![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

Buy 'The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay' at Amazon.com |

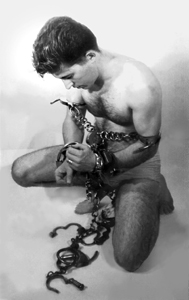

No Chains, No Gain: Before he revolutionized comic-book art, Jim Steranko plied his trade as a modern Houdini. Escape Artist Comic-book artist Jim Steranko helped the genre escape its bounds--and ended up in the pages of Michael Chabon's novel BEING BURIED alive, dropped from Ferris wheels and chained to railroad tracks are things Jim Steranko knows firsthand. Anyone who has been trapped by life understands the appeal of hairsbreadth escapes--the source for stories as different as the 007 films and Robert Bresson's A Man Escaped. Such stories are enough, also, to link two celebrated writers. At Lee's Comics on Dec. 14, the legendary cartoonist and escape artist Steranko and his admirer Michael Chabon, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, will meet for the first time. Steranko's new collected works, Steranko: Arte Noir, will make its debut at the event, with free lithographs for the first 500 attendees. Lee Hester of Lee's Comics says, "It's my favorite all-time writer meeting my all-time favorite comic-book artist." The Berkeley-based Chabon wrote an appreciation of Steranko for his website, using some of Steranko's illustrations for a series of deathtrap escapes. And he based his novel's title hero, Joe Kavalier, in part on Steranko. Fan response to Steranko can be summed up by cartoonist Mario Hernandez, one of the Love and Rockets Hernandez brothers. "Steranko--the 'Jim' is superfluous to true comics nerds--evolved the straightforward illustrative style of comics to the groovy graphics/psychedelic form of storytelling that's so prevalent now, in a short time. He's one helluva draftsman." Not every one is enamored of Steranko's art. Gary Groth, publisher at Fantagraphics Comics, allows only that Steranko's "big contribution was the bringing comics up to the technical level of a James Bond movie." True, other artists at that hallucination-works known as Marvel Comics pioneered what Steranko did. Jack Kirby created double-sized "splash pages" depicting colossal machinery vs. masked heroes. The cover of the first Kavalier and Clay comic book, as imagined by Chabon, is a ringer for the design of Captain America No. 1 in 1941, created by Kirby and Joe Simon. And in the 1950s, Will Eisner integrated images and words into frame-breaking combinations. In his Marvel days, though, Steranko transplanted to comics the kind of montage that was revolutionizing 1960s movies. Steranko had a short but influential run in 1967 with the James Bondish Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. (Supreme Headquarters International Espionage Law-Enforcement Division). In these now-classic pages, Steranko worked large--capping one episode with a fight between a live Tyrannosaurus Rex and a robot King Kong. But he also worked on an intimate scale. Consider a tender sex scene, forbidden by the Comic Code but implied by Steranko: In mute boxes, we see a stereo turntable, lips, a telephone that might ring at any second, a woman's face bisected by a rose stem; lastly we see Fury's gun, resting in his holster. You don't have to be Freud ... In Chabon's description of Joe Kavalier's art skills, he sums up what Steranko knows best: "His [Kavalier's] experience with film vocabulary, his sense of the emotional moment of a panel and of the infinitely expandable interstice of time that lays between the panels of a comic-book page." Steranko, retired from the escape-artist's trade, makes a living as an illustrator and conceptual artist. He helped design Indiana Jones and came up with imagery and textual ideas as project comceptualist for Francis Coppola's version of Dracula. He's also working on the next Coppola movie, which he's contractually forbidden to discuss. Steranko is the inspiration for Joe Kavalier--and the unpaid source for Kirby's Mister Miracle comics. But maybe he's really a model for Buckaroo Banzai as well: a pop-culture Renaissance man, not just magician and artist but a filmmaker who collaborated with Alain Resnais, the author of a history of comics and a hardworking journalist. "I've probably done more writing than anything else," he says. Steranko was also a professional rock musician who gigged with Bill Haley. Steranko says, "I was always more comfortable playing music than any other endeavor I've attempted." In his younger days, Steranko used to be buried alive to divert the crowd at baseball games. Regarding premature burial, he has explained, "There are a number of disagreeable sensations to fight: first, weight; second, heat; third, silence; and finally, pressure so great that it's impossible to even flex a muscle. ... The real problem of doing an underwater-box escape is to have the box sink steadily and quickly to the bottom. Boxes that rolled or spiraled in the water were deathtraps." In some respects, the art of comics and the art of magic are aligned. Steranko says today, "With some escapes, for example, such as underwater stunts, death is an imminent factor, bringing the metaphysics of eternity with it, especially if one has a philosophy of afterlife or reincarnation. Since comics frequently deal with their reality, not ours, metaphysics is part of the architecture. I've experimented many times with the concept of transcending that reality to explore ideas at a higher or more sophisticated level." In writing about a cartoonist who was also a magician, Chabon turned back to the history of America in the 1940s. Joe Kavalier escapes Nazi-occupied Prague in the company of unliving monster the Golem (grandfather of Superman and Frankenstein, but that's another story). The initial K in Kavalier may be a nod to Prague's most hopeless dreamer of escape and transformation, Franz Kafka. In America, Kavalier finds work in the nascent comic-book industry, creating, with his cousin Sam Clay, a sort of super-Houdini called the Escapist, but love and war undo the team. Chabon's marvelous novel concerns the way Jewish messiah lore took shape in these leotard-clad characters--how the old myths fit into the new ones like a lock into a key. "Clark Kent, only a Jew would pick a name like that for himself," jokes Chabon's Sammy Clay. Steranko himself notes, "I've always found it to be very ironic that the great American superhero was created by Jews: Siegel, Shuster, Kirby, Simon, Lee, Kane--both Bob and Gil--Eisner, Kubert. The list is very long." Steranko's escape proclivities helped comics escape from their sober boxes into vivid pages that changed the art forever. His appearance with Chabon should make for a rare meeting of the minds. Those still-disreputable comic books have been helped by these two talents, who have done their part to elevate the medium, to bring it new ideas and new respect.

Michael Chabon and Jim Steranko appear Saturday (Dec. 14), 2-4pm at Lee's Comics, 1020-F N. Rengstorff Ave., Mountain View. (650.965.1800)

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the December 12-18, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.