Elephant at Prayer

Telling moments salvage ponderous 'Amistad'

THE SLAVE REVOLT aboard the ship La Amistad was a small harbinger of the Civil War. After the vessel was hauled into the harbor at New Haven, Conn., the slaves were tried for mutiny; eventually the case went to the Supreme Court. The 1839 trial of the mutineers provides director Steven Spielberg with a window into the African diaspora, and this may be where Amistad went wrong: the subject is so huge and the window is so small.

Although the film goes aground, there are some telling moments in the details. Crashing a dinner party and defending slavery, Senator John C. Calhoun (Arliss Howard) explains the theory that led historian Richard Hofstader to call the Southern senator "the Marx of the Master Class." (Conservatives ever since have used variations of argument: slaves always hold up an elite, no matter where the elite was or what the slaves were called.)

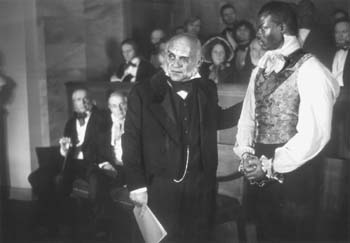

In the courtroom scenes, Anthony Hopkins--as John Quincy Adams--displays complete ease with the florid, complex syntax of an older age. In real life, Adams was prouder than Lucifer, but he is portrayed by Hopkins as a dear old codger. This is your chance to see Hopkins play the reformed Ebenezer Scrooge.

His opponent in the Amistad case is Nigel Hawthorne, simpering pleasantly as President Martin Van Buren. The Little Fox, they called Van Buren, but, as usual, Hawthorne is more like a coyote. But Van Buren uses proxies in court, and the rivalry between the two presidents isn't brought to a head. And Amistad is aligned with Calhoun's theory more than I suspect Spielberg might like; it's is another example of the "great men" school of history.

The mutiny's ringleader, Cinque, is played by the grave, handsome Djimon Hounsou. Even though he's inexperienced, he has enough presence to share the screen with Hopkins. In one scene, Cinque, furious at the law's delay, burns his clothes and screams in rage in silhouette in front of a fire. Hounsou's charisma makes Spielberg's dubious foreshadowing of black nationalism work.

Cinque, however, is still condescended to in subtle ways. Essentially, the African hero is an E.T. who wants to go home. Matthew McConaughey, as Cinque's lawyer Roger Baldwin, draws a map in the dirt to show Cinque how far away Africa is.

IN AMISTAD ARE ALL of Spielberg's faults, and all of them are writ large. The Africans who actually pulled off the revolt are almost extras; they're more indistinguishable, rather than less, as the movie goes on. The women characters are all but nonexistent; it's a shock in those rare moments when a woman actually shows up on screen. And once again, Spielberg also manages to squeeze in his lost-father shtick. The director suggests, heavily, that John Quincy Adams has some issues with his own dad, John Adams.

The slave-ship passage is a realistic, horrible, bloody spectacle, with lashings and drownings and starvings. These scenes are violent but not piercing. You can't get anything out of the scenes to make you transcend your disgust, especially since these moments are in the same film with an upbeat Grishamesque courtroom triumph.

Spielberg layers dignity on slavery, this tremendous historical indignity. No doubt Amistad's piety is a salute to the role of the church in African American life, but the discovery of an illustrated Bible by two of the Africans is the low-water mark of the film--they trace out the story of the crucifixion like one schoolboy to another.

When a movie of this size gets on its knees, it's like watching an elephant at its prayers. John Williams' score has never been so churchly, with choirs and French horns. Nearly three hours of this and you think that the last line of the film should be "The mass is over, thanks be to God."

For all of the movie's scope and expense, the best scene consists of one great actor in one intimate moment. Morgan Freeman plays Joadson, a freed slave and journalist inspecting a slave ship. Overcome with curiosity and horror, he loses his balance and is entangled in the hanging iron chains in the hold, like a fly in a web. It's a strong image suggesting the problem of examining history only to find yourself emotionally overwhelmed.

And it's subtle too--unlike the slave-ship scenes, in which Spielberg overwhelms us. The director is trying to teach a lesson about slavery, which he presumes we've forgotten. Maybe the film was therapeutic for him; maybe kids and the ignorant can profit from it. But if you're the kind of person who couldn't put the horrors of slavery out of your mind on a bet, you'll wonder why you're being dragged through it. And you'll wonder how Spielberg could dare imply that you'd ever forget.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Advice of Attorney: John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins) takes up the cause of rebel Cinque (Djimon Hounsou) in the courtroom scenes of Steven Spielberg's 'Amistad.'

Amistad (R; 152 min.), directed by Steven Spielberg, written by David Franzoni, photographed by Janusz Kaminski and starring Morgan Freeman and Djimon Hounsou Hopkins.

From the Dec. 11-17, 1997 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)