![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

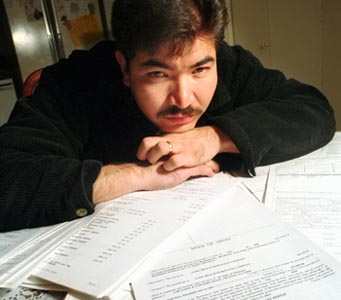

Rate Rape: First-time home buyer Alvaro Rodrigues says he signed for a loan without realizing that the interest rate would adjust upward to 15.84 percent.

Prime Victims

Offering high-cost loans to low-income communities is a booming business--especially if buyers don't read the fine print

By Dara Colwell

AS ALVARO RODRIGUEZ RECOUNTS his story, the unassuming husband and father of three smiles in disbelief--his tiny, yet beautiful house, spotless and adorned with his wife's tasteful touch, comes close to being his dream house. But the privilege, he quickly discovered, came at a great cost.

Rodriguez's story seems simple at first: his landlord wanted to move back into the house his family was renting, and with only a month's notice. Rodriguez decided the time had come to be a homeowner. He applied for two loans, one of them a $50,000 loan through a local real estate agent. He got approved, found the house and finally, during an arduous and detail-heavy process, signed a thick stack of loan agreements. Within a few hours, while flipping through the contract, Rodriguez noticed a note for a balloon payment--a puzzling term his loan supplier, The Mortgage Outlet, had failed to mention. When he questioned his real estate agent, Rodriguez learned his monthly payments would only pay off the loan's interest and not reduce the principal at all. To make matters worse, in 15 years the homeowner would have to shell out the remaining balance: $45,772.

"I had already signed and we had to move out of the place. I had no choice," Rodriguez says, exasperated. "I told my wife we had to get out of the loan as soon as we could."

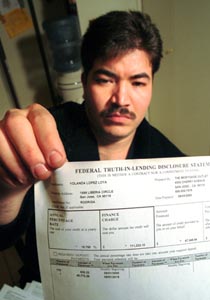

What Rodriguez also wasn't told was that the loan's proposed interest rate would adjust up to 15.84 percent--the going rate for a "C" paper loan is 9.75 percent and balloon payments typically work to lower interest rates. Rodriguez also wasn't told that a prepayment penalty fee, roughly $3,000, would be levied if he attempted to refinance the loan or sell his house. Nor was he told, he says, that he had three days to legally cancel the loan. Rodriguez's "reasonable" $50,000 loan turned out to be lousy. By the time he pays the finance charges and the balloon payment, his loan will cost him nearly $160,000.

Rodriguez fell prey to a phenomenon critics call "predatory lending" that is claiming hundreds of thousands of victims nationwide and in Santa Clara County, where housing shortages and high prices have forced many into hasty decision-making. Subprime lenders--companies such as The Money Store, WMC Mortgage Corporation, Associates and New Century--have been tremendously successful marketing high-interest loans to people, like Rodriguez, who have iffy credit. And what's worrisome is that the industry, which has attracted some of the biggest names in American finance, is on the rise. Lending to shaky borrowers skyrocketed 900 percent over the last decade, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the industry originated $150 billion in outstanding loans last year. Nationally, a disproportionate number of those loans are made in minority and low-income neighborhoods.

"It's hard getting used to the idea you're throwing your money away," Rodriguez says. "I have this loan for 15 years--I'm just throwing my money away."

Substandards

LIKE MANY WHO have been duped unsuspectingly by subprime lenders, Rodriguez felt he had few options. Often shut out of mainstream lending by redlining--the practice whereby big-name banks refuse to do business in poorer neighborhoods--minorities and low-income families are desperate for access to credit. This is where predatory lenders step in, capitalizing on the community's dearth of financial resources. According to Forbes magazine, home-equity subprime lending more than quadrupled from 1988 to 1998.

Subprime lending basically works like this: Lenders grade candidates on an A (good credit) to D (bankruptcy) scale; anyone scoring an A-minus and below is considered a potential risk and therefore rates as a subprime borrower. Greater risk translates into higher interest rates. While the going interest rate for someone with perfect credit who borrows from a mainstream bank is about 8 percent, the rate for subprime loans starts at about 9.5--though in practice those rates typically climb much higher, into the teens.

Even so, the long-term impact of a "modest" interest rate of, say, 10.5 percent can be dramatic. For example, a person with a 30-year loan at 10.5 percent interest will pay $33,000 more than an individual who takes the same loan at 8 percent.

