![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Blood In, Blood Out

How do you punish a prison gang that thrives in prison?

Let them kill off their own members, one by one.

By Justin Berton

ROBERT VIRAMONTES WAS WATERING his rose bushes the day his assassins came for him. He was standing in front of his home in Campbell on Palo Santo Drive, his back to the street. Viramontes, 44, a.k.a. "Brown Bob," had spent most of his life inside California's state prisons, rising to become one of the highest ranking members of Nuestra Familia, the notoriously vicious Northern California Latino prison gang. After serving NF for 20 years Viramontes had paroled, for good. He was enjoying his new life in "semiretirement," which the Nuestra Familia Constitution guarantees to any member who survives two decades, or achieves age 50. In gang terms, it was supposed to be the only way to get out alive.

Viramontes moved into a one-story home on a nice, wide street, and lived there quietly with his wife of 22 years, Esperanza, and their two sons, ages 17 and 6. After two years of suburban living, he had strayed far away from gang business altogether, and spent Sunday afternoons tinkering on his Chevy pickup, which he nicknamed "Lucille."

The biggest disturbance came from the scores of local gang unit hotshots who stopped by the home, continually, hoping to gain inside information on NF in exchange for any, say, future parole violations. Yet, associates say Viramontes never rolled over on his former associates. Instead, he spoke to young gangsters through a program called "Mothers Against Gangs," preaching against a thug's life, period. He hired tattoo artists to cover the massive "Nuestra Familia" emblem across his back; he worked honest jobs mopping floors and cleaning offices; he took up gardening.

On April 19, 1999, at about 6:45pm, a Ford Explorer carrying three young men pulled up to the curb in front of Viramontes' home. It had been stolen from a driveway in the Rosegarden neighborhood, from an owner who kept a key in the glove box.

The driver, Albert "Beto" Avila, waited at the wheel, while two men leapt out from the passenger side doors. Both wore T-shirts and shorts. The first shooter was named David "Dreamer" Escamilla, a member of the NF's bush league, the Northern Structure, who was out on parole after doing time for attempted murder.

The other shooter, Santos "Bad Boy" Burnias, was a longtime NF member, who had also done a stint for attempted murder. A fourth person, Antonio "Chuco" Guillen, the San Jose NF underboss, supervised from another car parked down the street.

Dreamer and Bad Boy walked up the driveway toward Viramontes, and both began shooting. Viramontes turned toward the open garage and tried to run into his home. As he crawled toward the door, Viramontes was hit seven times in the chest, back, legs and arms. One bullet grazed his left cheek. Dreamer got so close to his target, blood splattered back onto his hands.

Esperanza, who was making dinner in the kitchen, ran out the front door, around to the driveway, and watched the assassins pile into the SUV. She pointed at them and screamed: "What have you motherfuckers done?" One of the men stuck a gun out the window and pointed it at her. Then they drove away.

THE MURDER OF Robert Viramontes was, like most hits on higher-ups, ordered from inside Pelican Bay State Prison, Nuestra Familia's headquarters. Located on a desolate patch of earth near the Oregon border, Pelican Bay is a bloody place. In the past three years alone nine inmates have been killed at the hands of their fellow inmates. In one riot last year, involving 250 inmates, 32 prisoners were stabbed and one was killed by a guard's bullet to the back of the head. Only California's most violent inmates are sent to "The Bay," and only the most violent of those are locked inside the prison's Security Housing Unit, or SHU, where inmates are kept in their cells 23 hours a day. Today, all NF lords live inside the SHU.

The NF mantra is "Blood in, blood out," and Robert Viramontes satisfied the first part of the deal in 1978 when he and NF members were convicted of manslaughter for hanging an inmate they thought was a snitch. Viramontes didn't stick around for the consequences; he escaped from Monterey County Jail, fled to Mexico with his wife, and was captured after several armed robberies and assaults. He did his time at San Quentin State Prison, the unofficial birthplace of Nuestra Familia, and adapted to the gangster's life.

Viramontes was well read, on all subjects, and well known for his charisma. As a rising star, he was responsible for indoctrinating the up-and-coming talent to the two major tenets of NF: to "promote the Mexican race" and swearing a lifetime of allegiance to one another. Recruits were schooled in making weapons, Mexican-American history, and boot camp-like chants, used at night to intimidate other inmates as they slept. Once chosen, any NF member who betrayed his fellow carnals was subject to Article 2, Section 5 of the NF Constitution: "AN AUTOMATIC DEATH SENTENCE WILL BE PUT ON FAMILIANO THAT TURNS TRAITOR, COWARD, OR DESSERTER [sic]."

