![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Getting Promoted

A day in the life of the valley's young Bill Graham

By Michael Learmonth

'THERE, NEXT to the dumpsters." Eric Fanali points calculatingly over the dash of his 1983 Subaru as we sputter down Del Mar Avenue in San Jose. "Every school has a smokeout place. The key is to find it and put posters there."

The rickety Subaru lets out a cough as he downshifts and pulls into a spot across from Del Mar High School. He grabs the tape gun, gives me a handful of day-glo-yellow posters and walks quickly to Del Mar's driveway.

"Anyone coming?" he asks as he places a poster on a sign. "2nd Annual Tomato Head Records Tour," it reads, "featuring: Blindspot, My Superhero, Monkey and The Jamons ... All Ages! $7." He quickly drags the tape gun across the edge of the poster with a deafening "scireeeeeech." After the sign is appropriated we walk up Del Mar and plaster two more posters on lamp posts. Then we cross back to the dumpsters, the "smokeout place." The dumpsters are locked but three crumpled Marlboro packs are lined up on top and stained butts litter the ground. Soon the lunchtime smoking crowd will congregate and deposit a few more. We tape up three posters for their benefit.

"Del Mar is a good school ... for concerts," Fanali says. "All we need are a few kids to see it, then they'll tell everybody."

His work done here, he walks briskly back toward his car. Spotting an official-looking woman in a stretchy green dress blustering up the sidewalk, he conceals the incriminating tape gun next to his leg.

The woman turns the corner and heads to her car. Fanali shoots me a look. There will be no need for a quick getaway today.

"I might drive by in a week or so and check out my handiwork," he says, "just to see if they're still up."

As he pulls away from the school in the Subaru, we continue on a valleywide list of destinations, consisting of high schools, record stores, community centers, coffee shops and a lot of lamp posts in between. For this concert--a record release for the local ska/punk label Tomato Head Records--Fanali wants to go all-out.

Silicon Valley may be ground zero of the information economy, but in the analog universe of local bands and independent shows, the printing press still rules. But this part of grass-roots promotion is underground, below-board and not without its risks from cops, teachers and agro store managers. A few days earlier Fanali had warned me, "There are no rules to fliering."

BACK AT Fanali's office--his bedroom, that is--in his parents' home, the phone starts ringing at 10am and often doesn't stop until he unplugs it when he wants to go to sleep. On a night when there's no show to put on, that can be as early as 8pm.

"Hello, this is Eric and Grand Fanali Presents," he says when he picks up the phone. Sometimes it's his childhood friend Pete Fabricius, who is calling him for the same reason most teenage boys call each other--no particular reason--but other times it's a band manager or record-label executive who wants a piece of Fanali.

"They call and say, 'Can you do a show for a bunch of kids on a Thursday night?' Hell, no! I can't do a show on Thursday [a school night, dumbass] for a band the kids don't know!"

Other times, bands themselves call: "Uh, hello, Mr. Fanali? This is, like, Joe and we have, like, a band and we would really appreciate it, uh ... we just want to do a Fanali show."

"I tell them, 'Look, how old are you? I'm 19, so talk to me, just don't call me Mr. Fanali,' " he says. "It's funny because it's totally like Bill S. Preston and Theodore Logan, Esquire, and you know they're flunking English and they're like, 'Huull-o.' "

Fanali laughs at the thought. The way he hops around his room in stocking feet, he himself would not be out of place in a teen movie. He clads his slight frame (130 pounds soaking wet) in funky thrift-store threads, white socks and intentional highwaters. He combs his black hair into a '50s flip in front and wears nonprescription flattened rectangular black frames on his nose.

All-ages shows make use of the 'burbs.

IT'S BEEN A LITTLE MORE than two years since Fanali put on his first concert, an all-ages show at the Saratoga Community Center with local ska act Monkey and a traveling band from Los Angeles, See-Spot. At the time, Fanali was only a sophomore at Saratoga High, struggling to find his niche, which he was learning wasn't going to be among the highest athletic or academic achievers.

