Troublemakers: Through the efforts of the Laogai Research Foundation, Milpitas' most famous dissidents remain a thorn in China's image.

Chinese dissident and human rights activist Harry Wu continues his fight to expose China's injustice system

BLOOD RUNS thick behind the bamboo curtain. "The world knows that perhaps a few people were killed at Tiananmen Square," writes Harry Wu, Chinese dissident and human-rights activist. "I say the incident at Tiananmen Square was peanuts. Millions of people have been lost in the laogai. Every one of those lives was precious."

Laogai, the "reform through labor" prison-camp system, is China's sword--its tool of political suppression, the specter behind the culture. Until Wu, a laogai survivor of 19 years, waged his crusade against this equivalent of the Soviet gulag and struck his first blow at China with his role in Sixty Minutes' "Made in China" report, no effective voice had risen to unmask the evil. Wu, now a resident of Milpitas, remains one of the most troublesome thorns in China's side.

In June 1995, Wu made his fourth return trip to China, this time in an attempt to investigate a possible link between China's loans from the World Bank and the prison camps. At the Kazakhstan border, Wu was identified and captured as one of China's 49 most wanted criminals (the line between political dissident and criminal is slight in China).

He was transported back and forth across China and imprisoned, suffering two harrowing months of interrogation under constant guard. His arrest touched off an international incident that ended only after his conviction for stealing state secrets and subsequent expulsion from China.

Still, in the recent wave of Chinese nationalism sweeping around the world, Wu finds few Chinese willing to go public with their support for his cause. Even in Silicon Valley, where he has lived for 11 years, Wu receives a general hum rather than a roar of support from the local Chinese community.

"Fundamentally, Chinese around the world are with me," claims Wu in our interview. "But most think we could settle it behind closed doors. They say, 'No need to get the whole world involved and make China lose face.' "

The problem arises out of the public's, Chinese-Americans included, confusion over the real issue of Wu's crusade. He admitted in his interview that there are public misconceptions plaguing his argument against the laogai, some of it propagated by China and its supporters.

Is Wu protesting China's inhumane treatment of prisoners? Is Wu against slave labor? Is Wu against imprisoning political dissidents? Why isn't he fighting for the rights of normal Chinese rather than those of prisoners? The true answer, the impetus of Wu's campaign, eludes even most of those Chinese-Americans who vehemently take sides on the issue.

Laying Into Laogai: Wu's persistent crusade is aimed at China's terrifying prison-camp system of "reform through labor."

THE DEFINITIONS and semantics of laogai; Wu's estimates and China's official numbers of prisoners; the ratio of penal to political prisoners; the debate over China's alleged cover-ups; and the recounted horrors of camp survivors--these concerns often obscure the basic fact that there exists an institution in China whereby people who openly disagree with the government are sent without trials to serve indefinite terms of incarceration, to work, to suffer and, in some cases, to disappear forever without a trace.

Theoretically, the system consists of three classifications: "re-education through labor," "reform through labor" and "forced job placement personnel." Political dissidents and penal criminals are sent to labor camps together. All prisoners must work, and the fruits of their labor are used for either domestic consumption or export. Even after the dissidents are deemed "reformed" (as in Wu's case), few receive permission to go home. Instead, they are relocated and forced to work for minimal wages with little or no liberty beyond the work compounds.

Given the fronts on which Wu must fight his battle, it is easy to see the reason why some don't fathom his real motive. Wu's demands for a ban on products made by forced prison labor are actually an attempt to call international attention to the injustices of laogai.

In an interview with Ching-Lee, Wu's wife, she recalls, "When I first met Harry, I asked him, 'As long as they are treated well, shouldn't [Chinese] prisoners work for their food?' He said, 'That's an entirely different issue.' "

Even more telling is what Ching-Lee feels is a deep reflection of her husband: "Harry said to me, 'Life is so short, so valuable. If a person wants to sing, let him sing. If a person wants to read, let him read. If a person wants to speak his mind, let him speak. Why do they [the Chinese government] have to lock people up for that? Let them live their lives.' "

Because they took away his life and his comrades' lives, Wu crusades for the demise of the laogai. But without this control system, the government has no way to suppress uprisings short of massacres such as Tiananmen Square. Without the laogai poised as the proverbial executioner's blade over their necks, Chinese will likely--if not inevitably--embrace free speech. And from there, it is reasonable to say democracy is not a far leap ahead.

In this perspective, slave labor, international trade, World Bank loans to China and human rights are vehicles, weapons and stepping stones for the larger issue of achieving democracy.