Viramontes' devotion to the gang promoted him to the highest echelon of NF, the select Organizational Governing Board, also known as "La Mesa." There are currently an estimated 1,000 NF members--both inside and outside prison--and the vast majority are "soldiers. Above them are lieutenants, and then captains. At the top of the pyramid is La Mesa, a three man tribunal. La Mesa approves membership, oversees promotions and policy changes, and, more often than not, orders hits on its own members.

When Viramontes first paroled from San Quentin in 1992, he returned to his home in the South Bay and took his first step toward leaving NF. He approached Mothers Against Gangs about being a speaker for them, getting so nervous for his first presentation that he asked his family to wait outside. After each subsequent speech, he took notes on his own performance. He transformed his body to cover the giant NF tattoo on his back.

At the same time, the Santa Clara County district attorney's office was engaging in an expensive, and thorough, war against Nuestra Familia--a war that would eventually tangle up Viramontes.

The DA's investigation targeted two back-to-back slayings of known NF members on the East Side and concluded with the massive indictment of 21 NF members for racketeering and murder. Preparing for the high-profile trial, the judge considered building a makeshift courtroom, one loaded with heavy security. In the end, the county spent more than $10 million on prosecution and security costs, and of the original 21 defendants, only four were convicted--the rest took guilty pleas, and made deals. Viramontes was subpoenaed to testify to the grand jury, but was one of the few who refused to talk about his role in the gang. The answers he did give contradicted other sworn testimony. In the process, Viramontes was convicted of perjury and sent back to San Quentin in 1994.

When Viramontes returned to San Quentin word spread quickly through the intricate NF communication network that in his two years on the outside, the man known as Brown Bob, once one of the hardest, most trusted bosses, had turned soft. How the rap spread is unknown, but NF members, who are sometimes separated from one another for their gang affiliation, can share information in a variety of ways. They can "fly kites," or wilas, which are small notes attached to a strand of elastic, pulled from the waist band in their jumpsuits, which are then expertly flung into another cell; they can make phone calls to members in other prisons, via "three ways," by simultaneously phoning a member on the outside, who holds the two phones to one another; they can hide coded writings and documents, such as hit lists, inside reams of legal papers, which are off limits to guards' searches--and use their lawyers as unwitting couriers. Or, they can simply talk face-to-face in the exercise yard.

Inside San Quentin, Viramontes came across Chuco, the San Jose NF underboss, who was in for a drug possession charge. Chuco noticed Viramontes' back, and saw his recently tattooed Aztec figure disguising his NF emblem of a large sombrero with a knife and three drops of blood. According to NF member Anthony "Chavo" Jacobs who by seniority had "the keys to the yard"--and was responsible for all that went down in the exercise area--Viramontes' cover-up tattoo work caused Chuco to feel "ashamed." And when Chuco learned Viramontes had spoken on behalf of Mothers Against Gangs, Chuco remarked, "He's poisoning young minds."

Then Viramontes made what proved to be two fatal mistakes. Through the network, Viramontes announced he wanted to revise the gang's policy on "door pops." At the aging San Quentin facility, rows of cell doors sometimes malfunctioned and opened unexpectedly. And sometimes inmates intentionally jammed the cell doors and pried them open. Whenever the doors popped, NF policy called for an instantaneous attack on all enemies. According to Jacobs, who distributed Viramontes' directive, Viramontes suggested NF members now simply "stand their ground, and act aggressively only if the enemy acts aggressively."

Viramontes followed this first policy revision with another: he called for a truce with NF's greatest enemy, the Mexican Mafia (EME). The Mexican Mafia is comprised of surenos, or southerners, while NF is a strictly norteno gang. (Nortenos are any Hispanic gang member who lives north of Fresno. Likewise, surenos are from points south of Fresno. ) The long-standing NF-Mexican Mafia edict had been simple: Kill the enemy whenever possible. Brown Bob's call for peace was not well-received.

The two issues put Viramontes under investigation by his fellow La Mesa officers in prison. Viramontes' declarations caused severe discontent among the rank and file beneath him. Factions formed. Whenever policy disputes arise among heavyweights within NF, the winning platform goes to the boss who lives longest. So much for lifelong loyalty.

