![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Drive-By Hacker: Eric Berls makes his living assessing his clients' network security, usually in the areas around their buildings. For fun, he scouts the rest of the world. In the Air Tonight All it takes is a laptop, a Pringles can, a WiFi card and some shareware, and you could be on the Internet from your car for free By Traci Vogel FIFTY MILES per hour is not the optimum speed for the guerrilla activity we're involved in, but Erik Berls can't resist occasionally punching his 1999 TransAm Firehawk to fly by the strip mall gawkers along El Camino Real. "It's best to cruise along at 30-35 miles per hour--fast enough to move through LANs but slow enough to pick up signals," Berls shouts back at me. He's 29 and kind of looks like Jerry Seinfeld--that is, I imagine, if Seinfeld were a computer geek. I'm crouched in the TransAm's tiny back seat ("a 'back seat' for insurance purposes only," Berls grins), peering over Berls' shifting arm into the screen of a Dell laptop, which is filled with a growing list of strange names, numbers and plus signs. As Berls slows to cross a set of train tracks, I read off some of the mysterious names coming up on the screen: WendyNet, Rory's Air, Foxhole, Silky, Penthouse ... Surfnsip. "Surf and Sip," nods Berls. "That's the chain of cafes where you pay a fee to gain access to their wireless network." He glances at the screen. "They have WEP [Wired Equivalent Privacy], which makes the network more difficult to access." "But not impossible?" I ask. "The crypto community believes that WEP really isn't secure," Berls says. "It's better than nothing, but not really. It's like a rice-paper door instead of no door."

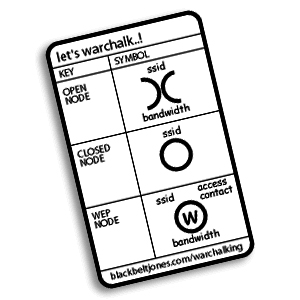

Enter the Rice Paper What Erik Berls and I are doing is called wardriving, a term coined by computer-security consultant (and Berls' decade-long acquaintance) Peter Shipley of Berkeley to describe using a laptop-and-antenna setup to "sniff" wireless networks from the street. While Shipley wasn't the first person to roam around with a laptop looking for wireless, he was the first to automate logging the activity via software and a GPS. In the fall of 200, Shipley undertook an 18-month wardriving survey that was the first to prove that the increasing popularity of wireless networks had taken computer security back 10 years. A multidirectional antenna (in the early days, it was a mono-directional antenna, a.k.a. a Pringles can or a coffee can) picks up the signal, and a UNIX-based software program reads the network's ID--like the names I listed off--and indicates the strength of the signal and, most importantly, tells whether or not the network is secured. If it's not, conceivably anyone with a 802.11a, b or g wireless--or WiFi-enabled--PC, laptop or hand-held could access it, using that network's broadband to surf the Internet for free (the number letter combinations of 802.xx refer to wavelength frequency). Wardriving has been a growing underground hobby of sorts with hackers for the past two years--and a useful tool for security analysts like Erik Berls for just about as long. The term is inspired by "wardialing," or what Matthew Broderick in 1983's now geek-classic movie War Games was doing when he set his modem to dial up successive telephone numbers in a random attempt to gain network access (and nearly destroying the world in the process, with typical Hollywood hysteria). Regional wardrives organized to chart an area's wireless networks, such as the one that took place in New York just last month, have drawn enough attention to security loopholes to make them positively notorious--and yet the loopholes continue to exist. As more and more companies and individuals set up wireless networks, issues of security and bandwidth are becoming more pressing. And the culture centered around WiFi continues to grow. Wardriving, aside from being a hobby and a useful tool, has inspired its own how-to websites, newsgroups, access-point maps, T-shirts, bumper stickers--and even its own alphabet. The alphabet, made up of symbols that can be posted or chalked on sidewalks to indicate nearby available wireless access, and even what kind it is (open node, closed node, WEP node), is inspired by old-time hobo hieroglyphics, which creative itinerants used to mark a house as friendly, or a good sleeping place, or a place where you could get handouts. Marking wireless access points in chalk is, naturally, called warchalking, and the fact that this activity is hobo-inspired is a good indication of just how grassroots the whole wireless-access community is. Unless, of course, you're a corporation, putting out a pool of wireless broadband you don't exactly want to share with others. Just as in the early days of the Internet--well, the early days of any big utility, really--there is an ideological split taking place here. Will the wireless broadband that now hovers, invisibly prolific, throughout the Bay Area and other major cities be allowed to be literally broad, available to everyone, or will it be regulated and parceled out in corporate pay-for-access packets? Many self-organized community networks aren't waiting for the inevitable: SBAY Wireless Network calls itself "a platform for wireless experimentation and a forum for wireless experimenters in the South Bay area." Since 1998, SBAY has been quietly and methodically researching sites where its members can build repeaters--towers to broadcast network hosts. SBAY now has two repeaters, one on Montebello Ridge in Cupertino and one in the Los Gatos hills, and more are planned. The futuristic dream of community network groups like SBAY and BAWUG (Bay Area Wireless Users Group, based in San Francisco), and more wide-ranging Internet associations such as the aggressively named WirelessAnarchy.com, is a seamless worldwide network of unregulated bandwidth, an endless sea of access, no matter where you are. Or, to cop from its website: "WirelessAnarchy is about creating your own long-range infrastructure, without having to pay anyone or jump through government hoops. Cheaply and easily, using off-the-shelf equipment and a little ingenuity, you too can create your own net. It's wireless, it's anarchy, it's your ISP's worst nightmare." Yes, you can be sure the big companies will have something to say about this.

