![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

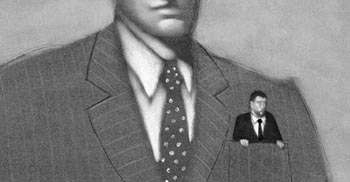

Illustration by Katherine Streeter But I'm a Queer Leader A Bay Area program to reverse sexual orientation boasts a 50 percent 'success rate.' But at what price heterosexuality? By Michelle Goldberg TWENTY-ONE-YEAR-OLD KYLE FRIESEN is gay and doesn't want to be. A handsome former hairdresser from Winnipeg, Canada, with a goatee, hipster sideburns and dark, gelled, tousled hair, he doesn't look much different from any of the insouciantly out-of-the-closet young men one sees strutting through San Francisco's Castro district or New York's Chelsea. He favors dark jeans or cargo pants with big, chunky boots, and he's adorned with five piercings--a ring in his eyebrow and inner left ear, a hoop in each lobe and a stud in his upper right ear. He hates camping and loves fashion--his favorite magazine is 'InStyle'--and dancing. But he's put all that aside this year, instead devoting his whole soul to one excruciatingly difficult goal. He's trying to become straight. That's why in January, having made up his mind to change his sexual orientation, Friesen moved into an apartment complex in San Rafael, Calif.--about 45 miles north of San Francisco--along with 20 other Christian men attempting to "walk out of" homosexuality. All were part of a one-year live-in program called New Hope, run by Frank Worthen--one of the founders of the ex-gay movement--and his wife, Anita. Among those who entered with Friesen were a singer who used to tour with Jerry Falwell's choir, a recent Yale theology graduate, and an articulate 23-year-old former actor who had a full-scale Messiah-complex nervous breakdown while studying in Jerusalem. As of August, 18 of the original 21 who entered with Friesen remained. Friesen had blamed much of his homosexuality on a desperate need to be accepted. Now New Hope's residents and staff--all of whom have been through the program--have become like a family to him. As soon as he arrived, he said, "I felt good. It's been amazingly affirming from my peers as well as from the older men that are there. I'm a people person, so it's nice to be able to come home from work to a group of a people." He'd been isolated at home, insecure and miserable about his inability to relate to other boys. At New Hope, he got to feel like he was one of the guys. The men at New Hope eat dinner together every night--they take turns cooking. They go on outings--baseball games, trips to San Francisco's Fisherman's Wharf, retreats in Yosemite National Park. They take volleyball lessons from an ex-gay coach. They watch movies together and have long, intense talks. If nothing else, the program certainly seems like a temporary cure for loneliness. ALTHOUGH THE ex-gay movement--a network of individuals and groups dedicated to overcoming homosexuality--is dominated by men in their 30s and 40s, there are a significant number of people in their late teens and 20s joining it. Friesen is the youngest person at New Hope, but there are also two 23-year-olds and another 21-year-old who started in September. At Exodus 2000, a conference all the New Hope men attended in August that brought over 1,000 ex-gays and their families to San Diego, kids with bleach jobs and baggy jeans who wouldn't have looked out of place at a Limp Bizkit show milled about. Many wore T-shirts advertising Christian rock bands or proclaiming attitudinal slogans like "Satan is a Punk." It was hard to turn around without meeting someone like 20-year-old Gary Fletcher, whose mother drove him to San Diego from the small town of Fontana, Calif. Gary recalled a night, months ago, when he was dismissively dropped off on a street in West Hollywood by a married man whom he'd just slept with. He said he lay down on the pavement sobbing and saying, "Jesus, either you take my homosexuality away from me or I'm going to take my life away from you." The conference, said Gary, was the happiest five days of his life, the first time he ever felt truly relaxed and at home. For Friesen, the experience was similar. "The Exodus conference was, like, the first time in my life I've hung around guys my age who are dealing with this, 'cause all my friends back home are straight," he enthused. For young Christians struggling with their homosexuality, the ex-gay movement offers the same kind of instant community that homosocial centers like the Castro in San Francisco do for other gay kids. And because many of the problems that the ex-gay movement insists are endemic to gay life--problems like loneliness, alienation and low self-esteem--are also common to young people generally, the movement seems to offer its yearning believers a solution to all life's ills. FROM THE MOMENT he became aware of his attractions to men, Friesen wished they would go away. When, at 16, he came out to his friends, it was not at all triumphal. "When I told my friends, I wasn't like, 'I'm here, I'm queer.' It was more 'I'm having these feelings and I don't know what to do. I want to change. I don't want to be this way.'" Still, he had a secret boyfriend for five years, from 13 to 17--a boy who stayed in the closet and recently married. At 18, Friesen said, he started going to gay clubs with his straight girlfriends and doing "all kinds" of