![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Jail Baited

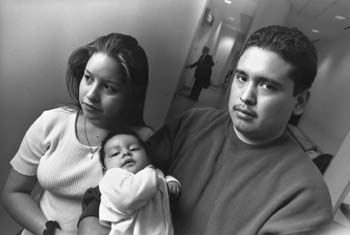

Robert Scheer Family Values: Even though they are married, 17-year-old Delia Lopez and 22-year-old Juan Jiminez and their baby son found themselves in court after a doctor reported them to authorities. A state-funded crackdown on teen sex is quadrupling statutory rape cases in Santa Clara County, sending hundreds of young fathers to trial. Researchers say that in this latest crime du jour, the Wilson administration skewed the data to support a political agenda. By Jim Rendon

SEATED IN THE BACK row of a courtroom in the basement of the Santa Clara County courthouse, a young couple talks quietly while waiting for the judge to arrive. A blue baby stroller packed with blankets rests next to them. As they talk, they take turns holding a tiny child, discernible only by his shock of thick, dark hair. These young people are in court because their very existence as a couple violates the law. Juan Jose Jiminez is 22. His wife, Luz Delia Lopez, is 17. Jiminez was arrested for having consensual sex with Lopez before they were married. The crime was statutory rape, sex with a minor. If he is convicted of the felony charge, he could spend six months or more in the county jail and get slapped with years of probation. The county has pursued the case against Jiminez even though his wife never filed a complaint. There was no violence in the relationship. At the time of the arrest, the two were living together with Lopez's parents, who consented to the relationship. Over the objections of everyone involved, Jiminez was arrested and spent 23 days in jail. After a number of court appearances, he has decided to plead guilty to a misdemeanor rather than risk the possibility of a felony conviction. "If he fought it, he could get a dismissal, but he would be playing with fire," says Molly O'Neal, the deputy public defender representing Jiminez. Though Jiminez and Lopez are doing nothing more than pursuing a relationship, starting a family and trying their best to get by, they have found themselves at the center of a hot issue in California and in Santa Clara County, where state-funded bus placards and radio announcements threaten menacingly: Have sex with a teen; go to jail. Though California's statutory rape laws languished on the books for decades, they are the linchpin of a new three-year, $76-million effort by Gov. Pete Wilson's justice department. The Wilson administration claims this will curb teen pregnancy, reduce billions in state and federal welfare payments to teen mothers and lock up "predatory" older fathers who impregnate teenage girls and abandon them, even though statistics show that this occurs in less than 8 percent of all cases. Critics say the plan is nothing but a political ploy to condition young people to say no to sex rather than use birth-control clinics, pointing out that grown men who impregnate teens create only a small percentage of the state's 63,000 teen pregnancy cases. In response, the state is spending $56 million over three years on community programs that address teen and unwed pregnancy, $11.6 million on mentoring programs for young men, and $8.4 million a year on the prosecution of cases like Jiminez's. In a 1995 pilot project, 14 counties received grant money to dedicate a team--attorney, investigator and paralegal--to handle statutory rape cases. Two years later, 52 of California's 58 counties are receiving the special funding. Santa Clara was one of the first counties to get the grant and has kept going back to the till to fund what is the state's most aggressive prosecution program. This year the county received $275,000 to prosecute the crime, and it will receive another installment next year. Though this sum is a drop in the bucket for a DA's office that spends $34.7 million a year on criminal prosecutions, it can now put two full-time attorneys, one full-time and one half-time investigator and a paralegal on the statutory rape beat. Rather than a traditional setup whereby one attorney handles specific parts of each case, the grant allows a prosecutor and an investigator to follow each case from start to finish, which results in higher conviction rates. Jo Anne McCracken, the deputy district attorney who heads Santa Clara County's program, says that prior to getting the grant, her office prosecuted 35 statutory rape cases a year. Since receiving additional funding in February 1996, the county has handled 280 cases. This leap in prosecutions here and in counties around the state is due mostly to the strong push from the governor's office to dust off the law books and get offenders behind bars. That initiative, which reached its highest level of funding this year, was sold to the legislature with the help of one very disturbing statistic. Anyone involved in the governor's push to end teen pregnancy is quick to throw that number out up front. It is meant to grab and shock and garner support for Wilson's punitive approach: two-thirds of all teen pregnancies are caused by men over 20. This is a troubling statistic for anyone worried about what their daughter is doing after dark, or for deficit hawks who see teen pregnancy as the gateway to multibillion-dollar welfare expenses. But that number reveals little about statutory rape and has been misused by those trying to push everything from abstinence to putting more people behind bars, says Susan Tew, a spokeswoman for the Alan Guttmacher Institute, the organization that first published that statistic. Minor Differences THE FIGURE FIRST appeared in "Family Planning Perspectives," published by the Guttmacher Institute. When researchers conducted the study, they were interested in teen pregnancy itself, not who was having sex with minors. Using a national database, the group studied teenagers through age 19 who gave birth. They found that most teen pregnancies were the result of sex with a man over age 20. But the majority of teens who gave birth were between 18 and 19 years old. And the study did not look at age differences between the men and girls, usually a requirement for prosecution. Because of the broad focus, this study revealed nothing about statutory rape. Despite the study's focus on overall teen