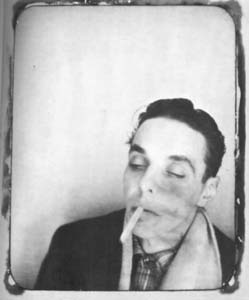

A Writer's Life: Herbert Huncke in 1940.

Herbert Huncke, the unsung Beat, finally gets his due

By Harvey Pekar

BEFORE Jack Kerouac, before Allen Ginsberg, there was ... Herbert Huncke? Though born a year after William Burroughs, Huncke (1915-1996) had been living an underground life as a junkie, thief and homosexual long before Burroughs became part of the New York Beat scene. Indeed, if you believe Huncke, he was even a sort of mentor to the author of Naked Lunch.

Such better-known Beats as Burroughs, Ginsberg, Kerouac and Neal Cassady all make references to Huncke in their works--with good reason. Although Huncke directed a great deal of his attention to obtaining narcotics and sex (resulting in his incarceration off and on for years), he also devoted considerable attention to writing.

Huncke wrote for catharsis but had serious literary ambitions as well, although it isn't made clear in this new volume of his works how he became interested in literature, since he dropped out of high school in his sophomore year. Several volumes of his writings had been published prior to his death, but The Herbert Huncke Reader is a convenient one-stop compendium of a large chunk of his output, including Huncke's Journal, The Evening Sun Turned Crimson, Guilty of Everything and some previously uncollected material.

Huncke's output consists of short, mostly autobiographical pieces that deserve attention for aesthetic as well as historical and sociological reasons. Huncke, who led a life that had much in common with Jean Genet's, developed an original style that combined rather formal and colloquial elements reflecting both his middle-class Chicago background and his later days as a Bohemian.

In addition to writing direct, straight-ahead prose, Huncke often experimented with fragmented automatic-writing techniques:

- Easter Sunday morning--not quite daylight--a large moon rides the sky since early yesterday evening--first a soft glowing spot of white cloud--later--clouds gray moving--breaking into lacelike patterns--the moon--silver and moonlight--into the hours after midnight ...

Though he went on the road at the age of 12, Huncke was a competent technician and lyrical, evocative writer. He was given to making wry observations and registering complaints about his mistreatment by others, but he also took advantage of, and even stole from, his friends.

Often, however, Huncke was quite helpful and sympathetic to others. Benjamin Schafer, the book's editor, includes in his afterword a touching account of how Huncke aided him during a bleak period in his life. Huncke hated 9-to-5 restraints and sacrificed much to escape them, including, ironically, his freedom, spending a great deal of time in one of the most restricted environments of all: prison.

Few men who engaged in hustling and criminal behavior had his vivid powers of description. Huncke provides colorful, if grim, accounts of Bohemians living on the edge, of the difficulties they face and of their attempts to cope with them.

At times, the grimness turned to genuine despair. Busted just after getting out of jail, Huncke contemplated suicide:

- I wanted to kill myself. Thoughts of disgust, anger, frustration, confusion, and a complete physical let-down had me exhausted. At one point, I promised myself I'd do this bit and when I'd get out, I'd disappear down at the Bowery--anywhere--never show my face to my friends again, sort of fade into nothingness.

But Huncke did not give in; maybe the writing kept him from fading away. He even managed to stay more or less within the law in the 1960s and, partly due to his charm as a storyteller, cultivated a following as a writer and "character." At the end of his life, the Grateful Dead paid his rent at the Chelsea Hotel, and he lectured at colleges. Huncke, one of the fathers of the Beat movement, survived almost all his literary compatriots, living to a ripe old age in the process.

The Herbert Huncke Reader; edited by Benjamin G. Schafer; Morrow; $24 cloth.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)