Big Bang

Stories from 1996 the mainstream press couldn't resist blowing out of proportion.

By Michael Learmonth

LAST YEAR Americans told Congress to shut up and play nice, while Richard Allen Davis let us all feel ducky about the death penalty. It was also the year Tupac Shakur became a symbol when he became a statistic. And a little green croc in San Francisco captured our hearts before he was captured on the evening news. Remember these stories? Remember wondering why the media wouldn't let them go away?

Ethics Attack

THE YEAR BEGAN uneventfully enough. The election had long since become a mano-a-mano snooze-a-thon between Clinton and Dole. The pundits were busy trying to figure out how to make a story of it. Then, a bomb hit Barnes & Nobles in the form of an immediate bestseller called Primary Colors, a novel written anonymously that bore stunning resemblance to the inside dish on the Clinton-Bush contest of 1992.

The Washington press corps immediately decided that the perpetrator of the hottest book of the election season must have been, gasp, one of them. It was just too real. But, then, it was also much too well-written. Who could have been capable of this? Garry Trudeau? Mark Halprin? Sidney Blumenthal? No less than three Newsweek reporters made the suspect list. One of whom, Walter Shapiro, reflected the views of many of his colleagues when he said in his review of the book, "Words cannot describe how much I wish I had written it."

Finally, after many denials Newsweek reporter and former New York Magazine writer Joe Klein was fingered when the Washington Post obtained an early draft of the book and gave it to a handwriting analyst. Klein, a reporter for the nation's second-largest news digest, had lied to his editors, to his readers, to the nation. Then came the ethics hand-wringing. Nothing like a multimillion dollar book and movie deal to make the Washington press corps introspective. Earth to Washington press career-hounds: the rest of us could hardly care less.

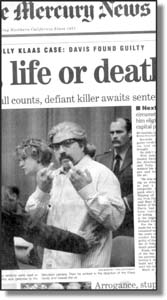

Richard Allen Davis

THE LOCAL PRESS CORPS could hardly believe its good fortune when the trial of death-penalty poster- boy Richard Allen Davis was moved from Santa Rosa to San Jose. Judge Thomas Hastings wisely banned cameras from the courtroom to avoid a media frenzy on the scale of the Simpson trial. But that didn't stop the daily reports from the courthouse steps. And it didn't stop "the gesture" from making the front page of all the local dailies. Remember him as the killer who elected a governor. A one-man argument for "three strikes." If top cop Dan Lundgren makes it to the governor's mansion, he'll have the media-savvy Davis to thank. That sicko's front-page antics on the day of his conviction will be worth 1,000 Dennis Perons when the attorney general hits the campaign trail. Having thrown both state houses solidly to the Democrats last November, it seems likely Lundgren will surf into Sacramento on two of California's most reliable voting patterns: ticket-splitting and crime phobia.

Croc Attack

BUT JUST WHEN EDITORS and news directors were running out of "brights" to balance our daily appetite for Davis updates, a crocodile was spotted in the Presidio's Mountain Lake on July 24. Brights are those uplifting little stories every newspaper and television newscast has. So essential are they to news culture, the Associated Press tests would-be reporters on their skill in writing these quick-and-happy stories. Call the Presidio Croc the bright of the year. Every day San Francisco's Nessie was at large was a great day to be a producer or an editor. So determined were the local papers to keep Nessie in the news, the Chron imported a gator expert from the Everglades. William Randolph Hearst cracked a smile in his grave when Examiner editor Phil Bronstein tromped around the water's edge in a wetsuit. The first week, it was funny. Then it became a little silly, but that was the point. Ten weeks later, amid fears of disappearing swans, the little bugger was lured out of his lair by a two-dollar piece of meat. All right, everyone, on three: awwww.

Tupac Shock

THE DEATH OF Tupac Shakur in a hospital in Las Vegas gave the press another opportunity to skewer a boogeyman that's been bugging them for ten years--gangsta rap. Tupac's story was irresistibly poetic. And there were few signs of resistance at the Merc, which jumped at the opportunity to make a point about music's connection to violence. Merc columnist Angelo Figueroa even turned out a sanctimonious rap of his own: "He was a modern-day beatnik with a pistol in his mike/ promoting a lifestyle I strongly dislike"...you get the picture. The reality, to the great consternation of moralists and columnists alike, is that Tupac was neither victim nor villain. He was self-obsessed. He spoke out of both sides of his mouth on violence to suit the moment, and simply filled the niche that millions of moneyed record consumers gave him.

