![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

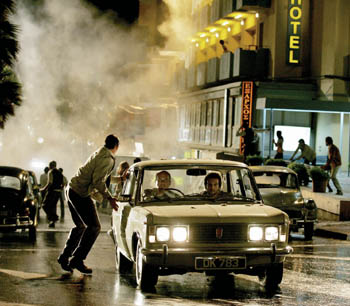

Street Beat: International hit men patrol the mean streets in 'Munich.' Payback Hit men track down the Olympic killers in Steven Spielberg's 'Munich' COMPETING with Syriana in the highbrow political thriller department is Steven Spielberg's Munich. Based on a loquacious Tony Kushner script, the film follows the hunting down of the Black Septembrists who engineered the Munich 1972 Olympic massacre, during which 11 Israeli athletes died senselessly. A payback plan is proposed by Golda Meir (Lynn Cohen), shrewdly portrayed as a yenta Queen Victoria. It is she who authorizes a squad of outside-the-law hit men to avenge the 11 dead. Leading them is an unlikely figure, a soldier and ex-bodyguard named Avner Kauffman (Eric Bana). He is under the command of paymaster Ephraim (Geoffrey Rush), who disavows all knowledge. The squad of avengers is paid through a never-empty Swiss account. ("Keep receipts!" urges a gesticulating accountant, a chunk of Brooklyn humor tossed in the mix.) Where the money comes from is a mystery; American taxpayers could hazard a guess. Avner organizes the freelance killers: a blood-thirsty South African (Daniel Craig), a Belgian maker of explosive devices (Mathieu Kassovitz) and an antiques dealer (Hanns Zischler). Despite his role as a recruiter, Avner is a passive figure caught in a quandary around authority figures, from Mrs. Meir to his own mother (Gila Almagor). Avner gets cut to size with the belittling dialogue that makes Jewish comedy what it is. Avner's hard-nosed, pregnant wife, hearing about the assignment that will keep her husband overseas, comments, "I'll put up with it—until I won't." Avner shuttles between powerful people: the spymaster Ephraim, Meir and, ultimately, a suave French intelligencer. The last is played Michael Lonsdale in a Camembert-ripe performance as a twinkling old paterfamilias-cum-killer—Don Corleone as a Frenchman. The film tracks a string of assassinations, but it worries over the question of moral authority. Avner's guilt afflicts his conscience. "Stop chasing the mice in your skull," he is advised. Was this advice ever handed to Kushner? Munich's script is a major mouse-racer. To keep us from losing sympathy for these hit men, Spielberg uses flashbacks of the Palestinian atrocity to propel the movie forward and to keep the audience in a vengeful frame of mind. Finally, he even intercuts between the killing and a scene of Avner atop his wife. The sequence looks like the oddest method of premature-ejaculation control yet devised. (For some, it's baseball scores; for others, it's the gunfight at the Munich airport.) What this movie needed wasn't a hero but an antihero. The Munich revenge hits may not have even targeted the right men, either, according to Time reporter Aaron J. Klein's new book, Striking Back. Spielberg's career-long tendency to choose the soft side is only amplified in the choice of his lead, Eric Bana. Might the commercial failure of Hulk have induced a crisis in Bana's self-confidence as an actor? He now seems like an actor waiting obediently for direction, a schlemiel strangely given a dangerous assignment. The decision to aestheticize the killings shows Spielberg's hand more than all the debate about the morality of revenge. The first target, a translator living in Rome, is stalked as he goes to the market. He carefully selects a bottle of milk and red cherries in a jar. Amateur artists in the audience may hope he purchases some mustard, too, to add some yellow to the field when this bag crashes into the ground, as we know it will. The assassination of a topless woman, with blood bubbling over her breasts, is about as close to sensuality as Spielberg gets. Spielberg supposedly learned his craft by breaking into Universal studios and watching the elderly Alfred Hitchcock direct. Although critics have been reaching for comparisons to Costa-Gavras, Munich is Spielberg's Topaz, an international thriller about a chain of assassins in which the mechanisms of death are more lively that the characters. There is quaintness in the Cold War�era equipment: a pre-cybernetic phone bomb and some plastic explosive that's either too weak or too strong. Munich almost functions as action cinema, but the force is diluted by conversations you can't believe you're hearing. Avner asks a Palestinian named Ali if he really does want his grandfather's chalky land back, with his much-wept-about olive trees. Later, the international hit men are made to realize it's not a cause but a home that they're all killing for. Worse, perhaps, is a flatulent pantomime scene that says, "Arab or Israeli, they both love Motown." Munich almost applies to the war on terror, in the typically guarded big-picture way. When even Spielberg feels like whispering, it shows how extreme our fearfulness has grown. But you can pick up a soft-spoken hint. In its margins, Munich demonstrates what John le Carré described in The Little Drummer Girl. There, a woman being turned out as a Mossad agent is consoled with "the kind of answers children want." Beware of those answers. Eventually, there is too much back and forth about righteousness (audiences just want to see somebody get it). One sits through the killings to learn that killings never solved anything—and, one supposes, that watching killings never solved anything.

Munich (R), directed by Steven Spielberg, written by Tony Kushner, photographed by Janusz Kaminski and starring Eric Bana and Geoffrey Rush, opens Friday valleywide.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the December 21-27, 2005 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.