In early 1998, fellow La Mesa heavyweight Gerald "Cuete" Rubalcaba ordered Viramontes dead. The "filter," or official paperwork announcing the hit, came down to Jacobs, who, by this time, had developed a close friendship with Viramontes. Jacobs told Viramontes he was marked, but promised he wouldn't let it happen in his yard. On the outside, however, both knew things were different. "If you see me coming with another person, run," Jacobs told Viramontes. "Because I'm not coming to shake hands."

From that moment, Viramontes could have requested to hide in protective custody; most inmates who prove they've been issued a death sentence usually do. Viramontes chose to stay put.

Out in the yard, enemy Chuco volunteered to kill Viramontes immediately. He followed protocol and went to Jacobs first, but Jacobs denied him, creating a story to save Viramontes. Jacobs reasoned a yard hit was a "waste of manpower." It took two soldiers to hold Viramontes down, and a third to knife him. The gang was low on numbers at Quentin, and sending three men to solitary wasn't worth it.

Chuco agreed. He'd wait until they got outside.

IT WAS TWO YEARS until Chuco made good on his word. At first, it seemed that the wait had been worth it, and the hit had gone well. Immediately after Viramontes was left for dead in his Campbell garage, Beto drove Dreamer and Bad Boy in the SUV to a waiting car at the La Valencia Apartments on Budd Avenue as planned. Chuco, satisfied that the killing had been a success, took off in another direction. At the exchange point, driver Beto's responsibility was to "burn" the stolen Ford Explorer of fingerprints. He could wipe it down or set it on fire. It was his choice.

Beto had nine children, all from the same woman. He made money dealing crank, and did tattoos on the side. His own skin bore all the typical gang markings: "San Jo Solider" on his neck; "X4" above his left ear; "Norte" on his hand. Two more suggested NF affiliation: a huelga bird on his neck and a solid five-point star--representing the North Star--on his forehead. Yet Beto wasn't an official NF member. He'd last visited prison way back in 1993, and he'd never come within sniffing distance of the SHU at Pelican Bay. Still, he hoped the Viramontes hit was his ticket into NF.

At about 8:00pm, a little more than an hour after the murder, the four men checked into the penthouse suite at the Residence Inn in Sunnyvale. Ringleader Chuco's sancha, or mistress, Nadine Serrano, used her credit card to get the room, while the men waited in the parking lot. More women showed up later to join the three others, and by 11:00pm, they were all in the pool, swimming.

Serrano brought a camera with her and pictures show various poses of Dreamer, Bad Boy, Chuco and Beto--arm in arm, drinking beer, eating pizza, sitting in the hot tub. But sometime during the party, Beto made a disturbing confession to Dreamer. Beto admitted that, in the rush to finish the job, he forgot to wipe down the steering wheel or any of the door handles for fingerprints. Dreamer, who had also hoped the Viramontes hit would quell any doubts about his loyalty to NF, just shook his head.

DAVID "DREAMER" ESCAMILLA grew up on San Jose's East Side as the nephew of a Santa Clara County sheriff's deputy. Instead of following a path into law enforcement, young David helped start a gang, the East Side Hoods. He did a stint in California Youth Authority in his early teens, escaped, and within 48 hours participated in a drive-by shooting on gang rivals from the back of Mazda pickup truck. No one was killed, but several were wounded. David got his nickname, according to one friend, from a girlfriend who teased him about his utopian visions of the future. Another associate says David was quiet, and spent a lot of time by himself.

In reality, Dreamer carried a gun in his waistband, graffitied his body in gang tattoos, and shook down punks for game. During an interview with a detective who was investigating Dreamer's role in a homicide, Dreamer boasted he practiced his shooting skills on rabbits. "They're real fast," Dreamer said. "You have to be a good shot."

In prison, Dreamer joined Northern Structure, a recruiting gang for the more prestigious NF. Northern Structure members, who do much of the heavy lifting for the NF to prove their worthiness, are considered hermanos until the day get pulled up to the NF; then they are carnals.

In September 1998, after Dreamer paroled for attempted murder, he celebrated his return to society with his family at a barbecue. Guests included his uncle Frank, the deputy with the Santa Clara County sheriff's office. Also in attendance was Frank's son, Ray, a first cousin to Dreamer who was about the same age. Ray wanted to become a police officer, like his father, and had completed training at the Police Academy and the Corrections Academy for prison guards.

