Whose Blues Are They?

Photo by Christopher Gardner

How the music born of African-American heartbeats and sorrows has ended up in the white spotlight

By Jesse Douglas Allen-Taylor

SATURDAY NIGHT in San Jose, and it's Blues night, and the joint is jumping. We can hear JC and the Bluz Crew all the way from the parking lot as we drive up. Guitar-slapping and harmonica-wailing and somebody's barrelhousing up and down the keyboard.

Who said Blues music is supposed to be slow and mournful? We're here to chase those blue demons away, not to curl up in a big old ball and die. My date is already snapping her fingers as she gets out of the car. It's Saturday night, Blues night, and we're set for a rocking good time.

We don't get to have one. When we walk in the door of the club, all eyes turn to us. Nobody is staring, but nobody looks away, either. I try to read the crowd to see where the danger lies, but I'm way out of my element, so I can't sort out the signals. It's not my kind of crowd. It's biker-looking, all tattooed and tough, a "somebody gonna do somebody wrong" crowd.

All I can see are blank faces with blank, flat eyes. No anger--no, not that I can see--but an unsettled uneasiness, as if the question is being whispered in many ears, simultaneously, "Why are they here?" We weave our way through dancers and drinkers to the bar, trying to find a place to be inconspicuous.

There is no such place. Not for us. Not here. Saturday night at Almaden's Feed and Fuel in San Jose, Blues night, and we are the only African-Americans in the club.

We don't stay long. There is no one to blame, of course; no one in the club said a harsh word to us at all. But it was Saturday night. Blues night. It should have been our night. And on the long drive back home, I wonder, how it is possible for African-Americans to feel like strangers in a place where African-American music is being celebrated.

After all, whose Blues are they, anyway? If you had asked this question 30 years ago, there would have been no doubt about the answer. Blues music was born in the black Deep South communities near the turn of the century and for some 50 years served both as African-America's folk and popular music. In its classic form, early Blues music was often played in the 12-bar format, and told the mournful chroniclings of sad situations in the personal lives of African-Americans:

Clare Morris, "I Staggered in My Sleep"

But more often, the Blues was lively, up-tempo music you could dance the night away with, music you could dance the blues away with.

During its first 50 years, Blues music was virtually unknown to white people outside of the Deep South. Such African-American music genres as jazz, ragtime and bebop made their way to white audiences in one modified form or another. But early Blues music resisted modification and, in its raw form, was too earthy, too African, too sexual and, therefore, too frightening for the white community. Hearing an early Blues song, white community leaders would get that uneasy look the white explorers always get in the movies when they hear the "natives" beating on their drums all night.

And so, Blues music stayed a secret to the rest of the nation, nurtured and hidden within the African-American community.

But then Blues music went out of fashion, and seems to have been virtually abandoned by black audiences and musicians somewhere at the beginning of the 1960s. African-American Blues musicians languished in obscurity and sometimes poverty for many years, and the music itself was almost lost as a living art.

Guarding a Genre: June Stanley, owner-operator of JJ's Blues, hopes to keep interest in the music alive by providing a forum for Blues artists.

June Stanley, the white owner-operator of San Jose's JJ's Blues Club, thinks that African-American audiences gave up Blues music because it contains painful reminders of difficult times in African-American history.

"There are a few black people who come out and support the music, but not like it should be," Stanley says. "I can only tell you what they've told me, that they thought it was sad music. It made them think about the things that they went through."

JJ's is by far the most popular Blues venue in the San Jose area. In the past, the club had no trouble drawing African-American crowds when it brought in the big-name stars: Junior Wells, Clarence Carter, Bobby Blue Bland. But in the absence of such headliners, African-American attendance can be sparse.

A selective guide to finding the

Blues Yonder

STANLEY DID NOT just pick up on the Blues recently. Her love of the music comes from her late father, who played it on the saxophone and the banjo during the Depression years back in his native Oklahoma. Without knowing it, the elder Stanley might have played somewhere along the way with a young and then-unknown African-American Blues singer/ composer, Lowell Fulson.