pregnancy, the buzz about statutory rape was soon out of control, Tew says. Once the fudged statistic appeared in a New York Times article, the term "predator" was on everyone's lips. "This is a study in what happens when people look for data to substantiate a problem that they think exists. It is frustrating to see what happens and to try to reel it back in," she says. In an effort to curb the misuse of its findings, the institute published another study in March of this year. This time researchers used the same data as the first study but weeded out the 18- and 19-year-olds. Since many states require a minimum age difference between the partners for prosecution (Santa Clara County only prosecutes if there is more than a three-year age difference; Florida only prosecutes if there is more than a seven-year age difference), the group looked for unmarried couples where the men were five or more years older than the girls. The results were dramatically different than the first study's. The researchers found that statutory rape by this definition was responsible for only 8 percent of teenage births. And with similar criteria applied to 13- and 14-year-olds, researchers found that they accounted for less than 3 percent of all teen births. "This can be seen as an area for serious concern," says Leighton Ku, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute who co-authored the study, "but not anything that is a major responsibility for teen pregnancy." Nonetheless, California was off and running, aggressively prosecuting hundreds of cases a year as a means of attacking the teen pregnancy problem. In conjunction with locking people up, the state and some counties also have produced ads to warn men away from teenage girls. Earlier this year, McCracken's office bought space on the side of buses for placards that read, "Sex with a teen will land you in jail. We prosecute statutory rape." The state has bought both radio and television time and is running ads in both English and Spanish. One TV ad reads: "A truth about sex." A young man speaks: "The judge does not care who I am. The jury does not care who I am. They only know I got myself involved with a 16-year-old girl. And now I am a rapist. A statutory rapist.' I had never heard those words!" The announcer fades in: "Listen to this: Having sexual relations with a minor under the age of 18 is called statutory rape. And you will go to jail. This is a truth about sex." Chastity Bars THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN teen pregnancy and statutory rape, and the improbability of affecting one by prosecuting the other, seems to be lost on those who support the governor's program. Lisa Kalustian, spokeswoman for Gov. Wilson, is unfazed by the distinction or the radically different findings of the most recent study published by the Guttmacher Institute. "Laws on the books need to be enforced," she says. "Beefing up enforcement has a strong deterrent effect. We are sending a strong message that this behavior will not be tolerated." That robotic "lock 'em up" message from Sacramento is trickling down to nearly every county in the state through the special grants for prosecuting this flavor-of-the-month crime. McCracken, who has made a career of taking on more traditionally prosecuted sex crimes like rape and child molestation, says that her program provides support for teen girls in manipulative relationships who need someone to stand up for them. "The vast majority of cases are not young couples in love where he supports the child," she cautions. "In most of the cases, he has kicked her in the stomach, there is domestic violence, he is not supporting the child or he is supplying the girl with drugs." Like those at the state level, McCracken paints a frightening picture of a predatory older man who takes advantage of teenage girls with low self-esteem, knocking them up, beating them up and leaving them for the social service agency to deal with. She says the average age of those who stand trial for statutory rape in the county is between 20 and 24, and the majority of girls are 14 or 15 years old. But from statistics provided by the Santa Clara County Public Health Department, it appears that statutory rape is hardly rampant among teens who give birth in this county. Of a total of nearly 26,000 births in 1995, only 2,200 involved teenage mothers. Of those, 1,300 were 18- and 19-year-olds. That leaves 944 teen births in which the mother was under 18. For the majority of those births, the county had information about the age of the father. It turns out that statutory rape, among teenagers giving birth in Santa Clara County, is a small problem. Only 18 percent of teen births were the result of sex by a couple in which the man was more than three years older than the girl. This includes couples who, like Jiminez and Lopez, were married at the time their child was born. As for McCracken's main problem group, men between 20 and 24 and girls between 14 and 15, only 47 births in the county in 1995 were from couples who fit this description--2 percent of all teen births. Such numbers which might be better handled by regular prosecution channels at the district attorney's office, instead of by a state-funded push to put more people in jail. Of those McCracken's team does put behind bars, more than 20 percent are under age 20, and one-third of the girls on whose behalf McCracken prosecutes are age 16 or 17. When asked about the second study published by the Guttmacher Institute, McCracken says that she finds it hard to believe, that those less inflammatory numbers do not mesh with her own experience. But, she admits, the cases she sees are often those in which there are problems, because of either an abusive boyfriend or a disapproving parent. Jana Cunningham, with Planned Parenthood in San Jose, who sees a broader cross-section of sexually active teenage girls, says that the small percentage of statutory rape found by the second Guttmacher Institute study seems far more realistic than the numbers the state parades. And age difference alone, she points out, does not necessarily create an abusive, manipulative relationship. Jiminez, who is five years older than his wife, is doing his best to make things work. Looking into his eyes, it is