Justice Murdered

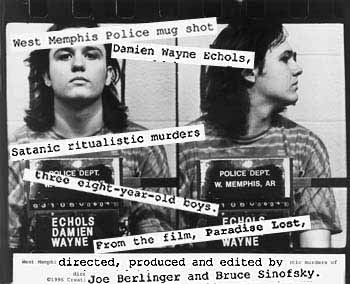

The Usual Suspect: A police mug shot of Damien Wayne Echols, one of three convenient accused killers in "Paradise Lost."

Prejudices swamp a southern town in true-crime documentary

By Richard von Busack

EVEN AT 2 1/2 hours, the deeply engrossing courtroom documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills doesn't deliver all the information we need to understand a tangled case. Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, directors of 1992's Brother's Keeper, were in understandable terror of making a boring film, and so they organized the material more for color than for facts.

The swampy town of West Memphis, Ark., is no one's idea of Paradise. Three 8-year-olds were found dead there in 1993--beaten, knifed, one of them castrated--behind a truck stop in an area the locals called "Robin Hood Hills." Three likely suspects were quickly arrested. West Memphis Chief Inspector Gary Gitchell proclaimed that on a guilt-scale of one to 10, the suspects were 11s.

Two of the defendants, Jesse Misskelley Jr. and Charles Jason Baldwin, were too good to be true--paradise to a DA. The prosecution needed them, in Preston Sturges' words, like an axe needs a turkey.

Misskelley, who confessed and later recanted, exhibits the classic room-temperature IQ of 72. The undersized Baldwin looks like he would have trouble subduing a rabbit, let alone a cub scout. The star suspect, Damien Wayne Echols, the smartest of the three, makes it worse for himself on the stand--like Milton's devil, he takes a fall for the sake of vanity.

A diffident young man given to playing with his hair while his life is on the line, Echols comes across as possibly an intelligent psycho. If he is, though, it's despite what was proved in a prejudicial trial that hinged on circumstantial evidence, particularly Echols' interest in Alistair Crowley and Wicca.

Echols' Goth tendencies wouldn't, as the saying goes, get him arrested in California; being a high-profile misfit in the priest-haunted South contributed greatly to his fate in court. That he and his chums liked heavy metal and black clothes only compounded their problems. One of the more infuriating moments is watching Dr. Dale W. Griffis, PhD, the state's occult expert, who is as meretricious as the inept jail-house squealer the prosecution unearthed to slander Misskelley. "West Memphis is a second Salem," says Echols, and whether he's a murderer or not, you can't contradict him.

Who killed the children? The film leaves the question unanswered. It's a case fit for Scully and Mulder. Sinofsky and Berlinger, as intrepid as the fictional FBI agents, made the look of the film as cold and blue as The X-Files. The two worked hard to open up the populace, particularly the grief-stricken and vengeance-crazed father John Mark Byers, who would have been a suspect in any court not staffed by marsupials.

Like so many other of the locals, Byers looks as weird to us as the Satan-metal kids look to the God-fearing. At times, Paradise Lost does what it accuses the prosecution of doing, of playing on prejudices. Any reservations about the filmmaker's approach, however, is dwarfed by the curiosity it teases. This fascinating, strange case begs for a sequel. I want to see how the appeals go.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (Unrated; 150 min.), a film by Bruce Sinofky and Joe Berlinger.

From the December 5-11, 1996 issue of Metro

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)