According to Fulson, who is also from Oklahoma, it wasn't unusual to see whites as far back as the 1930s trying to play Blues music alongside African-American musicians in the segregated South. "Back home, we'd have these picnics and everybody would come, white and black," Fulson says. "We'd put up a big platform out in the field and start singing. And some of them whites would come and play them fiddles and them banjos right along with us."

Asked if the white musicians were any good, Fulson says, "Yeah, they could play." Asked if they could sing, too, Fulson laughs and hedges. "Well," he finally says, "they had some problems trying to sing the Blues, so I think they put a little extra time into learning how to play them."

Eventually, white artists learned how to sing the Blues, too--at least well enough to start performing and cutting records. Sixties rockers like Janis Joplin and Eric Clapton made it an important part of their repertoire, and '60s white rock audiences packed venues like the Fillmore in San Francisco to see shows with the old-time Blues singers and players.

By the 1980s, a full-scale revival was in place, with white audiences dominating practically every Blues venue, white consumer dollars creating a growing mini-market in the compact-disc reissue of classic Blues recordings, and young, white Blues musicians driving the future direction of the music.

African-American Blues artists who survived the lean years--people like Fulson, B.B. King and John Lee Hooker--are icons of the genre, worshipped at every turn, but one watches their every public performance with the sad feeling that their time is past, and that there is no line of young African-American musicians waiting to take their place.

San Jose native Chris Cain, who at 41 is one of the few relatively young African-American musicians to take up the Blues, has mixed feelings about this trend.

"Part of me says it's great that some white cats are playing the Blues, because otherwise it would be dead," he tells me. But he worries about the effects on the music itself. "I mean, you've got the inventors of the music suddenly not playing it. And the cats who got hold of it now ... 20 years down the road, is the music going to be super watered-down? Is it going to be technically different? It will be like the actual trunk of the tree being replaced by some kind of feeding tube or something. So there's, like, two voices in my head about this."

Photo by Christopher Gardner

Dogged by Elvis

SO, IF African-Americans abandoned Blues music and white people resurrected it, shouldn't African-Americans be grateful, or, if not grateful, at least be quiet about it? Well, Johnny Otis isn't grateful, and he isn't quiet, and he doesn't think that the white adoption of Blues music was all that benevolent.

"Oh, it's just another fad that white society has grabbed," he says in a voice raspy from years of singing for a living. "Whites get really angry when I say that theirs is an artificial copy of Blues music. They want to be seen as creators. Some of them are pretty good, but still, they're all interpreters. And in the end, they'll do to the music what they always do. They'll rip it off. Sooner or later, some of these kids are going to start taking bows like they invented it."

Raised in Berkeley in the Depression, Otis played and sang as a teenager in the Bay Area's black honky-tonk circuit. Later, singing, composing and leading his own band, he helped make the transition between Blues music and the more up-tempo Rhythm & Blues sound that replaced it as the popular black dance music in the '50s. His composition "Willie and the Hand Jive" is an R&B classic.

If anyone has the right to criticize the way white people involved themselves in Blues music, it is Otis. Especially because Otis himself is white. Or, at any rate, he started off as white. "When I was a little boy, I decided to become black," the child of Greek immigrants says matter-of-factly, as if he were just talking about dyeing his blond hair black (which he did). "I did it because I liked that way of life. And why not? From a very early age, I preferred the company of my black buddies."

Otis seems to have never looked back in longing to his white heritage. Growing up, he hung around the East Bay's African-American communities until he had absorbed their rhythms. He married his African-American childhood sweetheart, sought work on the railroads as a Pullman Porter, of all things (a menial, servant-type job reserved almost exclusively for blacks), and played the segregated club circuit when he could have easily made a fortune performing black music in the white clubs, a la Benny Goodman or the Dorseys.