As a freshman, he had been implicated by the police as the ringleader of a group of kids who relieved the monotony of their suburban existence by playing mailbox baseball and otherwise wreaking havoc upon the tranquillity of the good citizens of Saratoga. It was the kind of entertainment that brought ecstatic mirth while his cohorts were around, but after they went home for the night, he felt the guilt of his deeds and the pain of his isolation. He had moved to California from Connecticut just a few years before. Sometimes, after those nights of mischief, he pulled the covers over his head and cried. To this day he doesn't want to talk about it much.

Ultimately, someone got caught and squealed, and Fanali, who had never been in trouble before, found himself holding the bag for a batch of misdemeanors, his story on television and in the local papers. He was sentenced to house arrest and spent the next two months coming home from school and waiting for the voice-match call from the Department of Corrections.

"Everyone thought I was a monster around town," he recalls with a shudder.

Then Fanali did what any alienated, expressive, ambitious kid from the late 20th century might do if locked in the house long enough. He decided to make a movie.

The subject: how he felt as a freshman in high school.

And one of the scenes in Fanali's screenplay took place at a punk rock concert. So Fanali made up a flier that said, "Be in a local movie!" and soon was fielding dozens of calls from aspiring actors from around the Bay Area.

"I never knew there were this many actors," he says. "I thought I was in L.A. or something."

He told all of them to show up and be prepared for an MTV-like concert scene.

Then came the hard part.

On the night of Aug. 18, 1996, kids and actors started showing up at the Saratoga Community Center in droves. In the days leading up to the event, Fanali had become too busy to worry about the actual filming of the concert, so he put a friend in charge of the video camera. Then the band See-Spot showed up with a pushy agent and demanded $300 to play. Since it was a community center event and the city of Saratoga would take all the door proceeds, Fanali was in a bind. He couldn't let the kids down, so he gave See-Spot all the money he had made from pizza sales at the show. Then he gave them all the cases of soda he hadn't sold. Not wanting the young promoter to tank too badly on his first show, Monkey covered the balance. For the next few months, Fanali worked off his debt to Monkey by booking their all-ages shows.

That night the actors eyed each other jealously and did their best Solid Gold voguing for the camera. With their studio hair and MTV clothes they became a sideshow to a scene that would make Fanali forget about the movie and the sadness in his life that inspired him to write it.

"The kids were dancing and the actors were in the back trying to look cool," Fanali remembers. "Kids started asking me, 'When's the next show?' "

By the time he was a junior at Saratoga High, he had become one of those students. Assistant principal Karen Hyde thinks Fanali has the potential of some of the school's other famous alumni: Steven Spielberg, Ed Solomon and Lance Cast. "Unique kids don't come every year," she says. "You get them once every five or six years. So we won't see another Eric for some time."

FANALI STILL hasn't watched the video shot during that first, fateful night. In the chaos of popularity and excitement that followed, he's hardly had the time. Since then he's almost single-handedly revived a local all-ages music scene that had been dying on the vine.

Nia Osaki, bass player for the Muggs, has watched Fanali mature quickly as a promoter. He booked the Muggs' first South Bay show two years ago at the Saratoga teen center. "I've never seen anyone grow as fast as he's grown," she says. "He knows everyone. His shows are so fun because he packs the bills and he's made it so everyone knows each other and goes to hang out."

There are other promoters for all-ages shows, but they have a long way to go to achieve the street cred of the Bay Area's Little Bill Graham. On this night, Eric Fanali is going back to his roots. "Tonight's just for fun," he tells me, picking a pair of burgundy Ben Davis pants and a shiny striped blue shirt out of his bedroom closet. "I love the '80s," he says, grinning.

Tonight's show is at the Saratoga teen center, where Fanali is throwing a concert and party. With typical Fanali generosity, a whopping four bands are on the bill: the Singles, Monster Pete and the Chiefs, the Wonder Years and, coming all the way from Boise, Idaho, the Mosquitones.

