![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

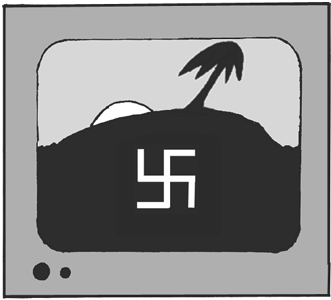

Techsploits Social Experiments By Annalee Newitz HAVING RECENTLY read Lauren Slater's interesting essay on the Milgram experiments back in the 1960s, I am now certain that reality television is unethical. Stanley Milgram, if you recall, was a Yale psychologist who wanted to study obedience. Deeply disturbed by what had happened in Germany during World War II, Milgram crafted a simple experiment to find out whether it was indeed true--as many Nazi collaborators claimed--that ordinary people could be made to commit unspeakably cruel acts under the influence of authority figures. Posing as an education researcher, Milgram told his subjects that he was studying "learning." He hired an actor who posed as the "student" in the experiment when the subject arrived at Milgram's lab. The actor was hooked up to wires that, Milgram explained, would deliver a shock whenever the hapless subject pulled a lever. In his role as experimenter and authority figure, Milgram told his subjects to deliver greater and greater shocks to the actor whenever the actor got answers wrong on a series of "learning tests." The actor would howl in pain and often pretend to have a heart attack before passing out. Sixty percent of the subjects, at the urging of their authority figure, continued to shock the actor after they reached what they believed were lethal doses of electricity. Needless to say, it was an experiment that freaked everybody out. Subjects who discovered they had been deceived were enraged. What they thought was a learning test was in fact an obedience test. Not only had they been misled in a somewhat creepy way, but now they had to live with the knowledge of how easily they had gone Nazi, as it were. After Milgram published the results of his studies, his work was harshly criticized by his fellow psychiatrists. Eventually, this outcry lead to the establishment of strict ethical guidelines in the psychiatric community regarding experimenting on humans. These days, if a researcher wants to experiment on a human subject, she must first petition a review committee and explain exactly what she'll be doing. Then she must gain explicit consent from all human subjects involved in the experiment. No deception is allowed. Today, you just can't do a Milgram-style experiment. And yet, as Slater points out, there is a kind of loss we suffer as a result. It might be helpful to know that when it comes down to brass tacks, 60 percent of your neighbors would probably help the Homeland Security forces throw you and all the other so-called "terrorists" into that scary "alternative justice system" Bush is so excited about. And yet ethicists have legitimate reasons to limit the covert experiments of scientists. Unlimited, nonconsensual testing of humans led to the horrifying Tuskegee experiments, for instance, whose unwitting subjects were left with untreated syphilis rather than just an identity crisis. And this is where reality television comes in. The entertainment industry has no qualms about using human subjects in its experiments. These days, Milgram could just watch the Survivor or Big Brother if he wanted to discover the depths to which people will sink in their quest for approval from authorities. Of course, the authority figures motivating antisocial behavior in these shows are more nebulous than a man in a white lab coat (or SS uniform). Contestants on Survivor fight for cash, for audience approval and for alliances with teammates. In a consumer-entertainment economy such as our own, these represent some of our most potent authority figures. Big Brother, conspicuously named after the friendly face of fascism in George Orwell's classic novel 1984, urges its human subjects into the weirdest forms of servile behavior imaginable. On a recent episode of the British version of the show, subjects were forced by the disembodied voice of Big Brother to engage in quilting for a 24-hour period. If they didn't, they were told they would suffer "consequences." Similarly bizarre scenarios await subjects on MTV's long-running Real World, where Big Brotherstyle surveillance is often coupled with some kind of Survivor-ish group task, like starting a business together. Having never particularly cared before whether reality-television contestants were being treated ethically, it was with some surprise that I discovered that not a single one of these shows would pass muster with a committee for the use of human experimental subjects. If a researcher told such a committee, "I'm going to do an experiment where I put people on a deserted island without food or water and force them to perform surprise tasks for a series of weeks," the committee would vote them off the island of academia. And yet we the public want to know the results of that forbidden experiment so badly that we've handed off the responsibility of ethical oversight to Hollywood execs. Obviously, despite our best intentions and all our regulations, the Milgram experiments go on. I suppose the question now is if these experiments will teach us anything about ourselves.

Annalee Newitz (realitycheck@techsploitation.com) is a surly media nerd who likes to experiment on human subjects.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the December 12-18, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.