drugs. But he felt guilty and sinful. "Do gay people go to hell? I don't know," he said. But he found that uncertainty terrifying. Besides, he said, without God as he conceives Him in his life, "I can't be fulfilled." He believes he can't be gay and whole. New Hope's live-in program, one of four residential ex-gay ministries for men in the country (the others are in Tennessee, Kansas and Kentucky), is run as an intensive rehab and costs $800 a month. Founder Frank Worthen aims to impart "both a Christian religious view of things and also a bit of reparative therapy," he says--although neither he nor anyone on the program's staff has any psychological training. "It's a psychological program that gives you the understanding of how homosexuality began in the first place from deficits in your life that have to be filled before you can emerge out of that lifestyle." In ex-gay ideology, homosexuality is a form of "sexual brokenness" that results from early deprivations. Usually it's attributed to the absence of a loving father, except when the homosexual in question had a loving father, in which case it is blamed on peer rejection, an overbearing mother, sexual molestation or whatever factors fit (Friesen, for example, has an excellent relationship with his father). "Usually homosexuality is what they call a father replacement search. It's to find a loving, approving male that will affirm you," Worthen says. Like almost everyone in the ex-gay subculture, he believes that gay relationships simply can't work, a view he bases on his own experiences and those of the men who come to him. All his relationships were "very bad," he says. "Anonymous sex is about all that's there, really. Most of the times when you get into a relationship, you get burned. They can't meet your needs." IF YOU'RE AN educated, moderately liberal valley dweller, you're probably sneering by now. You may have even seen the movie But I'm a Cheerleader, with RuPaul and Natasha Lyonne, which broadly satirized ex-gay camps for teenagers (which, by the way, don't exist). Try to imagine, though, what you would do if your passions conflicted so totally with your most unshakable gut beliefs that you truly felt following your libido would lead you to perdition. Leviticus 18:22 says, "You shall not lie with a male as one lies with a female; it is an abomination." Friesen, like most of the residents at New Hope, takes that line literally. His parents are deacons in their church, and he was raised an evangelical Christian. His religion is as deep in him as his sexual orientation. His conflict is unresolvable. We've all heard the statistics about depression among gay kids--according to a study reported in the AMA Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, "Gay, lesbian, bisexual, or not sure youth report a significantly increased frequency of suicide attempts. Sexual orientation has an independent association with suicide attempts for males." Growing up gay isn't easy for anyone, and plenty of gay teenagers wish they could just be "normal." The gay community tells Friesen that he was born gay, that it's an unalterable part of him. It's the last thing he wants to hear. "The pro-gay movement is so pushy," he complains. "It's like, 'You're gay, accept it, love it.' They don't give people a choice." The ex-gay movement offers Friesen at least the illusion of options. Frank Worthen's ministry tells him he can have a life like his parents and married sisters back home in Winnipeg--that he can have a wife, children and the place in the world that he dreams of for himself. And that's what Friesen wants--not celibacy, but family. His dreams of marriage are one reason why he's "committed to this whole change. Because it's hard--I'll tell you it's hard," he says definitely. "That's the bottom line. This has definitely been the hardest year of my life. There are times when I hate my life." Friesen is too self-aware to expect that he'll magically become straight when his time in the program runs out this winter. "I don't think I'll ever lust after girls," he says. "Lustwise, I think it will always be guys. Just like any sin, Satan's going to bring temptation. As you continue your relationship with God, you learn to fight those temptations. I believe it will almost get to the point where it's like I don't have these feelings." But after his time at New Hope, he insists he can feel himself changing. "I've already noticed the difference. With my straight girlfriends, I'm not necessarily completely physically turned on by them, but once I get to know them at a deeper level I become physically attracted to some of them. It's like, whoa, there's something more here." THE COMPLEX WHERE New Hope residents occupy five apartments is a low, boxy building a few blocks from the brewpubs and upscale California-cuisine restaurants of San Rafael's tiny downtown. The doors face away from the street, and a long balcony filled with leafy plants and cacti stretches in front of them. Except for the bedrooms, which are private, New Hope's 18 residents can come and go among the apartments as they please. The units are large and light-filled, decorated in mauves, grays and beiges. There's a lovely grandfather clock in one of the living rooms, and hanging plants throughout. Wind chimes sound