![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

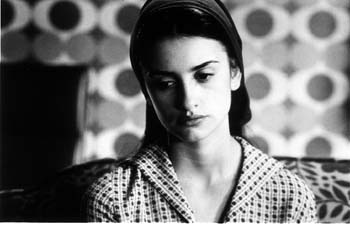

Nun of the Above Photo: Penélope Cruz plays a gorgeous sister in 'All About My Mother.' Maternal Instinct In Pedro Almodóvar's 'All About My Mother,' women can win respect and yet be completely undignified IT IS EASY TO TRACE director Pedro Almodóvar's influences. Helpfully, in his 13th and newest movie, All About My Mother, all of the director's debts to earlier movies are acknowledged upfront. This opus takes off from the treacherous backstage life of All About Eve, the emotional hysterics of A Streetcar Named Desire and the elegantly composed but deranged melodrama of Douglas Sirk's movies. So why does All About My Mother seem like such a glimpse of the future, instead of a retro-fest? Tracing the influences here are easy, but one could go nuts trying to trace the plot, which is worthy of a whole season on a soap opera. All About My Mother spins off from one of the director's feints in 1995's Flower of My Secret. Remember the emotion-choked scene in which the woman is requested to donate her brain-dead son's heart? And then, when the camera pulls back, it turns out that the scene is an instructional video? This time, Manuela (Cecilia Roth) enacts the scene in real life. She loses her beloved 17-year-old son in a traffic accident and is asked to give up the boy's heart to a clinic for transplanting. Grieving, Manuela decides to fulfill her son's last wish--to find out what became of his long-lost father, of whom Manuela never spoke. She goes to Barcelona, and that seaside city--shown to us in some iridescent aerial shots--seems like Wonderland. When she arrives, Manuela begins prowling around her old lover's haunts to flush him out. First stop: "The Field," a scary patch of wasteland where the chicks with dicks hang out, surrounded by the slowly wheeling cars of their johns. (Two of these transsexuals--one in black vinyl, one in white vinyl, both so glamorous that they practically evaporate--are seen in the distance squatting and playing patty cake in the dust.) Manuela rescues one transsexual whore who is being assaulted by a drugged-out boyfriend. The injured hooker turns out to be a dear old friend, La Agrado, "the pleasure" (Antonia San Juan). Together, the two pick up some new acquaintances, including a beautiful nun (Penélope Cruz) and the cast of a Spanish translation of A Streetcar Named Desire, in which Blanche and Stella are offstage lovers. Nina (Candela Peña), who plays Stella, has a junk habit. Huma Rojo (Almodóvar's regular star Marisa Paredes) is Blanche DuBois onstage, and the yearning Bette Davis in All About Eve offstage. Huma is a smoker's nickname; lovelorn, she takes it out on cigarettes. The gang helps Manuela look for Lola, the father of her dead son, who, as it turns out, went transsexual. Manuela gives an almost Transylvanian description of the promiscuous rat: "He was the worst of a man and the worst of a woman," a line that is undercut with a wisecrack--"Apart from the tits, he hadn't changed much." ALMODÓVAR LISTS the subjects of this film in the press notes: "The capacity of women to playact, to fake. And wounded maternity. And the spontaneous solidarity between women." It's a sure thing, as certain as the fact that a puking woman on screen is pregnant or a coughing woman on screen is going to die--a sure thing that the female qualities of solidarity and silence are almost always played as treacherousness or weakness. Almodóvar's admiration for female fluidity and adaptability is the opposite of Tennessee Williams'. In Williams' plays, womanhood lies quivering and helpless under the feet of Man the Brute. All About My Mother is also opposed to the themes of Joseph L. Mankiewicz's All About Eve, in which it's every woman for herself. The trouble with the commonplace middle-aged-woman movie--exemplified by the awful The Love Letter--is the insistence on the dignity of the women despite their own faults. By contrast, Almodóvar's women can win respect and yet be completely undignified. And Almodóvar's sympathy and amiability make the film sweet: un agrado. The coolness of the storytelling doesn't undercut the characters' dilemmas. What sounds like soap-operatic farce is deepened by the acting, and Almodóvar delights in the handsomeness of these women, self-made or otherwise, especially in a moment when they gather on a couch to polish off some Spanish champagne. These women, who might pick women or men or transsexuals to love, are the heart of a film in which gender doesn't really matter anymore, and what could be more modern than that? This undertone of freedom is the reason why All About My Mother skunked even the brilliant The Dream Life of Angels at the L.A. Critics awards. That's unfair, really, because the two films are so different--but understandable, because this is a damned good movie.

All About My Mother (R; 101 min.), directed and written by Pedro Almodóvar, photographed by Affonso Beato and starring Cecilia Roth and Marisa Paredes, plays at Camera 3 in San Jose and the Guild in Menlo Park. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the December 23-29, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.