After the barbecue, even though they were operating on different sides of the law, Dreamer kept in contact with his cousin. Dreamer didn't keep in touch with his uncle Frank, but their paths would cross, no matter.

ON THE TUESDAY MORNING after the killing, Dreamer sought refuge with his older brother, Angel, at his East Side home. Angel said Dreamer carried a copy of that morning's San Jose Mercury News, which contained a blurb about a gang boss's murder in Campbell. Dreamer didn't offer much in the way of an explanation to his brother. "[Dreamer] just said that person was no good and he had to be dealt with." Dreamer spent a few days hiding out at Angel's house, watching television, drinking Budweiser beer--his favorite, making phone calls, and thinking about his next move.

On Thursday, April 22, Dreamer called his cousin Ray and asked him to pass along an important message to his uncle Frank: Stay away from Brown Bob's funeral. A second hit was happening at the service, Dreamer said, on a man named "Alex"-- and he didn't want his uncle caught in the crossfire.

Ray called his father and learned that, indeed, he was scheduled to work security detail at the service. Sometime after Ray's phone call, deputy Frank Lopez drove to his mother's house that night for a meeting with his sister, Dreamer's mother. In his grand jury testimony, Lopez quotes himself as informing his sister, "Your son may be involved in a homicide."

In a flurry of phone calls from his mother's house, at about 9:30pm, Lopez finally reached his other nephew, Angel. According to Angel's testimony, his uncle Frank told him, first, that "he didn't want to know anything that was happening" and second, that Dreamer should turn himself in to authorities.

Then Lopez asked Angel to pass another message to Dreamer--one that contradicts his advice for Dreamer to turn himself in. Angel testified: "I had told (Dreamer) what my uncle told me--for him not to show up somewhere the next day because he would get in trouble the next day."

Near midnight, Angel and his uncle Frank spoke again, in another a tearful conversation. According to his testimony later, Lopez didn't think to ask Angel if Dreamer was involved in the Viramontes homicide. He also didn't think to ask Angel to reveal Dreamer's whereabouts. "I was too emotional to think about it," Lopez said.

The next morning, Lopez briefed the Morgan Hill Police Department on everything he claimed to know: that "sources" told him a hit was planned at the Viramontes funeral on their turf, and that it involved a man named Alex. But Lopez didn't tell the officers that his sources were his son Ray and his nephew Angel.

The funeral was loaded with well-armed officers in SWAT gear, and a helicopter buzzing over head. After the service, Frank Lopez says he drove from Morgan Hill up to the Campbell Police Department. He only got as far as the parking lot when he ran into an investigator and asked if his nephew, Dreamer, was involved in the Viramontes slaying. Lopez says the investigator told him "no."

THE HIT ON "ALEX," an NF member who had refused Dreamer's invitation to assist in killing Brown Bob, never went down but things began to worsen for the four men on the run. On April 24, Chuco and Bad Boy drove up to South San Francisco to escape the heat coming from the Campbell investigation; whenever gang hits go down, parolees are the first bodies rounded up and interviewed. For the ride north, the two men brought along their girlfriends, Nadine Serrano, and Leionna Rodriguez, 25.

They all hid out at a fellow NF member's apartment just off Highway 101. Nadine later told investigators she was inside, sitting on the couch, listening to music, when she spotted a red boxing glove, the smaller, lighter make, typically used for sparring. She picked up the glove and found a 9 mm handgun inside, the one Bad Boy furnished in the Viramontes hit.

NF policy explicitly states that any gun used in crime be "immediately disposed of." But Bad Boy declared he had "fallen in love" with that particular weapon. He also reasoned the San Jose regiment was underarmed. So he kept the 9 mm with him, and slid it into a red sparring glove for safekeeping.

Bad Boy had done time in juvenile hall for an armed robbery, and longer stints in state prison for felony burglary and attempted murder. He was in chronic poor health, due mostly to cirrhosis of the liver, and he maintained a nasty cough; he spoke often about his death being near. While on the run, Bad Boy talked of going out "like a true soldier"--and never going back to prison.

At about 9pm Chuco, Bad Boy, Nadine and Leionna all piled into Chuco's car; they brought the red sparring glove along. Chuco drove with Nadine at his side, Bad Boy and Leionna in the backseat. The car slowed to a four-way stop before heading onto 101 near the Interstate 280 crossing.