While there is a legitimate need for subprime loans for those whose credit is not up to par, the industry is rife with predatory lenders. And it has grown dramatically, increasing by 40 percent annually since 1993. Critics like ACORN, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, the country's largest grassroots organization, has tracked the industry's practices, pointing out a slew of abusive tactics: tacking on unnecessary credit insurance, using high-pressure strategies to encourage repeated refinancing, adding extra fees and often misrepresenting the specifics of the loan.

Take, for example, Tereas Median, a San Jose woman who took out a loan from Household for $5,265 to pay off her balance with another subprime lender, Beneficial. Household tacked on $1,066 for credit insurance, including life and disability insurance--over 20 percent of the loan--at a soaring annual percentage rate of 29.6 percent. Credit insurance, which pays off the particular debt if the borrower can't, is often unnecessary and many subprime lenders like Household own subsidiaries that sell the insurance. What's more, credit insurance doesn't actually pay the borrower, it pays the lender. So the lender, ultimately, pays the insurance claim to itself.

"They're feeding on desperation," says John Eller, an organizer for ACORN's San Jose chapter. "This is a rapidly growing, billion-dollar industry with very little regulation--what their profits represent to us are more people being drawn into poor loans."

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Dirty Little Secret

THE FACES OF predatory lenders may appear to be those of con artists, but the cottage industry's backing is often legitimate, found among some of the nation's largest financial institutions. "One of the most disturbing aspects is these aren't just back-alley loan sharks," says Jordan Ash, ACORN's national researcher. "They're being financed by some of the most respected names on Wall Street."

Institutions that have direct ownership of subprime lending subsidiaries include Bank of America, which owns EquiCredit; Wells Fargo, which owns Directors Acceptance; U.S. Bank, which has ownership interest in New Century Mortgage; and Washington Mutual, which owns Long Beach Mortgage. The company came to Janet Reno's attention several years ago for practicing illegal race and sex discrimination in loan pricing.

There's also investment giant Lehman Brothers, which bankrolled First Alliance Corp., the beleaguered mortgage lending company that filed for bankruptcy last March. First Alliance garnered the attention of The New York Times and ABC News' 20/20 for concealing fees and rushing customers, many of them elderly, through a mountain of paperwork to hide costs, such as $24,700 in loan fees.

And there's Citigroup, parent to Citibank and CitiFinancial Division, a subprime lender with 1,170 branch offices nationwide. Citigroup recently acquired Associates First Capital, the nation's largest consumer lender, with assets of more than $100 billion. In October, Associates was targeted by North Carolina's Coalition for Responsible Lending as one of the country's worst predatory lenders. The group shrewdly noted that some of Citigroup's own lending practices skirted predatory standards, such as charging a 9 percent origination fee.

Even Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan has voiced his criticism over predatory lending practices, saying that the Federal Reserve is working to address the issue. But legislation to curb such practices has been slow. In California, Senate Bill 2128, which would require borrowers to see a HUD-certified loan counselor, was pulled a few days before coming to a committee hearing this fall. Proponents felt they would have had to water the bill down to get it passed.

"Everyone's recognizing it's a problem," Ash says. "But very little is actually being done about it."

Money Matters

THE EXCLUSION OF poor and minority communities from mainstream banking services has resulted in a lack of sophisticated financial knowledge crucial to making a good loan.

"One key to a person's financial stability is knowledge," says Adam Bass, senior executive vice president at Ameriquest Mortgage, based in Orange, Calif. "Knowledge can't be underestimated. Our goal is to get people to understand their loan. You can't say to someone, 'We've given you all the documents, but you can't have it.'"

Ameriquest, once a major target of ACORN's criticism, has established a new lending program with the nonprofit organization that focuses on loan counseling. Bass says he hopes ACORN's guidance will help borrowers better understand the process. "The forms required by federal and state law are complicated and voluminous--there's no question," he says. "There are abusive lenders out there. But our goal is to do the right thing."

It may be a start that's long in coming, but borrowers, who rely heavily on lending professionals to honestly guide them, may not be so lucky when it comes to the majority of subprime lenders.

Perhaps Rodriguez's words should serve as a strong warning. "Now I'm going to think twice before signing anything," he says.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Subpar: The loan received by Alvaro Rodrigues is a classic example of a so-called subprime loan, with no paydown on the principal and a balloon payment of the full balance due in 15 years.

Subpar: The loan received by Alvaro Rodrigues is a classic example of a so-called subprime loan, with no paydown on the principal and a balloon payment of the full balance due in 15 years.

From the November 30-December 6, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.