![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

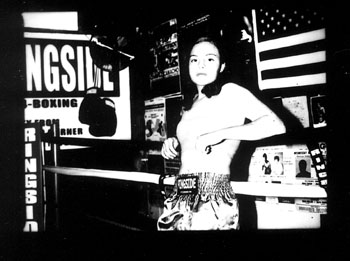

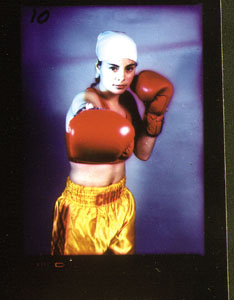

Photographs by Christopher Revell Tough Fight: Chris Martiñon and other female boxing advocates hope that women's boxing will make it into the Olympics by 2004 or 2008, but the International Olympic Committee remains undecided, citing a reluctance to add women's events while cutting men's. Let Us In! After years of fighting, will women's boxing finally cross the Olympic barrier? One young San Jose champ is ready. By Allie Gottlieb THE STARTLING clang of a boxing-round bell, followed by involuntary grunts of exertion and the slaps of a glove hitting a punching bag, fills a homemade private gym in an east San Jose backyard. Chris Martiñon, 16, dances around a corner of the red ring, throwing jabs and hooks into the air. Hands wrapped with tape, eyes focused straight ahead, she blows out quick, powerful breaths as she waits for her turn with the coach. "Her work ethic--that's what cuts her above the rest," says heavyweight boxer Bernard Gray, who trains in the same gym and beats on a punching bag while Martiñon spars. "You don't ever see her drop her hands." Martiñon earned a black belt in tae kwan do at the age of 11 but switched to boxing five years ago, she says, because "it was rougher, I guess." She began winning trophies and titles after just a year in the ring, nabbing the Women's National Golden Gloves Championship title for her age group and weight class (she's now 119 pounds) in 2001 and 2002. If junior amateur boxers (that is, fighters under 17 who compete in tournaments for glory not money) were ranked, she'd probably be tops in the country. A video of the three matches at this year's Golden Gloves Championship in Chicago shows Martiñon's merciless combinations disorienting two of her three opponents, causing the referee to give them standing eight counts to test their consciousness--and ultimately ending the third match early and winning Martiñon the championship title. "She's the best in the nation," says her mom. Her room is painted powder blue. On her twin bed lies a pink stuffed bunny, which her dad, Hector, gave her when she was born. The teddy bear from last year's secret Santa gift exchange at school sits affixed to the corner near the ceiling. She adores Eeyore from Winnie the Pooh and has stuffed donkeys and dolls all over the room. She even rescued a favorite Eeyore patch from a sweat shirt she outgrew and attached it to her book bag. She made a wooden tribute to the Chicago Bulls (from when Michael Jordan was on the team), which hangs on wall. When she looks in her mirror, her reflection appears beside a magazine photo of boxing champ Oscar de la Hoya. Above the mirror are two first-place boxing awards and one second-place tae kwan do award, which she received after being disqualified from first place for hitting her opponent's chin. "Even when I was fought guys," she recalls, "they would cry." In the ring, Martiñon's style is assertive. She leads, usually chasing her opponent rather than backing up. Even after taking hard punches to the head, she bounces back, alert and quick. On the Saturday of our interview, she is scheduled to fight a girl in Sacramento, someone she beat in Reno several months earlier. At the last minute, her opponent cancels the match. "She was scared," says Martiñon's mom matter-of-factly. "And her coach didn't want her to fight Chris." Martiñon displays a humility and confidence beyond her years. She generally sits on the ropes after a fight to let her opponent climb out of the ring first. To make money, she works cleaning her parents' catering-business truck once a week for $20 or $30. Her sweetness is balanced by a modest confidence. Martiñon, who has 39 wins and one loss under her belt, and has never been knocked out, is shooting for the Olympics. "Amateur boxing is a sport to make you go somewhere," she says, explaining that boxers don't get paid and don't box just to "lose their bellies" or to beat people up. The amateur boxing coaches, she says, "prepare you to go to the Olympics. They have big goals." That she has this ultimate aim, a bright light at the end of a sweaty and sometimes bloody tunnel, is significant because, as it stands right now, there is no women's boxing in the Olympics, and there may never be.