Civil Drivel

BUT THIS WAS ALSO the year that the pundits broadened their search for America's malaise from rap lyrics and violence on television to something far more broad and less disputable: a national erosion of civility. Regaining the country's lost "civility" became a cause célèbre for everyone from Ellen Goodman to Rush Limbaugh. The obsession trickled into the elections, with Clinton and Dole both jumping on the civility bandwagon, seemingly competing in the debates for Mr. Congeniality instead of Mr. President. Clinton obsessively praised Dole's war record. Dole cracked self-effacing jokes.

The media just played along and trumpeted the "conventional wisdom" that Americans are tired of dissent, tired of nastiness--tired, in fact, of issues. At the National Press Club, Judith Martin, a k a Miss Manners, summed up election '96 as "a pro-civility landslide." But what happens when civility becomes an end in and of itself? What happens to the intrinsic function of political campaigns? When Americans have grown tired of debate, they've grown tired of democracy.

The national civility fad was reflected in a status-quo election. Clinton was handily reelected, as were most of the members of the infamous House freshman class of 1994. In the meantime, the local press missed the biggest story of the election: huge unexpected Democratic gains in the state assembly, giving them a seven-seat majority. This, in spite of the seemingly contradictory landslide for Proposition 209.

Fried Wired

FOR THOSE OF US suffering from media-web-hype fatigue, 1996 brought some token consolation. Just when it seemed every company with a web address could become the next Netscape, Pixar or Yahoo on Wall Street, the company that publishes Wired magazine, in large part responsible for hyping the Internet, twice aborted plans for its own public offering. The first time, last spring, the company valued itself at over $450 million. The second time, in the fall, it dropped a planned offering of $250 million. The company that chronicled the rise of the web and prided itself on forecasting the future of the Digital Age simply missed the boat. To be fair, the symbolism of Wireds failure outstrips the circumstance. Wired has never been more than a profitable magazine and a bunch of "new media" enterprises that have helped it lose $48 million in four years. Even so, this Wall Street rejection will mark the day when the bulls stopped running for web companies. For all of us sick and tired about reading the "Internet startup hits pay dirt" story, Wireds loss was our gain.

Media Conspiracy

THE NEXT OPPORTUNITY for the media to examine itself came in midsummer, when a boomtown paper with national aspirations broke what, initially, looked like the story of the decade. The Mercs "Dark Alliance" series started on Aug. 18, which established the connection between the father of crack pushers, Freeway Ricky and leaders of the murderous, U.S.-backed Contra rebels in El Salvador. The story had been told anecdotally before, but reporter Gary Webb brought damning new evidence to the table.

Needless to say, the wannabe Woodwards and Bernsteins at the big daddies (the Washington Post, the L.A. Times and the New York Times) were having none of it. They spent hundreds of inches obsessing over the story's alleged holes and inadequacies. While L.A. based U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters called for congressional hearings, the debunkers squabbling fell into three sour-grapes categories: we already reported the story, the Merc overstated the story and it's not a story. In chronicling the Washington Posts effort to trash the Mercs Watergate, Washington City Paper editor David Carr wrote, the Mercs "biggest sin was breaking a story without the permission of the big boys."

Editorial Dependence

Despite the editorial courage the Merc demonstrated in publishing Webb's series, the company that owns our hometown daily undercut its credibility and violated the trust of its readers by making a donation to the effort to defeat Proposition 211.

Knight Ridder, owner of the Merc and the second-largest newspaper chain in the country, gave $50,000 to defeat the proposition that would have made publicly held companies more vulnerable to legal action by shareholders. It was vehemently opposed by everbody who's anybody in Silicon Valley. And the Merc wants desperately to be somebody. Opponents said 211 would cripple companies in risky high-tech industry. Now both the Merc and its chain are vested in the success of the boomtown of the Digital Age, but the question remains why it would sacrifice the all-important appearance of impartiality on an initiative that was getting stomped anyway. The proposition lost by 50 percent. Its opponents raised about $30 million more than its backers. Foes of 211 raised so much money they simply couldn't spend it all and decided in the final days to spread the wealth to the wealthy consumers of their products by donating to the campaign against Proposition 217, which would raise taxes for those making over $115,000. Perhaps Chairman Tony Ridder should have checked the polls before he opened his checkbook. Or maybe he wanted to show solidarity with the Mercs high-tech benefactors. In the end, Knight Ridder showed it cares more about protecting its business interests than protecting the public's trust.

Year Fear

THE NEW YEAR is the time when publications all over the country submit to the urge to tabulate, evaluate and pontificate on the year gone by. But if you think taking authoritative stock on a year or even a decade is a journalistic conceit, just wait until the hacks get their hands on the millennia. Consider the possibilities: Dan Rather speculates on how Jesus measures up to other community activists or Ghengis Khan to modern-day warmongers. Yes, the media is gonna party like it's 1999--for the next 36 months. Get ready. It could get ugly.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

From the Dec. 26, 1996 to Jan. 1, 1997 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)