"Tonight's a party; I'm not paying anybody and I'm not getting paid," he assures me. "A lot of my close friends will be there, like the kids who always go to the shows."

Fanali's bedroom/office is filled by a waterbed covered with a baby blue afghan. On his walls are posters from every Star Wars movie, posters of the Clash and the Specials and one for the Weird Al Yankovic movie UHF.

Stacks of CDs line his shelves. Almost all are demos sent by various bands, labels and agents. Fanali's CD player broke months ago. So when he wants to listen to something, he pops the CD into his Sega and listens to it through the tiny speaker on his 13-inch TV.

On his dresser in a neat stack are the colorful plastic bracelets he likes to wear and a waxy pile of blue, green and orange earplugs.

His parents, Joe and Ruth Fanali, seem to support Eric's burgeoning business, but they would like to see him start making money at it, or making money at something.

"I've probably never taken home more than 150 bucks, even at shows with more than 500 people," he says. "I feel so bad because I'm friends with all the bands and I'm handing them the money. I could keep a percentage of it, but then I'm taking away from them," he explains with sincerity uncommon in the promotion business. "It's kinda personal. It's not businesslike."

Before we leave for the show, two calls come in to Grand Fanali productions. It's the staff of the Saratoga teen center calling for directions. "Where do we put the PA?" someone asks in a panic. "When are you going to get here?"

When Eric arrives he starts helping clear unnecessary furniture out of the 1896 farmhouse-turned-community center. The bands will set up in the middle of what once was a formal dining room in the center of the house. Then he makes a startling discovery: no food, no drinks, no Nintendo.

"This is all stuff I promised the band," he says gravely. "Notice no one tells me. Nobody wants to give me the bad news."

Christopher Gardner

AT 6PM, THE FIRST guest arrives. Julie Wagner, 18, left her dorm room at SJSU at 4pm, rode the light rail to Blossom Hill and then caught the 27 bus to Saratoga. It was a long trip, almost as long as the time she walked from her dorm all the way to Streetlight Records on Bascom.

Wagner grew up in Houston, but she became interested in San Jose State because her father lived, for a time, in Gilroy.

"I had heard about Eric from friends before I came out here," she says. "It was really good to know Eric early on. He helped me get into the scene faster than I would have."

Even though she knew she wanted to get to know Eric when she came to the Bay Area, she played coy the first few times she saw him at shows.

"Every time I say hi to girls, I usually get a reaction," Eric says. "Julie didn't react, so I was like, 'Who is she?' "

Eric likes to meet everyone who attends one of his shows. The girls, he says, can make or break a show. If they show up, of course the boys will come. And he says they tend to network and get the word out for shows better.

"When you do a show, if you make it safe for girls, the guys will come," he explains. "If I have a chance to give a flier to a guy or a girl, I'll give it to the girl, because they're social. If it's a Grand Fanali show they know it's going to be safe."

The girls seem to like his attention. Perhaps that's because there seems to be so little of the Grand Fanali to go around.

"When I first saw him, I thought he was some cute little kid," says Teshia Cordia, 16, a pretty blonde sophomore at Leigh High School. "He has no girlfriend. I guess it's because there are so many shows and he's so dedicated to it. He has no time to spend with a girl."

Sometimes Eric says the attention he gives girls is misinterpreted. Sometimes he even has to disabuse a girl of the notion that they are actually going out.

"Sometimes girls are very forward, and that's where I draw the line," he says. "Look, I'm Catholic, so I have to be a good boy. I've never been on what you'd call a date."

"I can't commit to anybody," Eric says. "I always go to shows alone, because whoever I'd come with, what would they do?"

He is right, of course. From the time the show begins, Eric doesn't sit once the entire night. He doesn't even stand still. From moment to moment, he's moving a PA, greeting a friend, schmoozing a band member and generally trying to make sure everyone is having a good time.