Otis' life provides a textbook example of what a white musician might do to "play the Blues by living the Blues." He learned to play music in the same way that African-American musicians do--matching it to the beat of the quiet, African drumming of their hearts. And because of this, Otis' music is indistinguishable from African-American music, a feat rarely accomplished by other white musicians until the synthesization/homogenization of black music that began in the '70s.

Otis was also part of the infamous "Hound Dog" affair, a good illustration of why he retains his bitterness against the white music industry.

"You Ain't Nothing but a Hound Dog" was co-written in the early '50s by Otis and originally recorded by Big Mama Thornton, a singer in Otis' band. Few whites heard the song; at the time, Blues and R&B music were not played on white radio stations. But a group of record producers heard the song and wanted it for Elvis Presley, whom they were grooming to be the American musical money-making dream: a white boy who could sing like a black man.

Unbeknownst to Otis, they bought out the rights to the song from his white co-writer. Otis never saw a dime from the Presley "Hound Dog" project, which sold and made millions.

But before Presley could record "Hound Dog," it had to be cleaned up and sanitized for a white audience. Originally, Big Mama Thornton sang:

African-American Blues audiences of the '50s had no problem with such unashamed and enthusiastic sexual references in the lyrics; they relied on cleverness and innuendo, which were more designed to provoke humor than titillation, and rarely seem offensive or smutty. Perhaps this is an old echo back to the African religious beliefs that the African captives brought to this country. In these pre-Christian religious beliefs, sex is not dirty or sinful but a normal, necessary part of human life, to be celebrated rather than hidden.

But the Christian religion of the European population in America did believe that sex was sinful, and white parents would have been aghast if their children had been allowed to listen to sexually suggestive lyrics. When Presley finally got around to singing "Hound Dog" to white audiences, all meaning was drained from the words:

I remember hearing the song when it was originally released in the '50s, and wondering what the hell Presley was talking about. I still don't know.

The changing of the lyrics did not stem the Christian-backed attack against Presley and his rock & roll buddies. White fathers and mothers did not want their children exposed to and corrupted by the raging sexuality that they associated with Africa and African-America.

White-performed rock & roll was only a thinly disguised imitation of black-performed Blues and R&B. In the muscular, unashamed racism of the day, it was condemned as "jungle music" in white churches across the country--to little or no effect. The modified "jungle beat" of rock & roll swept through the white community like an elephant stampede, carrying all subsequent American music along with it.

Photo by Christopher Gardner

Heart Beats

KAMAU SEITU knows a good deal about this "jungle beat." He is a drummer. "The beat is all about people dancing," he says. "The drummer has to understand dance. He's got to be a dancer himself, or else he's just playing with sticks. He's not playing a beat."

Beat and music are an integral part of an interview with the New Orleans native Seitu. He sings (or attempts it, anyway; singing is not his forte). He claps out rhythms or drums them with his fingers on the table. He draws scales and chord changes on paper bags pulled out of the trash.

An evening talking with Seitu at his West Oakland house is like a semester with the high school band teacher you always wanted but never had. You begin to understand the internal structure of the music--what makes it all hang together. It is the beat.

"The drum was banned by the slavemasters because they thought Africans would use it to communicate," Seitu says. "So our bodies took the drum's place. We carried the beat in our voices or tapped it out with our feet or clapped it. But the beat never stopped."

Seitu denies that African-Americans have abandoned Blues music. "All modern African-American music is based upon the Blues," he says. "It's the foundation. It's the heart of all jazz; everything you hear that's jazz, it's really just a complicated form of Blues music."

According to Seitu, "We didn't give up on Blues. ... We just changed it as we went along ... into Rhythm & Blues, and then into soul (but that was really a marketing thing), and the Motown Sound, and then disco, and hip hop, and now even rap, even though a lot of the young people might not understand that. But the Blues was about African-Americans speaking about what we were going through. And isn't that rap?"