hard to see him as a predator. He is quiet, polite and a whiz at quieting down two-month-old Juan Angel. O'Neal, his attorney, who handles felonies when they are first assigned to the public defender's office, says that cases like Jiminez's are common. "I get one case a week which I don't know why is in court. The couple is happily together. He is working and supporting the child, they intend to be married and live with the girl's parents. "What purpose does this serve?" she asks. "It just clogs up the courts with cases where no one is punished." Indeed, when Jiminez offers a plea of no contest, there is no punishment. He is sentenced to time already served and sent on his way. Even the fees to a victim restitution fund and to the county are waived. "Spend the money on your child," says Judge James Emerson before moving on to the next case. Despite the time, money and energy put into prosecuting these cases, there is no evidence that arresting these men, putting them before a judge and hanging the specter of real jail and even prison time in front of them will have any effect on teen pregnancy. California is one of the first states to try this approach, and no one in Sacramento could point to any state or country that had successfully curbed teen pregnancy via prosecution. "There is no analysis that says enforcement of statutory-rape law as a means of lowering teen pregnancy rates will have any effect," Tew says. Gabriella Castellon, a spokeswoman for Planned Parenthood in Sacramento, believes that enforcement is wrong-headed. "We should spend more money on education and less on prisons," she says. "We need to educate young people so they don't pursue unfit relationships, rather than waiting until they commit a crime." For Castellon and others in the family-planning business, education is the key. Sixty percent of all women, regardless of age group, become pregnant unintentionally. Castellon says what is needed is more programs like the ones Planned Parenthood already runs that work with young men in high school and the California Youth Authority. "These are programs in which peers educate peers about the importance of male responsibility. We talk to young men about the importance of not having sex with underage girls and about protecting themselves and others from sexually transmitted diseases and not impregnating someone. These are programs with a positive focus," she says. Other Planned Parenthood programs provide support for teenage girls with and without babies. Though Planned Parenthood is hoping to receive additional funding from the governor's program to address teen pregnancy, the organization has yet to see grants come its way. Arresting Numbers DESPITE THE DEARTH of funding and the controversy that always surrounds sex education programs, especially those that provide information about abortion, there is evidence that the educational approach taken by some schools, governments and community groups is already working. "I am optimistic; things are getting better," researcher Ku says. His optimism is well-founded in the numbers, which have been looking up for some time. Years before California began throwing people in jail for having sex with minors, teenage pregnancy rates were falling. The rate nationally and in California has dropped steadily since 1991. And though California's overall rate is still above the national average, it's falling faster than rates in the rest of the country. Even Santa Clara County's pregnancy rate is below the state average. According to the state Department of Health Services, last year Santa Clara County teens age 15 through 19 gave birth to 2,137 children, down from 2,204 in 1995. Despite the drop in pregnancy rates, the number of reported cases of statutory rape in the county has increased many times over. McCracken says that before receiving the grant money, her office never turned any cases away but only saw about 35 a year. Since receiving the grant, the county has been involved in outreach programs: participating in workshops with schools and police, giving lectures to young men and running public service ads. With more awareness at every level, she says, "cases started to pour in. A lot of people had no idea that they could do anything about it." According to McCracken, cases arrive on her desk through many avenues, including parents who are concerned about their daughter's relationship, police checking domestic violence calls and even doctors who report on their patients. When Jiminez's case found its way to the district attorney's office, both he and Lopez felt betrayed. Lopez's doctor at Kaiser Permanente's Santa Teresa hospital turned her in after a visit when she was two months pregnant. Within a week the couple received a call from the police department. Though the officers assured them that charges would not be pressed, a few months later Jiminez was picked up and charged with statutory rape. McCracken says that health-care providers are required by law to report any instance where a minor has been sexually active with a significantly older man. "We have a legal responsibility to report, but we don't report without a thorough investigation," says Kaiser spokeswoman Kathleen Roberts. Right now, there is some leeway in reporting, but starting in January, the doctor's discretion will be further curtailed. Next year, if a physician sees a case where there is a sexual relationship between a man over 21 and a girl under 16, he or she will be required to report the case. Chances are that more cases like Jiminez's will land in court with the implementation of this new law. With more physician reporting, additional cases where there was no call for intervention because of violence or parental concern will find their way to McCracken's desk. And more young couples will find themselves before a judge trying to explain why they are involved with each other. After pleading guilty to a misdemeanor charge of sex with a minor, Jiminez walks the length of the courtroom back to where his family waits. He and Lopez gather up their son and push the baby carriage out into the hallway. The experience, says Lopez, has been frustrating and scary. "Loving somebody," she says, "is not a crime." [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()