From Agony to Myth

Director Atom Egoyan confronts mortality in The Sweet Hereafter

LIABILITY LAWYER Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm) travels to the snowy hamlet of Sam Dent in the mountains of British Columbia. The town has been devastated by a school bus accident in which 22 children drowned. Stephens is trying either to make a buck or to establish order over chaos, and under the lens of Canadian director Atom Egoyan in The Sweet Hereafter, we're never quite sure which.

Anyway, Stephens has been a lawyer so long that he doesn't know the difference between the demands of morality and the demands of his business. "There is no such thing as an accident," Stephens assures the townspeople, urging upon them the notion that someone, somewhere is liable for the catastrophe. Saying that, Stephens has to blind himself to the way he might have swerved to avoid a crash in his personal life.

We play this game at home, scanning the obituary pages and making up reasons why the reaper caught them instead of us. It's our way of trying to handicap numbers in a lottery we're all going to win someday. But Egoyan shows the people of Sam Dent as faulty and yet free of blame. He observes adultery as a taste of sweetness in a pair of tragic lives. And this is the first movie in a long time to treat incest as a terrible mistake instead of a terrible sin.

Egoyan's script, based on Russell Banks' novel, has poetry to it--not airy-fairy lyricism, but the strong, morose confrontation of mortality found in W.H. Auden or Philip Larkin. The people of Sam Dent are rural men and women who don't spill their guts. Their pain goes without saying, but it's said as if with slips of the tongue.

Gabrielle Rose, as Dolores Driscoll, the sweet-natured driver of the doomed bus, has a casual comment about the farm animals at a dismal country fair. A moment passes before you realize that what she says about them--"No matter how many ribbons they've won, these animals don't like being here"--is true for much of the human race.

This all sounds depressing. Maybe I'm perverse, but I didn't think there was a depressing moment in this movie. There's too much anger in The Sweet Hereafter for that, and it's so well made that you spend the time marveling at its strength rather than weeping for the dead. Egoyan's text ends powerfully, remarking on the unkillable quality of hope.

The storytelling is as fine as the story; Egoyan uses flash-forwards that are as smooth as dissolves. Paul Sarossy's cinematography is an example of why Cinemascope was created. Ian Holm adds another superb performance to a résumé crowded with them. As we watch Holm compose himself in the mirror of an airplane bathroom, we see a demonstration of the difference between an abject man and a ridiculous one.

THE CAST includes the smoky-voiced Alberta Watson (the mom in Spanking the Monkey) playing a straying wife. Watson makes sorrow look absolutely aphrodisiacal. Director Egoyan's own wife, Arsinée Khanjian, plays the shaggy mother of a dead child--and except for some scenes in Mike Leigh's High Hopes, no film has so effectively conveyed the stubborn dignity of hippies long out of their time. (And the hippies provide a wicked joke, which isn't on them--surprise. Since they sit on the floor, Stephens must persuade them on his knees.)

Sarah Polley plays Nicole, the only child--an adolescent, actually--to survive the crash. Her reading of Browning's The Pied Piper of Hamelin changes the disaster from agony to myth. Polley, who was Sally in Terry Gilliam's The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, makes the biggest impression by a young performer since Uma Thurman in Dangerous Liaisons.

As in Egoyan's 1991 film, The Adjuster, the forces of Insurance--our faith is in Thee--are neutral, possibly malign. Representing Insurance, these agents and lawyers who make us enumerate our gifts and describe our debts have the remoteness and power of Old Testament angels.

Egoyan has said that The Sweet Hereafter is a sort of Western: a stranger comes to a guilty town isolated under a big sky. I think it's more of a film noir. As in the finest noirs, the mystery is not who is the murderer? The mystery is who, or what, is killing all of us? The Sweet Hereafter is charged with the power of classic Hollywood mysteries, and we're left tantalized by the unanswered questions, not teased. The Sweet Hereafter is the best movie of the year.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

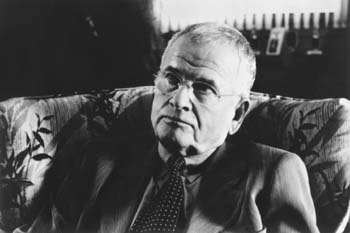

Holm, Sweet Holm: Ian Holm plays a conflicted lawyer intruding upon a town's grief in Atom Egoyan's new film.

The Sweet Hereafter (R; 110 min.), directed and written by Atom Egoyan, based on the novel by Russell Banks, photographed by Paul Sarossy and starring Ian Holm and Sarah Polley.

From the December 24-31, 1997 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)