faintly outside. Walls are adorned with posters of howling coyotes and paintings of desert scenes. Were it not for the huge tapestry of the pietà in one room or the framed Bible quotations scattered everywhere, the dwellings would look like upscale Santa Fe hotel rooms. There are bunk beds in the bedroom Friesen shares with a shy man in his early 30s, a room wallpapered with letters Friesen's received from his friends and family, as well as old photographs, one showing him as a bleached blond. His small CD collection is filled with Christian records of mainstream pop--there's an album by a group called Out of Eden, whom Friesen describes as a Christian Destiny's Child, and a few from The World Wide Message Tribe, who make Christian techno. Looking at them, he says he misses going out dancing. "There was a time when my friend and I would go to this club and just dance the whole night," he says. "Sometimes I just dance in my room." One August evening it was Friesen's turn to cook. He was given $30 to buy food, and because he's graduated to Phase 3 of New Hope's program, he was allowed to go shopping at Safeway alone. He returned with canned corn, mashed potatoes, ham steaks, turkey ham steaks, and gravy. As he prepared dinner, residents home from work milled around on the balcony or lounged on couches inside the apartments. Most were startlingly friendly. Before eating, they all held hands and Friesen led a prayer, politely thanking God for my presence. Then they took their seats around a large oval table and bade me to serve myself first. A jovial, flush-faced man with sun-creased skin, sitting at the far end of the table, turned toward me and said, "You realize that this is a process and you're just seeing the beginning." In response, I asked everyone where they saw themselves in 10 years. "In 10 years I'll be sitting at the dinner table with my wife and kids," responded a chubby man with wire-rim glasses. Pointing to the man next to him, he added, "I'll be waiting to go to his wedding." To which the other man responded with a distinctly queeny inflection, "Oh puh-lease, I'll be married way before you." The chubby man rolled his eyes and told me, "We're very competitive."

NEW HOPE PARTICIPANTS are expected to work full-time jobs in the surrounding community, but they all have to be home by 5:30pm. Friesen, who can't legally work in the U.S., does administrative support in the New Hope office, which covers half his rent. His parents pay for everything else. Evenings and weekends at New Hope are devoted to what members like to call "healing," through classes, support group meetings, multifarious readings and lots and lots of prayer. Tuesday evenings there's a house meeting, after which everyone breaks into groups of six to recount their weeks. Monday and Thursday evenings, they gather for "praise and worship" in a spacious room with a piano in one corner. On Tuesday and Thursday nights, they attend classes from 8 until 9:30 or 10, mostly taught by Worthen--in August, they were studying a Christian self-help book called Telling Yourself the Truth. Friday nights, the residents take turn helping Worthen run his drop-in support group. Wednesdays, they play volleyball. Saturdays, they clean, and Sundays, of course, they go to church. Three times a year they have what House Leader Howard Hervey calls "straight men interviews," in which heterosexual guys, often recruited from the church, come to the classes to answer questions about what it's like to be, well, straight. For example, explains Hervey, someone might ask the visitor, "When you see a good-looking guy, what do you feel?" "He might say, 'I want to be his friend,'" Hervey says, which helps the residents understand that responding to attractive people is normal, and that they're not so different from other men. Of course, it would seem that putting 21 gay men, all struggling to repress their desires, in a group home together is a recipe for catastrophe, as was deftly portrayed in the movie Cheerleader. And indeed, says Hervey, "There have been instances where there's been a lot of unhealthy bonding." But since New Hope conceives homosexuality as a never-fulfilled quest for acceptance and positive male affirmation, learning to connect to other men in a non-sexual way is considered essential. "It's a calculated risk," he says of the living situation. "What we've tried to do is make the house a safe place to relate. We need to be able to work through a lot of our brokenness and learn to relate to other men before those other men will accept us. We need to learn to deal with our emotional dependence issues, our immaturity, our victim mentality." If an attraction does develop between two guys at New Hope, says Hervey, the program has a response called "Putting them on Level." "They're not allowed to be in the same room together alone," he says. "If we go out, they're not allowed to ride in the same car together. If we're sitting at the table, they have to sit on the same side so there's no direct eye contact. And then the whole house holds them accountable." Worthen says, "We want them to experience everything they're going to experience within the year they're with us, so we can work it through in the group. It all gets talked about. It's all brought to the group. They get