![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Noble Romans

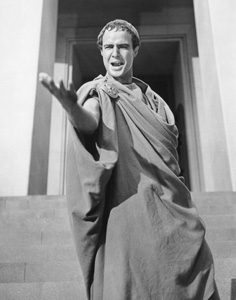

Marlon Brando showed the two faces of a politician as Marc Anthony in 1953 film of 'Julius Caesar'

By Richard von Busack

IF THE ONLY THING the 1953 movie of Julius Caesar had going for it were Marlon Brando's Marc Anthony, it would still be worth revisiting. The film was created in a politically disappointed Hollywood—shortly after the triumph of the drowsing Eisenhower over the smarter, more idealistic Adlai Stevenson—that is a distant mirror of today. Julius Caesar was considered a financial risk, and director Joseph Mankiewicz, as well as all the critics, fretted about the film's low budget. Yet the black-and-white photography adds grit; the recycled sets from the epic Quo Vadis?, shipped in from Italy, look lived in and are decorated with authentic graffiti. And there is a wedge of brown California hills, looking authentically Italianate, visible from the very steep staircase of the Senate. This Julius Caesar is an artistically conservative, stagebound production. Yet it swarms with hundreds of extras, and the teeming mob is always a presence and a problem.

The archcynic Mankiewicz (All About Eve) has a favorite character, Edmond O'Brien's grim Casca, the reportorial nobleman disgusted by the "foolery": the dog-and-pony show that Caesar and his disciple Anthony put on with the thrice-offered crown. But the other actors have their due: James Mason as the frightened, bad-nerved Brutus, who is the last to strike; and John Gielgud as the shallower, slicker Cassius, who turns him to assassination. Louis Calhern is very much the Chicago ward boss as Caesar; he is an easily flattered bruiser who has already begun to refer to himself in the third person, always an alarming sign in a politician.

Every high school student keelhauled through Julius Caesar can say by rote "It's a play about too much ambition." Instead, Shakespeare savages the idea of self-made royalty, lamenting the end of the Republic and the "serpent's egg" of absolutism hatching. Through Brando's magnificently manipulative, 20-minute-long funeral oration, it becomes clearer that this version isn't about the politics of Anthony, but the brutality of politics.

There's a part of the viewer that must mourn that the conspirators didn't ice Anthony when they had the chance. First, Anthony breaks a handshake deal with the senators, then he craftily works his own gambit to set the mob on fire. Brando has to make his "Friends! Romans! Countrymen!" heard in the midst of a major hubbub. The statuesque actor crouches on the high steps of the Senate—stooping further when it pleases him. In close-up, we see his calculation, gauging when to display the daggered corpse, figuring how long to tease the mob with the scroll containing Caesar's will. In his clouded brow and half-smirk of triumph, we see a master politician at work. "As the people warm to him, he is thinking, "suckers," wrote critic Anthony Lane. Maybe so, but we're grudgingly on Brando's side because we've seen the look he's concealing from the crowd: "Are they buying it?"

The subject here is of the peculiar ugliness of public life and the twofold choice available: those who overcome their disgust and get their hands bloody like Mason's Brutus. And those, like Brando's Anthony, who are shrewd enough to get their dirty work done for them.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

Toga Party: Marlon Brando delivers the funeral oration in 'Julius Caesar.'

Julius Caesar (1953) plays Dec. 10 at 7:30pm and Dec. 11-12 at 3:20 and 7:30pm, with Desiree at 5:30 and 9:40pm at the Stanford Theatre in Palo Alto.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com.

From the December 8-14, 2004 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.