![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Crumbling Colonnade

Christopher Gardner

Residents of downtown's taxpayer-subsidized Colonnade say that the 12-year-old 'luxury' apartment building is on its way to becoming a middle-class slum

By Jim Rendon

ROB BAKER STANDS in the interior courtyard of his apartment building looking at a fountain filled with dirt. Little water spigots rise to the level of the soil, peeking out amid the freshly planted flowers like the periscopes of a buried submarine fleet. Careening to one side, a brown shrub occupies the top tier. "This once was a really nice fountain," Baker says. He looks up at the dying shrub adorning the ex-fountain's peak and laughs with a scoff. "A dead tree--that's perfect."

For Baker and other residents paying top dollar--$750 for studio apartments and $1300 to 1400 per month for one-bedroom places--to live in what was once touted as downtown's premier luxury apartment building, the defunct fountain in the fourth-floor courtyard stands as a symbol of how life has deteriorated at the Colonnade. Despite $4.6 million in redevelopment subsidies handed out to developers Goldrich and Kest and Kimball Small before the building's opening in December of 1986, one of the city's earliest redevelopment-related housing efforts has fallen into what some residents say is an intolerable state of disrepair.

"When we first moved in, we wanted our friends to come down from upstate New York," recalls 24-year-old Baker, who works for Sun Microsystems. Baker was sold on the Colonnade by the fountain, the pool, the convenient location across the street from San Jose State University where his girlfriend, Wendi Verberg, attends graduate school. Now Baker wants out. And like scores of other angry tenants, he is fearful of a cramped housing market, loath to pack boxes again and nagged by a feeling that he's been scammed. And the fountain, although a potent symbol, is actually the least of his problems.

WHEN THE Colonnade apartments opened for business in 1986, the upscale development situated on prime land between the university and the city core, was touted as the precursor to a revitalized downtown. Luxury housing such as the Colonnade, city officials said, would bring a certain cachet to having a downtown address. With scores of new residents living in the city's core, retail shopping would boom and the city would achieve its much-lusted-after 24-hour-city status. Redevelopment officials hoped people would forgo the sprawling, commuter-congested suburbs for high-end high-rise metropolitan living. The new tenants would be within walking distance of the symphony, the ballet, art museums and theaters.

In the early 1980s the city's Redevelopment Agency was anxious to add new residents to its renovated downtown, generously giving Goldrich and Kest, a Southern California developer and property manager, and its partner, Kimball Small Properties, a $4.6 million subsidy to make the project fly.

As part of the original subsidy deal, G and K agreed to give San Jose half the profits if apartments in the Colonnade ever sold as condominiums, a conversion which seemed feasible if downtown grew and prospered. Less than a year after the building opened, the Mercury News reported that security in the newly opened building was so tight that then Mayor Tom McEnery was turned away when he asked to view a model apartment.

This is a top-security building, he was told.

Now, at 5:30 as the last rays of fall light are fading, the security guard's chair is vacant, tilted up against the desk in the lobby. Copies of the Wall Street Journal and San Francisco Chronicle lie folded on the table top. Baker says security has been irregular, at best. "We already went for a week and half without a guard," Baker says. "Then we had a guy and his wife who slept on the couch all night. They never even looked at the security camera."

To make matters worse, living conditions at the Colonnade have become so bad that tenants there are threatening a class-action suit. The chances of a condominium conversion--and city payback--seem more remote with each new crack in the ceiling.

YVONNE BURNETT wasn't thinking about buying her apartment when she climbed into her shower on Oct. 10. She was wondering where all the hot water went. The building's manager couldn't provide much insight. The next day she showered at her mother's house, hoping it would be a short inconvenience. A week later, she was still standing in ice cold water. The laundry room had no hot water, either.

And Burnett was not alone. Between Oct. 5 and Oct. 28, 45 of the 220 apartments in the complex lost hot water for 10 to 12 days.

Almost 10 days into the problem Steve Barnett, a code enforcement inspector with the city of San Jose, got wind of the problem and put pressure on property owners and managers Goldrich and Kest to fix the hot water. Barnett didn't cite G and K because the problem was fixed quickly once he became involved. But he says that other issues are still under investigation, including violations of the city's housing code, and he keeps having to make trips out to the Colonnade.

By the end of October, when warm water again flowed from the tap, it was at such low pressure, residents say showering is still a challenge. Some residents, in fact, just take baths rather than hassle with the nozzle's warm drizzle. G and K offered to take 20 percent off each tenant's rent for every day they went without hot water. For Burnett, who had gone for 10 days without hot water, that meant a $50 reduction of her monthly $746.

"There is no communication [between management and tenants]," she says. "The attitude was 'Why are you complaining?' " In the seven years she's lived in the building, there have been problems, but none like she has seen since July. "The dam just broke," she says.

For the previous six-and-a-half years, she says, she was happy. She enjoyed it so much that she encouraged her sister, Loretta, to move in--a decision they both have come to regret. When Loretta Burnett showed up in August, she found the patio attached to her fourth-floor studio infested with inch-and-a-half-long roaches spewing from the drainpipe. Back in August, G and K promised to put a screen over the hole, but as of press time, nothing had been put in place to block the insects.

"It's awful. I get sick when I think about it," she says. "I never go on my balcony, ever," she says.