Wu is not the lunatic, martyr or intrepid adventurer that some make him out to be. He is a humble but intent man. "I am not a martyr. I am afraid of being sent back to the laogai. In China, I was always afraid of getting caught. I want to live out the rest of my life, but I want to speak my mind."

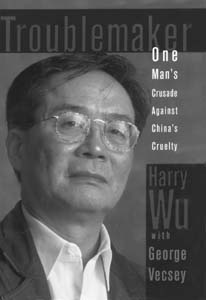

In his new book, Troublemaker, Wu writes of his prison experience:

- I came back from the land of the skeletons. I was not a hero; I would have to turn myself into a beast many times, fighting and bullying and lying and confessing, but I would survive. The diplomat James Lilley, who said that I have "a martyr complex," knew nothing. His were the pompous words of a privileged Westerner. If I wanted to be a martyr, I had my chance back at Qinghe Farm [a laogai camp]. I wanted to live.

In the Bay Area, Wu's Chinese-American adversaries denounce him as a liar selling out China for his personal gain. George Ku, a prominent Chinese-American businessman with strong business ties in China, is Wu's most aggressive detractor.

Shortly after Wu's 1995 return to California from China, Ku formally challenged Wu to a public debate on human rights in China. Ku and his supporters question the source of funding for Wu's Laogai Research Foundation, Wu's estimates of the number of prisoners in the laogai and the accuracy of the film footage Wu shot for the BBC and CBS.

Wu declined the debate and, consequently, lost some local support. When asked about why he did not accept Ku's challenge, Wu replies, "He is a businessman. He stands to gain a lot with America's trade with China. He admits he has been back to China 50 times. He wants to talk to me about human rights? I don't want to waste my time with him."

WU, WHO could earn an easier living at his old job as an administrator in a high-tech company, works out of his home and keeps a gun as insurance for the threats made against his life. His parents-in-law live with him and Ching-Lee in Milpitas. Their modest tract home sits in a suburban middle-class neighborhood of mixed races.

A deluxe motion-sensing system guards the front entrance. Just inside the front door, a row of shoes flanks the foot of the wall. A halogen torchiere, the inexpensive, assembly-required kind, lights a small living room. A white sofa set corrals a glass-topped, iron coffee table with its feet booted in kitchen aluminum foil to prevent carpet stains. On the walls are prints and an occasional framed Chinese calligraphy.

Upstairs, the headquarters of the Laogai Research Foundation occupy one of the small bedrooms. The foundation operates on donations from friends and fees from Wu's speaking engagements. Wu and Ching-Lee work in their cramped office toward a "dream that someday the word laogai will be as well-known to the world as Holocaust and gulag."

Sitting in her living room, Ching-Lee says she likes living in Milpitas and humbly reflects on her meetings with Margaret Thatcher and Newt Gingrich, and her adventure with the press. When asked about the local Asian criticism of her husband's lack of involvement in rallies and meetings, she says, "People don't realize how busy Harry is. Last year, he gave over 100 lectures. He wrote a book. He worked on the foundation reports. He testified at congressional hearings.

"Last November, he was home two days. This November he stayed home only two days also. There are many issues out there. Harry is 59. He is human. He can't do everything. He is doing his job; other people should do the other jobs."

On the wall of their office hangs a calligraphy of an old Buddhist saying that Wu embraces as his guiding light: "The rain falls into the ocean, neither increasing nor decreasing." He says, "To me this means, 'Stay calm. Endure.' "

He chuckles when offered an alternate interpretation: "Like the ocean, China is ancient and its population is vast, always enduring all hardships, all sorrows." Wu says this interpretation is also valid, true and very much Chinese.

For Chinese, nationalism permeates every aspect of life. Wu thinks China's hybrid form of capitalism won't lead to democracy as the United States hopes, but will lead instead to a new form of a totalitarian, supernationalistic military state.

Historically, the roots of much of China's problem, Wu explains, "is the fact that Chinese cannot distinguish between government and the motherland. [Even] until today, you can see so many Chinese dissidents over here [in America], they disagree with what I did [exposing the laogai]. They say, 'Why do you say bad things about our government to stop America's trade with China? No matter what, the money goes back to our motherland. You hurt the motherland.' "

Wu adds, "Chinese-Americans live in America, they eat, think and work like Americans, but when the issues turn to China, they think like mainland Chinese--like they never left."

On the Road to Resistance: Harry Wu and his wife, Ching-Lee, in a rare moment of relaxation.

BUT MAYBE Wu was never truly Chinese; by his own admission, he never viewed the world through peasant's eyes. He didn't even set eyes on the real China, the rural China, until his later years in college.