THE CHIEFS come on second and break the crowd hubbub with a rolling rockabilly guitar riff. Eric stops running for a moment, stands in front of the crowd and starts hopping on his toes and flopping his head around as if it were on a spring. He's wearing his favorite shoes, old-school Converse lows, and his other trademark, black-plastic-rimmed nerd glasses with lightly tinted lenses.

"I never take them off," he says, "even in movies. I feel naked without them."

Apparently the five members of the Berkeley-based Wonder Years feel the same way. All five sport the same black dork glasses, some with lenses and some without.

"I guess it's, like, a thing with kids," Eric says. "They just want to look different."

The special guests tonight are a ska act from Boise, the Mosquitones. The trip from Boise was anything but smooth. All eight Mosquitones had been taking extra shifts at their jobs for months to be able to pay two months' rent in advance to go on tour. But their transportation, a 1973 International school bus, quit in Winnemucca, Nev. So much for the savings. The band pooled its cash and credit cards and financed a $28,000 GMC van.

"It was either that or take up residence in Winnemucca," says band leader Ben Clapp, 21.

It was a major commitment for the band. They will be paying for that behemoth for the next five years--a daunting task considering that all the Mosquitones hope to get out of tonight's gig is a little gas money and a place to crash for the night.

Clapp had heard of Fanali from a South Bay punk band, the Adversives, which played a show in Boise. Last year, the Mosquitones played a concert in honor of Eric's birthday. Because Fanali convinces the community center director to part with half the evening's take, the Mosquitones get paid $70. Until then, they're pooling their resources for a snack at the vending machine.

All worth it, says guitarist "Babyface" Dave Redford, 22, even though the Mosquitones are several years older than most of the teens at the show.

"The kids are a lot more fun," he says. "They appreciate it more. People at bars are just there to drink. They don't want to see some shitty band from out of town."

It's been a long day and Babyface is looking for a whisky-drinking buddy before the Mosquitones go on. The only other sign of alcohol use came during the break between the Chiefs and the Wonder Years when a young, pimply faced kid pranced through the house holding a handful of denim between his legs and howling, "We've got beeeerz out baaaack!"

Fanali says that usually after the shows they find a few empty 40-ouncers in the parking lot, but generally the shows are drink- and drug-free. Fanali himself doesn't smoke or drink, not even coffee. "I've never had a show broken up," he boasts.

Phone Home: The phone at Grand Fanali Presents, which is headquartered in Eric's office/bedroom at his parents' house, rings from morning until night.

KIRSTIN MUNRO is one of 10 or so kids Eric says are Fanali show regulars from Saratoga. She goes, somewhat against her will, to Castilleja Middle School in Palo Alto. Munro publishes two newsletters online, one with her friend Michelle. At 15, she articulates a pretty sophisticated version of the punk aesthetic. It is a subculture that eschews money and class, and holds purity of intent and devotion to the music above all things. People who go to shows to drink and who don't know the bands or the music are the lowest of the low. Band members are respected, she says, but they are not worshipped.

"There are no rock stars," Kirstin explains. "During the shows, the other band members are in the audience."

More than a concert, the people who attend are part of a community. The kids know each other, no matter what part of the county they're from, and everyone has something to contribute to the scene, be it a flier, Web site or newsletter.

There are few bands that can get Kirstin, Nicole and Fanali to leave their cozy subculture and go see a band in the crass and boozy over-age world. The Donnas from Palo Alto are one of those bands. So the three held their noses and went to a night club on a school night to see the last Donnas show.

"Me, Kirstin and Nicole were the only teens there," Eric says. "We were just some innocent kids from Saratoga."

Far from their community center roots, the Donnas now appeal to a crowd that Fanali holds in the highest contempt.

"The way it was billed was old guys get to be with young girls," he says. "All that were there were guys with a beer in one hand and their other hands in their pockets. I think it was pocket pool."

"Drooling old men," Kirstin chimes in.

A fight broke out in the club after the Toilet Boys, a cross-dressing punk act, provoked some fratty boys in the pit. When the Donnas came on, Donna "A," Brett Anderson, came on the mike and shamed the miscreants. "Please don't beat us up," she said. Then they played a fast set and were gone.