expelled from the program if they hide anything. Everything--feelings, actions everything--has to be brought to the group." NEW HOPE DOESN'T ACTUALLY promise to make participants straight. "There are a spectrum of results," says Worthen, a 71-year-old man with big, rheumy blue eyes, a bulbous nose and a turned-down mouth, who looks quite stern except when he breaks into a warm, crinkly-eyed smile. "It's very easy to stop your behavior, but what you are then is a celibate homosexual. You're not heterosexual. There are degrees of change. Some people do make it all the way to heterosexuality, family and children--we have lots and lots of little babies that are here because of Exodus." Yet he admits that fully 50 percent of the people who come to his ministry return to homosexuality. The workbook that he wrote for participants in the live-in program says, "Our primary goal is not to make heterosexuals out of homosexual people. God alone determines whether a former homosexual person is to marry and rear a family, or if he or she is to remain celibate, serving the Lord with his whole heart." Thus, those who succeed in giving up homosexuality often face a rather lonely life. Five years after completing the program, 44-year-old Hervey says he's no longer attracted to men. He adds, though, that he's also not attracted to women. And two years ago, he had to step down from his first stint as house leader after he had a "sexual fall" with another man. Hervey has a leathery face and blue eyes under a lined forehead. His brown hair is cut in a mullet, and he wears squareish glasses and a tan T-shirt with a picture of bloody nails on it that says, "Not by Nails, By His Love." He doesn't get paid to work at New Hope--he runs the maintenance operation at a nearby plastic injection molding company, a step down from his old job as a civilian contractor doing engineering work on Navy jets. But while he will likely never again be part of a couple, he says he's never been more at peace than he is living at New Hope. He quotes the Bible, "You have been bought with a price," which means, he says, "I'm a slave." "The Bible teaches you're either serving God or serving the Devil," he says in a deep, even monotone. "You're a slave to sin or a slave to righteousness." THERE ARE FOUR PHASES to New Hope's program. During the first, residents aren't allowed to leave the grounds without at least two other people. In the second, they can go out with one other person. When they reach the third phase, they can do basic chores like shopping alone, and in the fourth phase they can come and go largely as they please, as long as they sign out. Throughout, there's a curfew--10:30pm during the week and between 11 and midnight on weekends, depending on which phase the resident is in. Like Friesen, most of the residents are in Phase 3. Some, though, have been kept in Phase 2 for breaking the rules--Dave, 23, was held back after he called phone sex lines twice and then confessed to the group. Residents are allowed to watch two movies on the house VCR during the weekends, provided they're rated G, PG or PG-13. They need special permission to go to R-rated movies in theaters. "They might let you go see something like Saving Private Ryan, something that's violence-oriented. Anything with sex, they say no," Friesen explains. They're not permitted to use the Internet or visit bookstores. Sarcastic, campy humor is verboten. Instructs one of the workbooks, "Watch that your conversation does not show the old lifestyle in an intriguing way, as there may be some men in the program that have not engaged in actual gay sex acts. It is our goal to bring people out of the gay mind-set rather than to reinforce the gay mind-set." Friesen, though, was never really in the "gay mind-set," whatever that is. Before he came to New Hope, he didn't have any openly gay friends. Now he speaks authoritatively of "the gay lifestyle," which he's learned about largely from the older men in the program and at conferences like Exodus, where orators seem to compete with each other in telling of the wretched degradation they wallowed in before Jesus appeared in their lives. One of Exodus's most visible spokespeople is John Paulk, a former male prostitute and drag queen who went through New Hope and is now a father married to an ex-lesbian. He works at the conservative organization Focus on the Family. Another speaker at the Exodus conference was Bob Van Domelen, a former high school music teacher who molested male students for 15 years, eventually serving three years in prison. Today, Van Domelen runs an ex-gay ministry in Wisconsin and helps Exodus with its rhetorical attempt to conflate homosexuality and pedophilia. So it's little surprise that Friesen sees gay life as a vampiric netherworld. "There's not very many ex-gay young people because of the way the gay lifestyle is set up," he said. "[Gays] thrive off young people. Young people are it, and somebody from a really rejected background can go to a gay bar or to a gay community and they are loved and accepted. Then, by the time they're 35 or 40, they're kind of old and used and the gay community is like, OK, we're done with you. That's when they feel, 'I don't want anything to do with this lifestyle anymore,' and then they come here." THAT