Born in 1937, into China's privileged class as a son of a wealthy Shanghai banker, Wu was destined for the laogai. He admits that his bourgeois world of Catholic dogma, baseball, Victor Hugo's Les Miserables, Melville's Moby-Dick and Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea made him ill-suited to Mao's China.

Mao declared a period called "let the hundred flowers bloom" during Wu's college years. The program supposedly fostered new ideas and directions for China's intellectuals. Encouraged, Wu obeyed and spoke his mind at a study group on a current event.

He cited the Soviet Union's sending troops into Hungary as a violation of international law. What no one knew was that Mao's right-hand man, Zhou Enlai, had been behind the plot in Moscow with Khrushchev. Consequently, Wu "blossomed" himself onto a road that led directly to imprisonment. A few months later, his personal life began falling apart under Party scrutiny. On April 27, 1960, at 23 years of age, Wu was arrested and charged with drummed-up crimes and, without warrant or trial, sent to "re-education through labor" for three years of "reform."

Three years became 19 before Wu, former baseball player, literature lover and geology student, walked away a free man at the age of 42. Publicly denounced by his family and forgotten by his old sweetheart, Wu ventured into a new world alone. He couldn't turn to his family because they had already suffered the stigma of his "reform."

The intervening decades also scattered his siblings and reduced his once proud father to a bitter old man whose last wish was that Wu not make the same mistake as his father. On his death bed, Wu's father told him to leave China.

IN Troublemaker (written with George Vecsey, a New York Times sports columnist, who has collaborated on several autobiographies), Wu's famous arrest in China and all the subsequent events account for about a third of the text. The balance of the book reaches into the fabric of his early childhood, draws sharp vignettes from his time in captivity and compiles startling excerpts of his three earlier trips back to China.

While the content of Troublemaker overlaps with his two previous books, Bitter Winds: A Memoir of My Years in China's Gulag (with Carolyn Wakeman) and Laogai--The Chinese Gulag, this book stands well on its own as the most complex and comprehensive approach to laogai, and Harry Wu, the man and his present opinions. It also serves as a medium for Wu to explain certain discrepancies in some the film footage made by the BBC and CBS.

Given Wu's halting command of English, Vecsey's pen appears prominently, particularly in the beginning of the book, but enough of Wu's obstinacy and declarative speech glare through to show his character:

-

I want to expose the system [laogai]. I am the needle in the heart, the bone in the throat. Truth is on my side. I went back to China and came out with evidence of evil. This is just the beginning.

Spurred by Wu's extraordinarily detailed recollections of events and dialogue, Vecsey pumps salvos of suspense into the beginning of the story, expending himself well before the story reaches its midway point.

Once Wu falls deep into the hands of the enemy, Vecsey relies too much on Wu's journal of events and fails to dramatize each probe of the interrogator. The book is neither a spy thriller nor a follow-up of Bitter Winds. It's more of a summary of Wu's travails crowned with his "international event" of an arrest.

The story begins with the attempt by Wu and his colleague Sue Howe to slip into China from a remote corner of Kazakhstan, and ends with Wu's reflections and speculations.

In between, Vecsey craftily splices current events with flashbacks selected to affect a linear history of Wu and his work. This is worthwhile for a reader unfamiliar with the Wu saga, but it may be rehashed news for those well acquainted with Wu's work.

Ching-Lee's spearheading of the lobby to free her husband stands out as one of the book's highlights. An ordinary woman, neither fluent in English nor familiar with the demands of the media, she plunges into the brawl and wins with some very entertaining and revealing anecdotes about politicians and the power of the public eye.

Troublemaker offers some riveting revelations, not the least of which are Wu's candid insights about Chinese culture. The most terrifying discoveries are Wu's investigations into China's bustling export of human organs derived from executed prisoners. Although the practice is alien and repugnant to Westerners, most Chinese-Americans harbor no doubt about China's capability for such atrocities.

Wu's entire story may seem very strange. Originally arriving in America as a visiting scholar to UC-Berkeley, Wu, with only $40 to his name, slept in the parks among the homeless at night, fried doughnuts in the daytime and lectured for free at the university. Through it all, he was able give his old nemesis, China's Communist government, the figurative finger. First and last, Wu declares, "I am a traitor to Communism, but I am not a traitor to the Chinese people."

Harry Wu will read selections from and sign copies of his new book on Dec. 12 at 7:30pm at A Clean Well Lighted Place for Books, the Oaks Shopping Center, 21269 Stevens Creek Blvd., Cupertino. (408/255-7600)

Troublemaker: One Man's Crusade Against China's Cruelty by Harry Wu (with George Vecsey); Times Books; 328 pages; $25 cloth

Special thanks to Michael P. Kemp.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)