Even the Nuns Love WiFi In fact, you know something is really big when competing corporations actually team up to address it, just as Intel, IBM and AT&T are doing in a joint project revealed, so far, to the public only by the code name Project Rainbow. According to the Nov. 18 New York Times, Project Rainbow's overarching goal is to "create a WiFi-based network of networks in metropolitan areas across the nation." If they succeed, the muscle in their grip on cities may be irresistible. Project Rainbow would be a communications giant on the scale of old Ma Bell, able to undersell smaller companies and control regulations. Along with Surf and Sip, the wireless cafe chain Erik Berls' system sniffed, small local company Boingo Wireless is looking to compete in the nationwide network of WiFi hot spots, which subscribers could access on the go. Boingo hopes to follow up on the success of another local company, Wayport, which currently supplies wireless connectivity service for the Norman Y. Mineta San Jose International Airport. On its website, Boingo reports that its focus groups have determined that "since SF International has no WiFi network" but San Jose's airport does, "97 out of 100 businesspeople polled said they would fly through San Jose if they can." And then there's Cisco's Aironet system, wireless network cards that have been around for so long they're positively old-school by now. To prove how user-friendly its system is, Cisco loves to trot out the nuns at Mission San Jose, whom Cisco supplied with a missionwide access system. According to one Cisco press release, the mission now has approximately 50 personal computer stations equipped with "Cisco Aironet 340 Series wireless PCI adapter cards and 12 laptops equipped with Cisco Aironet 340 Series wireless client adapter cards." "Our antennae are set up so that laptops can be used on our patios," says Sister Deborah Marie. "It would not be uncommon to find one of our sisters outdoors meditating while another is going online nearby." It's a lovely image, if a little dissonant to some who think wireless connectivity should be a God-given utility. Or, at least, that Wireless Internet Service Providers (WISPs) should not be allowed to dictate how many people you can share your broadband with (or whether you can share it at all). This is the age-old socialist impulse vs. free-market land grab, and it promises to play out over the next couple of years right here in our own backyard battlefield. No doubt, it'll be one of those battles where all the publicity will go to the four-star Cisco generals, while the real blood is being pumped by the little LAN-lord.

Elements of War Which is maybe why wardriving with Erik Berls seems so exhilarating. (That, or it could be the TransAm's horsepower.) The sky is clouded as we move past San Jose State University and toward Adobe. I find myself leaning eagerly to catch any Adobe network IDs on the screen. Why do I care? I'm not a hacker. I don't hate Adobe. If I want to surf the Internet at no cost, I can head back to work. But there's something about anonymously cruising by a company, or an individual, and catching a glimpse of its existence through invisible means that is just so cool. Wardriving's guerrilla appeal moves beyond hacker status, because to be a hacker you not only have to acquire truly arcane skills, you have to enjoy sitting in front of a computer, legendarily in some dark basement, for hours on end, eating day-old pizza. Wardriving, on the other hand, is like a road trip where you get to take the Internet with you. You might even, if you were brazen enough, actually connect to one of the networks your setup is sniffing--which Berls, for the record, is not interested in. It wouldn't be illegal, exactly--that is, the legal aspects of it are cloudy--but wardriving isn't about cracking networks. It's about logging. And logging is most definitely legal, as the website www.wardrivingisnotacrime.com explains. As we head northeast, Berls describes in general terms how the security consulting company he works for operates. The company, Farm9, gets hired by a company executive to covertly evaluate how well the company's Information System managers are securing the network. "This is where reams of 'hold harmless' paperwork get signed," Berls says. Berls and a partner spend time wardriving around the perimeter of said company--often through corporate parking lots--seeing if they can get access, or "penetrate". No one other than the hiring executive knows what they're doing, so it can get a little sticky. When a security van shows up in Berls' rear-view mirror, he sometimes has to evade certain questions. "I don't get paid to answer questions," as he says. "I get paid to make pretty graphs." These graphs indicate just how far the company's wireless network is seeping into the wider world--and where. After driving around during the day, a mapping team will often return at night, when it is less conspicuous, to get more careful GPS readings. Sometimes, such security runs produce more information than the teams bargained for. "One client, we also found, was not shredding things they should have been shredding--like financial reports that hadn't been released yet," Berls says. Then he smiles. "At that client, we also managed to snag the magnetic tag on the side of their security van." Unfortunately, Berls didn't get to be there in person when the tag was returned to the CEO. The imagined scene makes me ask Berls just how IS (Information Systems) managers generally react to the news that their system has been cracked and that they are potentially providing broadband for sidewalk users. Are they embarrassed? Pissed off? "Actually, they're usually just surprised," Berls says. "Some of them have had difficulty providing wireless connections for people inside the building--people who want to hook up in their cubicles--so they don't even consider the access outside." Wireless connectivity does not a uniform signal make. It's clumpy, and the signal can get blocked by something as flimsy as a cubicle wall. Moreover, the signal can bounce off of buildings--Erik tells a story about how, during a wardriving run for one company, his team kept picking up a signal that seemed to be emanating from the company's building but didn't match up to any of the company's ID names. "We thought maybe someone in the company had set up an unauthorized system. But it turned out the signal was from the company across the street, and it was bouncing off the front of the building." Such weirdness is sure to grow, as more and more users fight for broadband. In the same way that radio wavelengths have been divvied up, broadband will have to be. To make matters more complicated, cordless phones and microwaves operate on the same frequency as WiFi. Berls has a friend whose at-home wireless network works just great--until a neighbor picks up his cordless phone. Let the elbow jabbing begin.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the December 5-11, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.