At the stop, a police car waited. Chuco waived for the officer to go first, but the officer declined. When Chuco went through the intersection, a wave of cop cars suddenly surrounded them.

A bright light shined into the car. Chuco looked over his shoulder in the backseat at Bad Boy. "What do you want to do, bro'?"

Bad Boy: "Take off."

Chuco hit the gas pedal and made it to the freeway in a few seconds. Sirens chased him. Leionna turned and looked behind her and screamed that cops were everywhere. Someone inside the car started calling for the 9 mm gun.

On the freeway, Chuco reached 80 miles an hour. But traffic thickened, so he was forced to stray to the shoulder. Finally, the traffic clogged all lanes to a stop, so Chuco veered off to the side of the road. As the car rolled to a stop, Chuco reached over Nadine's lap, flung open the door, slid over her body and ran. Ten feet later, an officer tackled him to the ground.

The others in the car, including Bad Boy, gave no fight.

DREAMER AND BETO, MEANWHILE, were still running strong, for nearly one full month. They bounced around among family and friends, staying a few nights with Dreamer's brother, Angel, and a few nights at the home of a grandmother of a 22-year-old norteno named Rudy "Night Owl" Moreno. Night Owl's grandmother was on vacation. Dreamer and Beto kept in contact with Chuco and Bad Boy via three-ways and letters. The two kept moving.

On May 14, Dreamer, Beto and their new friend Night Owl all met at Nadine Serrano's home on Joe DiMaggio Court at about 9pm. According to testimony to the grand jury, Dreamer received a phone call from the San Mateo County Jail, a call from Bad Boy. At the end of their conversation, Dreamer pointed to Beto, who was sitting in another room, and said, "This fool is through." The filters had come down, and Beto's time had come.

Dreamer, however, told the story differently to his two friends in the house. He told Beto and Night Owl that they had just gotten a green light for a hit in the east San Jose foothills. He didn't say who. At Dreamer's direction, the three men piled into Beto's beater, a four-door white Hyundai. The backseat carried a 12-pack of Budweiser. Dreamer rode shotgun. Beto drove.

When Beto reached Mt. Pleasant Road near Higuera, Dreamer told Beto to stop the car. They'd walk the rest of the way. As the men hiked up hill, another car passed by and the driver flashed the high beams. The driver later told authorities it was unusual to see anyone walking along the shoulder of Mt. Pleasant Road, especially if wasn't a neighbor. She passed the men, and drove up the road, and turned up into her driveway.

Beto had his suspicions. He knew he blew the job by not wiping the fingerprints from the car used in the Viramontes hit, and he knew Dreamer was angry about it. And yet he told a friend he hoped that his "paperwork" validating gang membership would be showing up any day. On the way up into the hills, Beto offered to be the gunman for the hit. He said he wanted to earn his stripes.

As Beto walked ahead, Dreamer and Night Owl dropped behind, and Beto said, "But if I ever get taken out, I want it to be you, Dreamer."

Dreamer replied, "Shut the fuck up."

The driver who had passed by earlier walked down her driveway, now, back toward Mt. Pleasant Road to check her mailbox. As she walked, she heard gunshots, maybe five or six, and saw flares of reddish yellow light. Then she saw the figures of two bodies running away in the dark, back down the hill.

She returned to her house to retrieve a lantern. She ran down to the road, this time joined by her husband, and found Beto's body laying face down in the dirt; blood running downhill. Beto had been hit twice in the head and a third time in the chest. The couple called the police.

Dreamer and Night Owl ran to Beto's car, but they couldn't start it; the keys were in Beto's pocket. The two men ran through the hills, toward the flatlands of the East Side.

Beto's body fell on unincorporated county land, so the homicide investigation turned to the Santa Clara County sheriff's office.

One of the first officers on the scene was Deputy Frank Lopez.

THE NEXT AFTERNOON, Saturday, May 15, Dreamer met up with his brother Angel to pick up tuxedos. The two brothers had dates to the prom at James Lick High School. Angel had arranged the evening. His girlfriend had a younger sister, age 18, who needed a date; the two couples went dutch.

They danced at the Decathlon Club, and posed for pictures. In one, Dreamer flashes the XIV hand sign. (XIV represents the fourteenth letter in the alphabet, N, for norteno.) Later, the foursome partied in a room at the Embassy Suites. The two brothers listened to a CD, Westside Connection, to a song titled, "The Gangsta, the Killa and the Dope Dealer."