Seitu's last comment speaks to the word content of Blues music, but what about the musical content? If all modern African-American music is Blues, how can one tell exactly what Blues music itself is?

"It's a combination of European and African music," Seitu explains. He is back with his pencil, drawing harmonic scales. "Look, all of the music of the world is built upon the pentatonic scale, the five-note scale. Everybody knows it as the black keys on the piano. African music is based on the pentatonic scale. Indonesian music. And Chinese music. All of the music of the world ... except for European music. That's built on the seven-note diatonic scale; the white keys on the piano.

"So when African-American people started making up songs after they came here, they would make them up using the new scale they were hearing: the diatonic scale. But they would use the African rhythm patterns, which you'd never heard in European music.

"And the melody and the words, it was about this great pain they were feeling, the pain of racism and slavery. It was about black people's pain. I don't know, man, something about that combination, it was explosive. And that was the Blues."

Can white people play the Blues? I ask him. "It's not the fact I'm saying that white people can't play the Blues," he responds. "Anybody can play the Blues. But in order to play it, you've got to feel it. It's not just about playing a lot of notes. And I'm not saying that the white musicians who are playing this music today caused us to have the Blues. But their ancestors caused that music to come about. They gave us the Blues. So something about it, it just doesn't feel right. Not to me."

True Blues

BO KNOWS the beat. And so does Brenda Boykin. Boykin has her drummer doing the "Bo Diddley beat" all by himself, and it's got everybody's attention. We're at Ivy's Tea Room in Albany, just north of Berkeley, and it's one of the more integrated Blues crowds you'll see these days.

Big-breasted, big-hipped and big-voiced, the enthusiastic singer/ composer Boykin is a throwback to the old "big, black Blues mama," a hint of what Bessie Smith or Ma Rainey must have been like in person. She can "bring it." Her songs have already exhausted half of the crowd on the dance floor. They're ready for more, but first she's got a lesson to teach.

The drummer keeps on with the "Bo Diddley beat." Everybody's beginning to shake something or tap something or stomp on something to try to keep time to it. It's a standard rock & roll, R&B beat. You can hear it on Johnny Otis' "Willie and the Hand Jive" or Smokey Robinson and the Miracles' "Mickey's Monkey." Three taps in a row, then a pause, then two more, all just a little off-beat.

This is a dance beat. This isn't a beat that drives you to rage and bad actions, as rap or hard rock so often do; this is a beat that just makes you want to be silly. It makes you want to have fun. It is also one of the oldest beats in the world.

Boykin gives us a quick history lesson. The "Bo Diddley beat" originated in West Africa, where it is still played. It traveled to the Caribbean in modified form under the name of "clave" and became the underpinning of all Afro-Latin music: the mambos, the rumbas, the cha chas.

The great Blues guitarist and singer Bo Diddley heard it growing up in the South and incorporated it into his songs and recordings, which Boykin describes as some of the most African-sounding music of the Blues genre, "like what a native West African would play if he sat down to compose a Blues song."

Talking to Oakland-born Boykin some days later, I ask her how the white adoption of Blues has changed the music.

"The way the old African-Americans did the Blues, they never did a song the same way twice," she says. "Each time, it was sung or played according to the way they felt that day, or at that moment. African-American music has that kind of fluidity to it. It allows for that kind of innovation."

But, she adds, "Let's say a folklorist came along with his recorder on a particular day, and recorded some old Blues guitarist, and he played it the one way in a thousand ways that he had done this song. Seventy-five years later, one of these white 'Blues purists' gets the recording and gets out his guitar and starts playing it exactly the way he hears it, note for note, chord change for chord change.

"He'll do it the same way, over and over, every time. And he'll insist that this one particular way is the only 'authentic' way that the song can be played; these same guitar licks, in this same particular key. But that's not the way the music was intended to be."

