows a strand of hair out of her eyes to have a better look at the her husband, or rather the part of him she calls--with the catch in her voice of a good girl using a very dirty word--"prrrrick."

Jan is opposed by a skeptic who isn't just a prude, but who may be absolutely right. Dodo, Bess' sister-in-law, is played by lean, spiky Katrin Cartlidge. Dodo punctuates Bess' plan by pointing out to her, rationally enough, that Jan's voyeuristic scheme is the result of a scarred brain and lots of pain-killers. Von Trier has it both ways, offering an celestial conclusion that seems like the nailed-on happy ending of the old days--unconvincing and, like so much of the film, simultaneously detached and moving.

This peculiar but inspired film shows that Von Trier is loosening up. He was at first an overpraised technician. Indeed, Breaking the Waves is handsomely shot in wide screen by Robby Müller, who conjures up a strange, almost extraterrestrial landscape, turned by tinting into opalescent skies and black seas.

After Von Trier's boring Zentropa and his discursive but funny The Hospital, he's at last showing those qualities many have claimed of him already: the potential to be a profound filmmaker. Like Minghella, Von Trier has taken on an important topic--of the notions of God and love in skeptical times--and like Minghella, he's treated the theme with almost exotic suffering. What will these insane tales look like in a saner time? I say that without much hope that there will be such a thing as a saner time.

Breaking the Waves (R; 159 min.), directed and written by Lars Von Trier, photographed by Robby Müller and starring Emily Watson.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Phil Bray

Not Your Father's Lady Chatterly: Emily Watson commits adultery to please her husband in "Breaking the Waves."

The English Patient (R; 161 min.), directed and written by Anthony Minghella, based on the novel by Michael Ondaatje, photographed by John Seale and starring Ralph Fiennes and Kristin Scott Thomas.

From the November 21-27, 1996 issue of Metro

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)