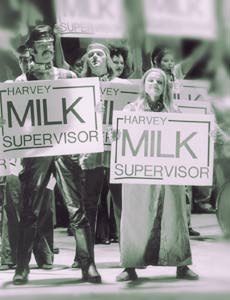

Musical Protest: Gay activists march in "Harvey Milk."

Photo by Marty Sohl

San Francisco Opera brings stirring and relevant 'Harvey Milk' home

By Philip Collins

IT WAS 18 years ago that San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone were fatally gunned down by Dan White, the ex-policeman who only days before had announced his resignation from the board of supervisors. Infuriated by the rising tide of gay activism that was taking hold in his beloved city under Milk's advocacy--the first openly gay elected official in San Francisco history--White felt it necessary to take the law into his own hands.

Seeing San Francisco Opera's West Coast premiere of Stewart Wallace's and Michael Korie's opera Harvey Milk at the Orpheum Theatre Saturday night, one couldn't help but feel stricken by the impact of these events, the up-to-the-minute relevance of the gay community's ongoing struggle for acceptance versus the dogged opposition of America's most conservative religious factions. Seeing it played out here in San Francisco, on the home field, so to speak (after its previous premieres in Texas and New York), it's easy to appreciate how intrinsic this story is to the Bay Area's history.

Harvey Milk is a spectacular theatrical accomplishment in many respects. Wallace's and Korie's translation of the story's epic subject matter to the stage is carried off with integrity and a great deal of imagination. Tragic as the story is, Korie inserts a good deal of humor that plays off the work's serious tone to great effect.

Christopher Alden's ingeniously fluid staging is so integral to the work's success that his name should be emblazoned alongside the composer's and librettist's. Heather Carson's lighting and the austere set creations of Paul Steinberg contribute to the work's gripping visual impact in no small way.

Korie's adaptation encompasses Milk's life, from adolescence to death at age 48, including his discovery and eventual open admission of sexual orientation, telescoped against the huge backdrop of San Francisco's fomenting gay movement. Korie finesses intersections between personal and societal levels ingeniously, distilling both histories via key events with an economy of language and crafty interlopings of ritualized drama and realism. What absence there is of prosody in Korie's lyrics he makes up for with wit and succinctness.

The opera takes place in three acts that divide Milk's life in distinct stages. In the first act, we see a 15-year-old boy setting off for an afternoon of opera at the New York Metropolitan. His mother warns him to avoid strange men, and once there, young Harvey voices his bewilderment in song about "the men with no wives," men who memorize librettos rather than football scores.

His curiosity leads him to Central Park, where he is entrapped and handcuffed by a plainclothes policeman. The handcuffs remain in the following scene, as Milk, a Wall Street stockbroker, finds bodily refreshment, though confinement, as a closet gay. His taking up with a gay street activist, Scott Smith, and the legendary Stonewall Uprising of 1969 inspire him to come out. Of course, the handcuffs snap off.

Act II shifts to San Francisco's Castro district, where Milk and Smith open a camera store. He grows a ponytail and makes several unsuccessful bids at running for supervisor, finally winning, after cutting the locks and donning a suit. The first Gay Pride Parade concludes the act in full regalia.

The third act takes place at city hall, where politicking among the newly elected, racially diverse board is in full swing. Brooding Supervisor Dan White is the lone exception, grumbling at his desk with a chocolate donut in hand, unabashedly repelled by his colleagues' alliance with Milk. Following his resignation and failed attempt at reversal, White takes out his pistol and finishes off Milk and Moscone. The opera concludes with the historic candlelight vigil, observed by Milk's spirit.

WALLACE'S MUSIC is, much of the time, compelling and resourcefully textured. His score keeps things moving at an engaging clip, enlivening potentially static office scenes with varied instrumental figures while delineating San Francisco's cultural make-up with strategically applied stylistic contrasts. Ravishing arias and some decent (and indecent) choruses crop up throughout--some real lemons, too, but Wallace excels where it counts. Still, a fine should be levied for the outright pilfering of Stravinsky's Rites of Spring ("Dance of the Earth" episode) in the second act.

The score benefits from terrific performances. Music Director Donald Runnicles pulls vibrant playing from the pit, and the cast is ingratiatingly well-voiced; although their attempts at dance are abominable.

Robert Orth, in the title role, is crisp and radiant, while tenor Bradley Williams, as Milk's companion Scott, is unduly challenged by the role's upper tessitura. As Dan White, Raymond Very is heartwarming--believe it or not--lamenting how his neighborhood's gone to ruin. Adam Jacobs turns in a fetching performance as young Harvey.

Among the many who play multiple roles, counter-tenor Randall Wong shines as harbinger to the candlelight vigil, with his intoning of "a quiet descended upon the city." Although the choral epilogue that follows falls short of its promise as the opera's denouement, Harvey Milk is a vital, highly entertaining work, and its content is certainly germane to our times.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Stage]](/stage/gifs/stage468.gif)