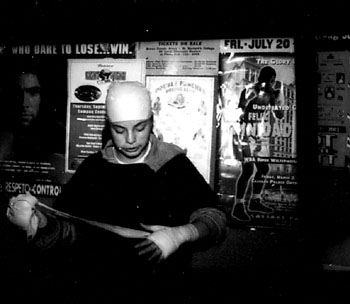

Sleepless in San Jose It's 4:45am, and Martiñon is up and running, something she does for 45 minutes almost every day before school. She is a junior at Yerba Buena High School with nearly straight A's in a full slate of honors classes, and her homework sometimes keeps her up until midnight or 1am. And Martiñon loves math. "It's so self-explanatory. It's not like English--symbolism, uggh ..." she says. She plans to study engineering at Santa Clara University after she graduates. After school, she trains in the gym in her family's garage for two hours. "Oh, no wonder you're so buff," her friends say when she tells them she's a boxer. "Move, move, move," her father, Hector, coaches. "Harder, harder," he says in Spanish as he fields her punches and directs her. her mother, Jenny, is from El Salvador, and Hector is from Mexico. Hector speaks less English than Jenny; Martiñon has both languages down cold. Telemundo recently interviewed her in Spanish. Hector is a trainer and former boxer. His daughter, who doesn't remember ever seeing him fight before he retired 10 years ago, is the only girl he trains. He coaches her at their backyard gym, the Silicon Valley Boxing Club, which is licensed with the country's official amateur-boxing organization, the U.S. Amateur Boxing Association (USA Boxing), so that Martiñon can compete in the tournaments. "Working with a woman is not easy," says Hector. "I work too hard, really hard. I don't want any excuses, because this is boxing." About his oldest daughter, Hector says, "She's something special." He and Jenny have three other kids, two girls, 2 and 13, and an 11-year-old boy. None of them boxes. The 13-year-old swims, and the boy plays soccer. When asked if Jenny thinks their youngest will take up boxing, she looks at the toddler and says, "No. I hope not." She explains that the process of training her daughter and sending her to tournaments in the hope that it'll all eventually lead to the Olympics requires too much money, time and energy to do twice. Local community group La Raza Roundtable has held fundraisers on behalf of Martiñon to help pay her way to tournaments across the country. "They do what they can," Jenny says, but continuing on a path to greater recognition means ever-increasing costs--tournaments can sometimes run around $8,000 each.

Fight Club

The most vivid proof that women can develop strength, endurance, and the will to win can be found in their battle to gain admittance to the Olympic Games. It took nearly a century for elite female athletes to fully pry their way in. --Colette Dowling, The Frailty Myth Outside the ring, Martiñon passes on pizza, ice cream and other traditional reasons for living. It's Raisin Bran, nonfat milk and a banana or oatmeal with toast and carrot juice for breakfast; turkey, chicken or tuna salad for lunch; and fish for dinner, recites Jenny, who prepares her daughter's meals. But it'll all be worth it if the International Olympic Committee adds women's boxing by 2004 or "definitely in 2008," Martiñon says. Unfortunately, that's not going to happen, according to Mike Moran, spokesperson for the U.S. Olympic Committee. "It could not be before 2012," he says. He explains that the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which controls the games' programming, "has been true to their word" and has abided by roughly a decade-old pledge to include women's events along with all new sports added to the Olympics. Women's wrestling, on the program for 2004 in Athens, is the most recent women's event to make the games, but, Moran says, "huge gains in women's weight lifting and wrestling [have] come at the expense of the men's sports." And men's wrestling is giving up one weight class to make way for women. The IOC is actually trying to slim down the Olympics, which has grown from 285 male athletes participating in 1896 to a newly instituted cap of 10,500 competitors nowadays. "After 21 years of remarkable expansion, the time has come for us to move from a period of continued growth to one of consolidation," IOC President Jacques Rogge said in a press release announcing the committee's November meeting in Mexico City. The IOC Program Commission's August report recommends the exclusion of several sports from the next two games because of low public interest, image problems, lack of global participation, judging difficulties and other reasons. Sports on the outs include baseball, the modern pentathlon and softball. Also endangered are the canoe/kayak slalom, equestrian eventing, one wrestling discipline and race walking. The report also discusses boxing, albeit in vague terms. "A number of questions have been raised by the public and within the Olympic Movement on the place of boxing in the Olympic Programme," the report states. It concludes, however, that the Olympics will keep boxing on the ticket and "will conduct further review" if necessary. Power Play While the IOC is tightening its belt, local boxing officials look at the broader picture of what it takes to get in the club. "I just think it's like anything else; it has to be proven," says Jeaneene Hildebrandt, chair of the USA Boxing women's committee. Hildebrandt, who is 62, was at the meeting in 1993 when the USA Boxing president made the announcement that "well, we have no choice; we have to make women's boxing a sport," she recalls. For women, boxing required two fights. The first was just to make it into the ring. The event, billed at the time as the World's First Women's Amateur Boxing Championships, took place in St. Paul, Minn., on May 12, 1978, one month after another first match was reportedly canceled. "A group of frustrated female boxers and their backers, prevented from appearing on Friday's slate [boxing card] ... are still bitter and plan to protest. 'All we asked for was four minutes on the card,' said [promoter Bill Paul], who wanted Joan Marcolt, St. Paul, and Debbie Kaufman, Minneapolis, to fight at Anoka's Fred Moore Junior High School for the state female bantamweight championship," according to a Minneapolis news report. The 24 intervening years have lent women's boxing some mainstream acceptance. International Amateur Boxing Association President Anwar Chowdhry, who makes recommendations to the Olympic Committee for event inclusion, was surprised by the high skill level of the women boxers at one recent competition, USA Boxing's Hildebrandt boasted. "If he did not think that the women should be in the Olympics, he would just say, 'I'm not going to present this to the Olympic Committee,'" she says. But he gave positive feedback and picked the tournament's outstanding boxer: a woman from Italy. Hildebrandt is confident that women's boxing will make the cut. "Every year, the skill level goes up, and there are more participants," she says. By all accounts, Martiñon is proof of the rising skill level. She's featured on the Women Boxing Archive Network's website as one of "the new kids on the block," a list she made before her recent 16th birthday. "Chris Martiñon, 15 years old, San Jose, Calif., has quickly made a name for herself in amateur boxing," the site states. It goes on to list highlights of her career: 90-pound female division champion at both the 1999 Boxers for Christ Championship in San Diego and the 1999 California State Golden Gloves held in Tulare, and dozens of other wins. She joins a growing number of girls and women who are serious about and good at the sport. "I know that there are a lot of younger and younger women getting involved," says Julie Goldsticker, acting director of media and public relations for USA Boxing. "There's a whole lot of youth movements, and it's extremely entertaining to see. They just keep going and going." USA Boxing's junior category includes kids ages 15 and 16. But at the local level, boxing organizations allow kids as young as 8 to fight. Alyssa Defazio was 10 when the Women Boxing Archive Network added her to its list of rising stars. "New wave of the future: Alyssa Defazio," the archive brags on her behalf. She was 4 feet 11 inches tall, 85 pounds and "a little spitfire that is one of many younger females getting into the sport." The first international women's boxing match was held in 1998 in Scranton, Pa., between Canada and the United States, according to the Women Boxing Archive Network. Another world championship was held in Turkey in November, where more than 30 countries participated, according to Goldsticker. But despite the fact that women's boxing seems to many in the boxing world to be closing in on Olympic entrance, it's not there yet. "It's definitely an uphill fight," Goldsticker says. Before an event can make it into the Olympics, it has to pass some tests. For women's summer events such as boxing, the sport must be "widely practiced" in at least 40 countries and on three continents. At least two world or continental championships must first include the sport.

