![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

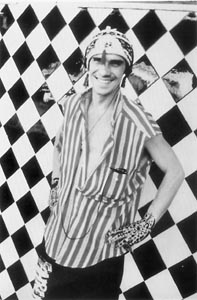

Latino Woody Guthrie: Manu Chao sings about the plight of refugees and border-crossers on his new album.

Latino Woody Guthrie: Manu Chao sings about the plight of refugees and border-crossers on his new album.

It Takes a Global Village Manu Chao brings the culture of the streets to 'Clandestino,' a mysterious, Latin-flavored 'Nebraska' By Gina Arnold A FEW MONTHS AGO, The New York Times ran an article exploding the myth of a Latin pop takeover. The story pointed out that aside from a few crossover acts like Ricky Martin and Jennifer Lopez, who sing and work in English, there's no real avenue for Latin artists on mainstream American TV or radio. And that's a pity, because not only is there a gigantic Spanish-speaking market in America and elsewhere, but given the global nature of today's pop music, with its mezcla of musical inflections from all over the world, an injection of foreign spirit into American pop culture would do a lot to liven things up. Moreover, in former times, there really was some truth to the idea that the best rock music came from America or England, but these days, it's not unusual for the whitest of pop acts to have lifted aspects of salsa, reggae and rai--sometimes balling them all into one number. Unfortunately, the fact that other countries have viable pop stars and amazingly catchy pop songs still seems to have escaped the notice of the mainstream music industry in America. There are, however, numerous huge talents in the global village, and tops among them is Manu Chao. Chao's 1998 album, Clandestino (Ark 21 Records), has been a slow-burning smash hit in both Europe and South America over the last two years, but despite its big overseas sales, its recent release in America has been practically ignored. An Internet search turned up no reviews of it in English, and one can see why: none of the rigid radio formats in America can find a place for a record that is not recorded solely in English. Record stores, too, have relegated Clandestino to the World Beat or Latino sections, rather than to Rock/Pop, where it belongs. It's all a big mistake, because Chao is much closer in spirit to Bruce Springsteen than to, say, Astor Piazolla. Back in the '80s, Chao headed the wonderful French punk band Mano Negra. I know, I know, the words "French" and "punk rock" sound really bad together, but trust me, Mano Negra were awesome, a sort of lighter-hearted, more energetic--and French-speaking--Clash, if you can imagine such a thing. Mano Negra, which called itself "an anarchist collective," broke up in 1993, after an ill-fated, French-funded tour of South American port cities by boat, and Chao spent the next four years wandering around South America and Africa, from Colombia and Brazil to Mali and Senegal. While there, he carried a tape recorder, taking down what he calls "the culture of the streets" via a series of mostly acoustic-based songs that attempt to capture the atmosphere of some of the places he visited. THE RESULTING ALBUM, Clandestino, sounds like a hipper and more mysterious, Latin-flavored Nebraska (the acoustic LP Springsteen recorded at home in 1981). The songs are filled with sonic immediacy, a "you are there" sensibility that's most unusual in today's overprocessed world of rock. In fact, Chao's solo record is a real original. It deserves to be a hit here as well as in Europe, and there's no reason why it shouldn't be. Clandestino even has songs in English on it--as well as in Spanish and French. (The singer, who is currently based in Barcelona, grew up in France but is of Spanish extraction.) Throughout, the language is simple and extremely understandable, from "Bongo Bong," a goofy song about a street musician, to "Je ne t'aime plus" ("I couldn't love you more"), a hushed love song that has the exact same tune. Chao, whose father, Ramon, is in fact a famous antifascist expatriate writer on the French paper Le Monde, clearly envisions himself as a sort of Latino Woody Guthrie. The title cut, for example, which is about the persecution of illegal African immigrants in southern Spain, is modeled on the Guthrie song "Deportee." "Desaparacido" is about "The Disappeared," or missing political prisoners of Chile. And "Welcome to Tijuana," which switches imperceptibly back and forth between English and Spanish, is about the sinister mess of trouble waiting for Hispanics on the border. Borders are an important concept to Chao: the record traverses many of them, and always from the outsider's point of view. For those who knew Chao in his role as the high energy singer for Mano Negra, however, it might seem odd that he could become so serious, so folky. In fact, it's a common pattern for punk rockers, especially ones who always saw their music as a political vehicle. Chao is merely following in the footsteps of Billy Bragg, John Doe of X, Mike Ness of Social Distortion, and many others, but he's doing it in a Latin way, which makes it more interesting--at least to me. That said, there is nothing trendy about Chao, even if this record has been playing in all the coolest cafes of Europe. He and his compatriots (currently, he tours with a band called Radio Bemba) are closer in spirit to the ultraserious and intellectual young men of the '30s and '40s who fought for socialism and against fascism. Today's "isms" may not be as obvious or as sinister as they were back then, but they're still there and still worth mentioning--even if these days, a freedom fighter's best way being heard is to mention them in song. One important point: Although "Clandestino" does contain traces of the frenetic, beat-happy work of Mano Negra, the overall tone of it is sad, even spooky. But the histories of South America and North Africa, where these songs were recorded, are rather sad, and Chao's work has always been politically motivated in the way that contrasts mightily with all the music coming out of America these days. Given how lame and emotionally flaccid most of that new music is, Chao--who will be playing his first gigs in this country in L.A. this month--is in a strong position to make a splash. America, you've been warned. At several points on the record, Chao uses the term "la ultima ola"--the last wave. Given the state of rock today, perhaps this really is it. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the December 21-27, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.