CAPSULE NARRATIVE IS A staple of ex-gay ideology, one put forward perhaps most forcefully by Frank Worthen himself. Born in San Jose, Worthen lived as a gay man for 25 years--he was actually a pioneer in the gay rights movement. But as he got into his 40s, he says, he was alone and hideously depressed. There were bars in San Francisco that wouldn't admit men his age. The only sex he could get was the sex he could pay for. Some of his friends had killed themselves. So in 1973, when an employee at one of the import stores he owned started evangelizing him, he was ripe for change. He became a born-again Christian and left what almost everyone in the ex-gay movement scornfully calls "the lifestyle." Six months later, wanting to reach back to his old community, he took out an ad in a San Francisco sex paper announcing a support group for men who wanted to get away from their homosexuality. "The first year, 60 people answered my ad and all said they wanted out. Many of them were suicidal," he recalls. Then Worthen's pastor wrote one of the first Christian books about homosexuality, called The Third Sex. Soon, he says, "people began to arrive on our doorstep with their luggage and say, 'My church doesn't understand me, the people in my town reject me and you seem to be the only people who understand what I'm going through.' We didn't know what to do with the people initially, and finally we developed community houses for them so they could live in our church community. That was the beginning of our residential program." In 1975, Worthen heard of a similar group in Southern California. The next year, the two groups held a conference, and 12 ministries attended. They banded together under the name Exodus. Now Exodus has 100 ministries in 35 states in the U.S., 10 ministries in seven countries in Europe, seven in Australia and New Zealand and one each in the Philippines, Japan and Singapore. In addition, there's an ex-gay group for Jews called Jonah and one for Catholics called Courage. Today, Worthen lives with his wife, Anita, who got involved with Exodus because she was devastated after her son, Tony, told her he was gay. Tony is still gay, but he's close to both Frank and Anita--in fact, he and his boyfriend live in an apartment owned by Frank in the same complex as New Hope's residents. Amazingly, when Tony's old lover, George, was dying of AIDS, it was Anita who nursed him through his last months, even though she blamed him for infecting her own beloved boy. Whatever one thinks of the Worthens' teachings, they truly mean well--neither are hate-mongers. They speak affectionately of the men in the program as "our guys" and genuinely believe that they're helping them. They're convinced that homosexuality is sickness and sin, and it's their mission to free people from it. THE PROBLEM WITH helping people Friesen's age, says Worthen, is that they haven't experienced the so-called horrors of gay life firsthand. "We have difficulty with the young people because they haven't had enough experience, and they still think it can work. They may think, 'I've just had the wrong partners.'" And indeed, Friesen confesses that, at moments, "I still have thoughts that I could have a boyfriend, that it could still work for me." That's why Hervey encourages New Hope's younger residents to learn about gay life from the older ones. "I've known a lot of gay couples--men specifically, with women it's different--but I have never met a monogamous gay male couple. Ever," Hervey insists. "They've always fooled around on the side. And I just tell them it doesn't work. It. Doesn't. Work." Nevertheless, Hervey himself was in a relationship for 11 years before he left his lover to join New Hope. Three years later, his lover followed him into the program. Today, they both live there, which in a perverse way seems evidence of an enduring gay relationship. Still, the message that real gay love is a delusion has gotten through to Friesen. He talks about a 36-year-old friend from Exodus who was actively gay for 12 years, saying, "He knows there's nothing there. There's no option of going back. There's nothing to go back to. He hates it. I'm learning from that guy's mistakes. I'm hearing other testimonies saying how horrible it was, and I'm learning from that. A lot of these men have wasted decades of their lives, and now they're in the same place I am. I have my whole life ahead of me." Whether he's moving toward a workable truth or away from any hope for happiness is impossible to say. There are legions of mainstream therapists and ex-ex-gays arrayed against New Hope and groups like it. John Evans, a former colleague of Worthen's turned vociferous critic, has said, "They're destroying people's lives." Jack Drescher, M.D., the chairman of the American Psychiatric Association's Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Issues Committee, calls ex-gay therapy "an abuse of therapeutic authority" and says, "There's clearly a lot of anecdotal evidence of people who've been through these treatments and feel that they have been hurt by them." Yet for Christians like Friesen, God trumps science. The question is whether Friesen's God can also trump sex. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 23-29, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.