This summer, water leaked for six weeks next to her car. When she complained to the building's manager, a maintenance person eventually put a recycling bin under the leak. But it was rarely checked and usually overflowed. "There were huge lakes of water in the parking garage," she says.

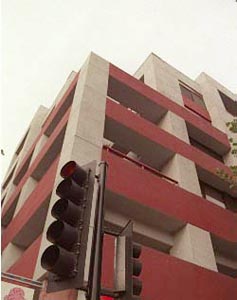

Christopher Gardner

INSIDE THE multistory garage, Baker looks up at the ceiling and begins to laugh. He points out a long meandering crack covered over with caulking. On either side of the caulk, 6-inch stalactites stretch toward the floor. "These people use caulking more than some people use duct tape," Baker scoffs. The meager repair attempt was a vain effort to stem the tide of water that dripped from the garage roof onto tenant cars. Some of it was chlorinated pool water which corroded the paint on unlucky autos.

A little farther down the row, past the bright orange rusting pipe and a corroded electrical box covered by a plastic bag, a different approach to flood control is on display. Roof gutters and sheets of corrugated metal are wired to the pipes that run across the ceiling. The purpose seems to be to route leak water from directly on top of cars to the spaces between parking spots. The haphazard gutters are everywhere.

While Baker is pointing out more cracks, Jacqueline Schumann, another tenant, carrying a load of groceries, looks at the caulking job and laughs bitterly.

Schumann moved into the building a year ago. She and her boyfriend loved to swim in the pool and use the hot tub. Now, Schumann says, neither is in working order. Just before the Fourth of July, their storage space, along with 10 others, was broken into. When she told the building manager, no one notified the rest of the tenants.

In early July when Schumann and her boyfriend were on their way to a blues festival, they found they could not get out of the garage. Power had gone out in the building, and the automatic door would not open. She went to the security guard to see if he could open the gate. The emergency key was not in the building, and the guard was reluctant to call anyone at G and K. By the time he finally got management on the phone, a line of cars was backed up through the garage. After hours of waiting, a few tenants broke the lock and held up the gates to let the cars roll out. The building's staff stood by and watched.

"Management is totally unresponsive," she says. "I felt like I was in a different country."

EVEN BARNETT, the city inspector, has had trouble with G and K. In his many trips to the building, he looked at the cracked ceilings, the hot water problems, the leaky roof, and he talked with a dozen tenants, all of whom have significant problems. "I have been surprised as far as the response [of the building managers]," he says. "It hasn't been to my satisfaction personally and certainly not to the residents' satisfaction. It is somewhat disconcerting," he says.

Goldrich and Kest is no stranger to the city--or its subsidies. In addition to the $4.6 million the company received to put up the Colonnade, they received another $12.5 million subsidy to build the Paseo Plaza Condominiums just down the street from the Colonnade. In 1996, the Redevelopment Agency made an emergency $10 million loan to Goldrich and Kest so they could continue building the condominiums. Sales in the first phase of the project had been slower than expected.

G and K, based in Culver City, is a property giant. They own 151 apartment buildings with a total of almost 17,000 units. The vast majority, 130 of those buildings, are government-subsidized low-income housing. In San Jose, G and K owns seven apartment buildings, three of which company representatives says are low-income properties.

Three more buildings used to be low-income properties. Blossom Hill, Village Green and Lawrence Road apartments used to cater to low-income tenants because of agreements made between G and K and the federal government. The company received subsidies to build low-income housing. But when a 1996 law allowed landlords to bring rents up to market rate, G and K acted quickly.

Larry Boales, a senior rental dispute analyst with the city of San Jose, says that while many of the residents were able to retain their housing, the government is paying for G and K's rent increase. At Blossom Hill, many tenants had complaints similar to Baker's and the other Colonnade tenants'. "Maintenance problems were a major feature of [landlord-tenant] negotiations," says Boales.

Ansel Romero, who is in charge of the Colonnade apartments for G and K, did not return phone calls. Calls to G and K's main office in Culver City were also not returned.

In his fourth-floor apartment, looking out onto the dirt-filled fountain, Baker gets riled when he talks about G and K. He brings out photographs of a spore-covered wall that was revealed by repairmen working on a leaky shower pipe. Damage was so extensive that the whole tub was removed, but the mold-covered wall was left behind. It took 24 days for him to get a new working shower. In the meantime the mold caused rashes on his legs and exacerbated his girlfriend's asthma. He says he was told to withhold his rent until he reached an agreement with G and K and then digs through a pile of papers to reveal an eviction notice. "I'm taking them to small claims court," he says. Baker, like so many other tenants, has had enough.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

High-rising Tales: Tenants at the Colonnade apartments are angry over various housing problems--including cracked ceilings, a leaky roof, plumbing malfunctions and insect infestations--and they're threatening to vent their wrath in a class-action suit.

High-rising Tales: Tenants at the Colonnade apartments are angry over various housing problems--including cracked ceilings, a leaky roof, plumbing malfunctions and insect infestations--and they're threatening to vent their wrath in a class-action suit. Water Proof: Drainpipes in the Colonnade parking garage show evidence of leakage.

Water Proof: Drainpipes in the Colonnade parking garage show evidence of leakage.

From the December 3-9, 1998 issue of Metro.