According to Dreamer's prom date, she had another suitor in mind and preferred not to go with Dreamer. "But I was afraid of hurting Angel or David's feelings," she said. She added that Dreamer didn't mention what he had done the night before.

But that night, Dreamer did make an important disclosure to Angel. He told his brother, "Beto messed up bad and had to be dealt with."

Angel later told the grand jury, "He felt bad that Beto had to be murdered but it had to be done."

DREAMER'S TIME WAS RUNNING out. After his weekend at the prom, he left Angel's house and took refuge at a residence in Milpitas. For three days, Dreamer sat in the garage getting tattoos drilled into his skin by a friend, Chris "Joker" Alvarez. In a move that would later delight police and prosecutors, Dreamer had Alvarez illustrate the last month of his life on his forearm. Alvarez inked in two skulls, both with bullet holes, representing Viramontes and Beto. Above them, in block lettering, 187. In between the skulls, a smoking gun.

Alvarez was working on another tattoo, an Oakland Raider's shield on Dreamer's midriff, when they took a break one afternoon, May 28.

Dreamer's hosts had children, who were planning to go on a field trip with their schoolmates. As a favor to his hosts, Dreamer went along to chaperone the children. He walked his young friends to the school just a few blocks away.

As the yellow school buses lined up in the parking lot and parents and children waited to board, officers swarmed in on Dreamer. The arrest, according to the mother who harbored Dreamer, was troubling for her, her child, and "the entire school."

ONE OF THE FIRST people Dreamer ran into at the Santa Rita Jail in Alameda was Anthony "Chavo" Jacobs. Jacobs' duty, as the senior NF member in the jail, was to interrogate any Northern Structure or NF member regarding the circumstances leading to his arrest. Then, Jacobs was to file a report back to his superiors in Pelican Bay.

Jacobs described Dreamer as "bragging" about the Viramontes job. Dreamer showed off his new tattoos that told the story of his wild spring. Dreamer also relayed that the first time they approached Viramontes' home, and tried to kill him, Beto was supposed to be a shooter but chickened-out as he walked to the front door. Dreamer said Viramontes' rottweiller, "Camachili," was on a leash in the front yard, barking, and Beto wouldn't shoot the dog like Dreamer demanded. Instead, Beto ran back to the car, and Dreamer had to follow him. Beto, Dreamer said, "had a tattoo on him he had no right to have. He had to prove it." The second time around, Dreamer made Beto the driver.

Dreamer added that Beto was his second choice for the job. Originally, he asked his old friend Alex, a buddy from the ESH days, but Alex declined. Declining was the act of a traitor.

Dreamer also shared news that jarred Jacobs. Dreamer said he expected to get away with the Viramontes homicide at trial because the Campbell Police Department couldn't make a case. Jacobs challenged Dreamer about how he could be certain. According to Jacobs, "[Dreamer] said he had an uncle in the Sheriff's Department, and that he was leaking information about the case." Also, "He has an uncle who was plugged in, and he [the uncle] told him they had no case. He was keeping Dreamer abreast if there was any type of activity going on toward him."

Jacobs didn't show it, but he was terrified Dreamer was telling the truth. Jacobs, unbeknownst to Dreamer or anyone else in the NF, had already turned informant for the state, and worried Dreamer's police source would blow his cover.

WITH EVERYONE BEHIND bars, and the two homicide investigations filling up the evidence room, Bad Boy offered to make himself state's evidence. In early June, two months after his arrest, Bad Boy wrote a letter to Ana Spear, a Campbell PD homicide investigator, and listed his demands: He wanted all charges dropped, and to be moved to another state. He also wanted his immediate family put into a witness relocation program. "Their lives are in danger," he wrote.

Along with information on NF, Bad Boy also offered Spear explicit details about a police officer who "had given the gang information."

"You need to understand," Bad Boy wrote, "you have a cop who's telling."

One week later, Bad Boy sent Spear another letter, this time denying he'd ever turn on NF. In yet more bizarre behavior, Bad Boy later called Spear from jail and muffled his voice in an attempt to sound like his accomplice, Antonio "Chuco" Guillen. The masked Bad Boy told Spear that his friend, Bad Boy, needed to be placed in protective custody because a death sentence had been issued.

