![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

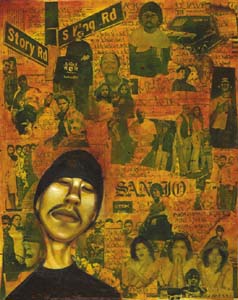

Photograph by Samuel Rodriguez Color on the Lines: Chicano communities are being thrown in each other's faces--and the results of the conflicts are written on the walls. Street Dreams Are Made of These Red vs. Blue. Norteño vs. Sureño. And the San José-ing of Central Valley. A writer looks at the changing nature of Chicano identity. By David Madrid SILICON VALLEY De-Bug is a grassroots collective made up of young artists, writers, educators and activists. A shared sense of disenfranchisement spawned the group in 2001--a sense that in the midst of the mainstream media's obsession with all things dotcom, stories of actual people were being left behind. Founder Raj Jayadev says that the group determined that "if the mainstream media [would] not allow us our space in the public imagination, shouldn't we carve out our own?" Two years later, a core staff of 10 part-timers operates out of the San Jose Peace Center. The nonprofit group puts out a bilingual zine every three months, runs writing and arts workshops, maintains two websites and produces a TV and a radio show. "Our goal," Jayadev says, "is to be a platform for civic voice, engagement and leadership for the South Bay's young adults." Two principles guide this goal, he says: "To ask questions to which we do not know the answers" and "to give the ultimate authority to personal experience." This last principle allows people with no great familiarity with writing to tell their stories. David Madrid started out as one of these people and has since become a staff member with De-Bug. The story reproduced here is from the De-Bug zine. More information about Silicon Valley De-Bug can be found at www.siliconvalleydebug.com.

Driving through the back streets of East Side San Jose, you can feel the piercing stares. Everyone wants to know who is driving down their block. There is rising tension in these neighborhoods as the population grows, and you can feel it on the streets and in the schools. Different identities among our Chicano communities are being thrown in each other's faces--mashing them together--and the results of the conflicts are written on the walls. As Chicanos move all around the state to find jobs and get cheaper housing, regional differences are becoming more obvious, and they are escalating the Norteño and Sureño conflicts on the streets, especially among the youngsters. Working at two different East Side junior high schools in San Jose, I'm hearing more stories of gang conflicts and violence--beatings, kids getting chased, knives or guns getting pulled. Kids show me their scars and wounds as they tell me their stories. The division of the north and south was born out of the gang culture that started in the California prison system and spread throughout the streets of Aztlan (pre-Aztec indigenous nomads roamed a mystical land called "Aztlan," which comprises present-day California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Utah and half of Colorado; this Aztlan is a romantic term Chicanos now use to describe our land) and nationwide. This north and south hatred is an idea that has torn the state in half. Most people think California's Latino gang conflict is about red and blue, but when it comes down to it, it's about geography. Red is north; blue is south--prison-issued colors from the pen. The colors are only flags, though, like wearing a jersey, signifying which side of California you identify with. As an 11-year-old kid living off of LaVonn and Sunset in east San Jose, I can remember needing a pair of shoes. I wanted them to be red. The northern identity had already been burned into my subconscious. Red was the color of choice, worn by my older brother and the big homies in the neighborhood. Without even knowing it, I was becoming a part of the identity. Growing up, I heard constant propaganda against the south from someone's uncle, dad or older brothers. It was always about conflicts they had in the pen or the streets, and how we were different, how they were below us and how when we saw them, it's on. The belief that one group is better than another--and the focusing on differences between groups--has been passed down through generations in a manner no different from that of the Klan or other American hate groups. Some Chicano children are taught at an early age by their parents; others learn from life on the street. In California barrios from the north to the south, where the gangster is king, to be a Norteño or Sureño is more than a style, it is a way of life for some. Although gangsters are only a small part of Chicano culture, the north-vs.-south belief system affects all Chicanos. You get labeled, whether or not you are affiliated. In this way, the ideology of northern or southern supremacy has become a common form of discrimination among Chicanos. In high school, I remember girls not liking a guy after hearing he was from the south. They didn't want to be known for dating a "Scrap." A friend told me that after having taken out his mother to eat for Mother's Day in an East Side restaurant, a carload of Sureños wanted to fight him. Apparently, my friend was wearing a Disneyland shirt that happened to be red. The north and south conflict is not just about senseless violence, though. It is about something deeper in our culture--our search for identity as Mexican-Americans, not from Mexico and not truly accepted as American. Whether it be claiming allegiance to a gang or a club, identity as Latino or Hispanic, Raiders or 49ers, being Chicano is about finding your niche identity and belonging to it. Despite media depictions to the contrary, this search does not always result in conflicts. It has also created different Chicano identities based on where we live. As people move around the state, we are seeing how different we are culturally, based on where we're from. In Northern Cali alone, for example, we have the East Bay, South Bay and the Central Valley Chicano. Although the 'hood is the 'hood, barrio life is different wherever you are. But it's not just the gangs--it's the clubs, clothes and even the cars that are different. A lot of East Bay Chicanos, and those from parts of San Francisco, have a hip-hop vibe, using what's traditionally thought of as black slang, calling each other "blood" or "nigga." It's common to see a young Chicano sagging his pants with his hat flipped to the side, just like out of Source magazine. Along with having typical Chicano lowriders, out in the East Bay they drive souped-up old-school muscle cars. It is this combination of black and brown that has created East Bay Chicano culture. In San Jose, we have that black/brown element, too, but it's not as strong as it is in the East Bay. The San Jose culture has a more traditional Chicano identity born out of the lowrider movement, the house and freestyle music club scene and Spanglish slang. Some homeboys out here are still sporting baby cuffs and butterfly-creased khakis, and though they listen to rap you'll still hear oldies bumpin' out of their Regals. A lot of South Bay folks are moving to cities like Modesto, Tracy and Fresno, and the Central Valley Chicano identity is changing as a result. What used to be a small-town vibe is starting to feel a lot like a young San Jose. Now it's common to see San Jo tats on arms. They even sell San Jose hats in some liquor stores in Modesto. Integration of the Bay Area immigrants, though, has not been easy. Back in the '80s, the Fresno Bulldog Norteños wanted to break off and form their own Central Valley identity. They didn't want to be part of the north or the south. To this day, there is still conflict between some Bay Area Chicanos and Fresno. While the conflicts with the Chicano community may be our main downfall, the differences are what make us unique as a people. Whether from the north or the south, or from the Central Valley, our struggle will always be about identity.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the December 18-24, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.