Boykin says this is where you're going to lose a young African-American musician. "We are people that are creative and moving forward," she says. "So even if a young black man loves the Blues, believe me, he's going to learn that old music, dig it and figure out a way to make his own thing. And he may know the same information and learn the history and do exactly the same thing as the white 'Blues purist.' But because this black musician owns the music ancestrally--this is the positive--he's not going to stay there and imitate that forever. The way African-Americans tend to do our music, we invent the art form, master it, enjoy it and move on. Like, say, someone like Jimi Hendrix did. There's not a whole lot of moving back."

Boykin explains that she used to have "an attitude" toward these "Blues purists," calling them by the more derisive name "Blues Nazis." Now she thinks they are part of a "necessary process."

"What's positive about these people," she admits, "is that because of their love of the music, they know their Blues history backward and forward in a way most African-American musicians don't. We don't always have the time to do all of the studying. We don't always have the money to buy up all of the records. So they have a lot to teach us."

A Deeper Chord

WE ARE BACK at Ivy's, still dancing to the "Bo Diddley beat," still dancing to the same beat that people danced to in a clearing in an African forest at humanity's dawn. It is an epiphany--a connection. I have been around the Blues all of my life. One of my earliest memories of my father is his listening to Ray Charles records on late Sunday afternoons, the only time he ever got a break from work. For me, in later life, listening to the Blues has always helped connect me with home, and family and race.

But Boykin has sung a deeper chord, giving me a connection with my ancestral homeland. It is difficult to completely absorb. How can one think of early humans as being "nasty and brutish" if they were dancing around to the "Bo Diddley beat" and doing an early version of the hand jive? I laugh out loud at the thought, as one of those first folks must have laughed out loud.

Did African-Americans abandon the Blues? No, because the essence of Blues is the beat, and we have never abandoned the beat. We have heard and followed the drummer's beat all of our lives. It is still there, always, a comforting guide to the rhythm of our lives. It connects us to places we do not even know we have been. We carry the beat with us always, pressed between our middle finger and our thumb, a tremendous energy waiting only to be released, waiting only to explode.

And who owns the beat?

Nobody. Or everybody. The beat is not racial--it's human. It is the meter of the human heart. Black people had it, and kept it. White people once had it, I think, and lost it, though I am not sure how. But the loss is cultural, I believe, not genetic.

Some find it again if they live the life, like Johnny Otis. Some find it by closing their eyes, holding their breath and listening to their hearts. It is out on the dance floor, but you can't fight it. You cannot talk your way into the beat; you cannot reason your way in. And you damn sure can't beat the beat. You've got to just go by the feel of it, and that's that.

So whose Blues are they?

In a way, the question seems moot. The Blues we see now are just artifacts, the discarded shells of creatures long since moved on.

Walter "Slatt" Parker, "Cretaceous Blues"

Somebody give me a guitar lick, please. And a beat. I need a beat. We're going to go someplace with this.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Channeling Ma Rainey: Singer Brenda Boykin traces the Blues beat from West Africa to the American South by way of the Caribbean.

When I ain't got no liquor,

Look like everything I do go wrong

That's when I get evil.

Me and the devil can't get along.

Christopher Gardner![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

best Blues around the Bay.![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Bluesman Mamou performs at JJ's Blues Club.

You ain't nothing but a hound dog

Just snooping round my door

You can wag your tail

But I ain't feeding you no more.

You ain't nothing but a hound dog

Crying all the time

You never caught a rabbit

And you ain't no friend of mine.

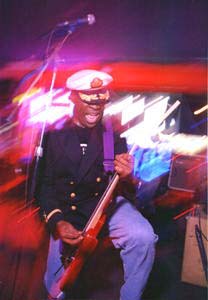

The Spirit of the Beat: Kamau Seitu keeps time with his band at San Francisco's Les Joulins club.

My Blues was like the dinosaurs, or this is what I heard

Ain't nothing happened to them, boss, they just turned into a bird

So you can tarry round here long as you like, but I ain't gonna stay

I'm gonna go out and follow my Blues, cause they done up and flewed away.

From the December 5-11, 1996 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)