But Bad Boy tipped his hand when he pronounced Guillen with hard L's; the real Chuco pronounced the l's silent. To confirm, Spear phoned the jail and learned Guillen was on lock down--and Bad Boy was on free time, standing at the phone bank using the telephone. The next day, an anonymous woman, who would later be linked to Bad Boy, called Spear to say she had "incriminating evidence" fingering Chuco and Dreamer--and exonerating Bad Boy.

IN FALL 1999, the Santa Clara County grand jury convened. From the NF trials in the early '90s, county district attorneys Catherine and Charles Constantinides used grand jury testimony as their best weapon to root out contradictions. Members were more likely to trip over lies and half-truths in their sworn testimony before the case ever went to trial.

Ray Lopez , Deputy Frank Lopez's son, was the first person called. He worried the NF had a hit on him; he said Dreamer's mother told him so. He hadn't spoken to Dreamer directly since the Viramontes murder, he said.

Lopez was called back a second time where, under oath, he admitted to swerving around the truth. He was testifying under stress of believing his life was in danger. A few days after the Viramontes hit, Lopez now recalled, Dreamer had reached him by phone. And he had discussed the conversation with his father.

On the stand, deputy Frank Lopez said he knew his nephew was involved in gangs but paid so little attention he had no idea if his nickname was Dreamer or Sleepy. He said he attended the family barbecue celebrating David's release in 1998, but hadn't spoken to him since.

Deputy Lopez admitted briefing the Morgan Hill Police Department and his immediate supervisor about a planned murder at the Viramontes funeral. But he also copped that he never revealed that his son, Ray, and his nephew, Angel, were his confidential sources. He never suggested his kin speak with the Campbell homicide investigators, and never suggested to investigators that he had sources who might be relevant to the case.

In fact, Sheriff's Deputy Frank Lopez didn't tell anyone in law enforcement his family might have information on the Viramontes murder until early October--five months after he believed Dreamer "may be involved in a homicide" and a good four months after Beto had been killed.

WHEN DREAMER TOOK the stand, he was not in a bragging mood. He denied knowing much, if anything, about NF. He gave screw-you answers regarding his whereabouts during the Viramontes murder.

QUESTION: On Monday, April 19, what did you do in the morning?

DREAMER: Not really too sure.

QUESTION: What did you do in the afternoon?

DREAMER: Really don't recall.

QUESTION: What did you do in the evening?

DREAMER: Not too sure.

Yet when the questioning turned to his relationship with his Uncle Frank, Dreamer flatly denied his uncle helped the gang. Then, he suggested another officer had assisted the gang's cause.

QUESTION: Did you ever tell anybody that you had a cop who was giving you information on the gang?

DREAMER: Yeah.

QUESTION: Who?

DREAMER: Who did I tell it to?

QUESTION: Yes.

DREAMER: Some of my homeboys.

QUESTION: Why did you do that?

DREAMER: Because it's true.

QUESTION: Who's the cop?

DREAMER: Can't say.

QUESTION: Why?

DREAMER: The way I am.

QUESTION: Which agency does he work for?

DREAMER: Santa Clara.

QUESTION: County?

DREAMER: Yeah.

After listening to 73 witnesses over the course of three months, the grand jury indicted Dreamer, Bad Boy, Chuco and Night Owl. In March 2000, they all pleaded guilty and accepted deals.

Dreamer and Bad Boy each were sentenced 50 years to life for acting as the trigger men, and Chuco was sentenced to 25 years.

Rudy "Night Owl" Moreno, who had never been to prison, also got 25 years.

And although Beto paid with his life for not wiping the car of fingerprints, the issue was moot. Several witnesses at the La Valencia Apartments told investigators they saw the four men sitting inside the Explorer an hour before the crime. The assassins had munched on Jack-In-The-Box fast food and dumped their trash in the parking lot. Criminologists lifted prints off soda cups, straws and lids.

![]()

Familia Affair: Nuestra Familia members and associates played out a string of gang commands that left them dead or in prison.

Familia Affair: Nuestra Familia members and associates played out a string of gang commands that left them dead or in prison.

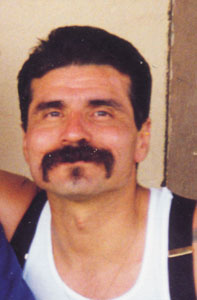

No retirement: Robert 'Brown Bob' Viramontes was a leader in the old guard of Nuestra Familia, whose changing stance on gangs cost him his life.

No retirement: Robert 'Brown Bob' Viramontes was a leader in the old guard of Nuestra Familia, whose changing stance on gangs cost him his life.