"On the last note we got the hell out of there," Fanali says.

Shows infected with alcohol-induced aggression are a reason that Munro says Fanali's community center shows are so important.

"We need someplace where everyone's not drunk and gross," Kirstin says. "The drunk older people are just there to go to the bar and pick up chicks or whatever."

AS THE TEEN CENTER show wraps up around midnight, the party moves to the Cupertino hills, where a 15-year-old named Avi is known to be having a slumber party, and to have permissive parents. The Mosquitones, the Wonder Years and a few assorted friends of Fanali caravan there and find six 15-year-old boys in sleeping bags. They have Cokes, cold pizza and an Astrojump in the yard. The Wonder Years strip down to their skivvies and hit the heated pool. The Mosquitones pack 10 people into the Astrojump. Avi invites the Mosquitones to spend the night, saving them from a shivering night in the van.

"They were really nice," Fanali says. "The Mosquitones and those kids stayed up until 4am talking."

Once again, as he has for the past two years, Fanali went home with a smile on his face but no cash in his pocket. His parents have been pushing him to make some money on the Grand Fanali gig. The 1983 Subaru is on its last legs, and when it finally gives out, they expect him to get a real job to buy a new car.

Then there's the whole moving-out question. Theoretically, he wants to. But that would mean leaving the comfortable bedroom, the refrigerator and at least some of his carefree lifestyle.

When we talk about this, driving from the Music Warehouse in Camden, he starts asking questions. "How much money will I need to move out? How much would a Honda Civic cost per month?"

I'm afraid the answers to those questions are enough to let the wind out of even the Grand Fanali's sails. He says he can imagine moving into an apartment with his best friend, Pete Fabricius, 19, who also lives at home and, like Fanali, is a sophomore at SJSU.

His parents would like to see him independent, but still cling to him, their only son. His father still videotapes many of his big shows and helps him sweep up after. His mother cuts his hair but warns him if he dyes it blue, she'll stop.

"My parents have been pressuring me to take money [at the shows]," he says. "They say, 'You deserve it,' and maybe I do, but I'm not going to take it from a band."

"I've talked to him about this," says Mike Park, founder of Monte Sereno-based Asian Man Records. "If he wants to make a career of it, he has to start keeping some money."

Park, a veteran of the music industry, says Fanali is "in it for all the right reasons," but wonders if the sweet boy everybody loves will be able to harness the asshole inside to take what he's worth and to deal with the industry leeches who are already trying to take him.

"To be a promoter you have to be a dick sometimes," Park says. "I don't know if he has it in him. You have to have a killer instinct about screwing people. You've gotta play hardball with agents and promoters."

I ask Fanali when he thinks he'll stop doing all-ages shows. When he turns 21? 25? On this, Fanali seems to be truly stumped. At 19, he's within a year or two of outgrowing completely the crowd he's become a ringleader to.

"I don't want to grow up ever," he says. "The world sucks. Happiness in the world today is all about innocence."

For information on Grand Fanali shows, email [email protected].

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Christopher Gardner![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

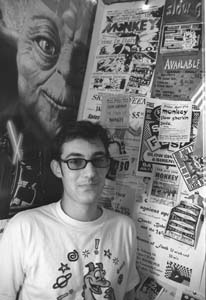

Feel the Force: Concert promoter Eric Fanali with his collection of all-ages showbills. His trademark: a generous lineup of local bands, lots of friends, for one low price.

Feel the Force: Concert promoter Eric Fanali with his collection of all-ages showbills. His trademark: a generous lineup of local bands, lots of friends, for one low price.

Christopher Gardner

Local Music on the Web:

Bay Area Ska

The List, a comprehensive schedule of Bay Area shows.

Kirstin Munro's Web magazine, Black Sheep

Tomatohead Records

Asian Man Records

From the November 25-December 2, 1998 issue of Metro.