A Long Way, Babe The Olympics began as a discriminatory event. The man who established the Olympic Games' charter, Pierre de Coubertin, staunchly opposed women's participation. "Baron de Coubertin firmly believed that the Games should traditionally remain a "eulogy for men's sport," according to the IOC's website. Meloponeme, a 19th-century Greek woman who ran a marathon in four hours and 30 minutes, according to the news of the time, as referenced by author Colette Dowling, was barred from the first modern Olympic Games, held in Athens in 1896. The effort to penetrate this all-male arena took some forward steps and then hit some walls. Seven female golfers competed in the 1900 Olympics. That was the beginning. Women participated in an archery exhibition in 1904. In 1920, women were allowed in swimming and diving competitions. But in 1924, the International Amateur Athletic Federation prohibited women from competing in the Olympics. The organization changed its mind in 1927 and let women compete in five events. Mainstream sentiment finally evolved from a time when Harper's Monthly Magazine, in 1929, protested the "animalistic ordeal" that was women's sports, and when The New York Times complained, in 1932, that the Olympic track field "was strewn with wretched damsels in agonized distress" to the more tolerant present. Now it's 30 years after the signing of the federal Education Amendments' Title IX's equal funding for girls' sports in schools and newspapers emphasize the toughness and punching power of female boxers. Often, the focus is on toughness tempered by traditional femininity. But despite embers of regressive thinking--like obligatory photos of boxer's applying makeup--punching is increasingly being viewed as an activity within the female realm of expression. And girls can take punches, too, without shattering, because they are training to use their physical strength. USA Boxing recognized women participants in 1993, after now-retired 16-year-old Washington state boxer Dallas Malloy, aided by the American Civil Liberties Union, sued the organization to let her fight--and won. Since then, women's boxing advances have continued. In 1995, the International Olympic Committee's Study Commission of the Centennial Olympic Congress established a Women and Sport Working Group. That same year, both the Golden Gloves amateur boxing tournament and professional boxing included women for the first time. The following year, the Amateur International Boxing Association (formerly the International Federation of Boxing) incorporated women's boxing. USA Boxing now has 2,000 women registered to fight in the United States, and the number of women in the ring is growing by leaps around the world. Women's boxing insiders like Hildebrandt and Martiñon were expecting to make it to the Olympics in 2004 or 2008. But according to the U.S. Olympic Committee's fact book, it takes seven years for a sport that's accepted into the Olympics actually to be added to the program. Women's boxing needed to be added as of last year to qualify for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. It wasn't, and the Beijing programming additions are now closed. "It's frustrating; it's certainly frustrating for a lot of the women who won't be able to compete due to the age constraints," says Goldsticker. If women's boxing makes the cut in 2012, Martiñon will be 26. Martiñon expects to stop boxing by the time she's 26. The age limit to compete in the Olympics is 34. "It's very difficult," Goldsticker says. "I know that they've been fighting this battle for a long time. I know that for [Martiñon] to have the patience and stamina to stick around for another 10 years. ... She's 16 years old, and I'm sure 10 years feels like an eternity for her. It's tough for a lot of the women." "We don't really know if they're going to have it or not," Martiñon says. "But we're getting ready for it."

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the December 19-25, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.