![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Obscene Gesture: With Breakbeat Era, Roni Size situated drum 'n' bass back where it began, on the side of chaos, not complacency. Mainstream Subversion Who's converting whom? In 1999, the mainstream co-opted electronica, but innovators like Moby kept the underground sound fresh By Michelle Goldberg OLD RAVERS can still remember the days when electronic music seemed subversive. It was the early '90s, the country was in--remember?--a recession and the mainstream was gorging on grunge, a fad that had been recently sucked up from its underground. Teenagers were reminded daily that they couldn't ever expect to earn as much money as their parents did or have has much fun as kids did decades earlier. House and techno music exploded into America as a day-glo revolt against the drab fallout of the '80s. Walking into a dark, pulsing warehouse as liquid-limbed boys and glittery girls throbbed together to a whole new kind of music, gobbled e's and lollipops, and grinned maniacally, one felt the defiance of insisting on joy in the midst of widespread depression. These kids, with their iconography of cartoons and aliens, seemed to be willing themselves simultaneously into the future and the past, dreaming that the next millennium would restore them to some fantasized bucolic childhood innocence. It was a naïve dream, but after years of hearing about other generations' raptures, to see the sun come up with your hands still waving in the air was truly very heavenly. Cut to 1999. The Orb undulates dreamily in a Volkswagen commercial, bhangra-junglist Talvin Singh provides the soundtrack to a spot for recordable CD players. Electronic music has been wholly assimilated into the mainstream--more wholly, in fact, than genres like psychedelia, punk, New Wave or hip-hop ever could have been. Largely lyricless and nonnarrative, rave music once seemed like a utopian revolt against rock's cult of the individual, but clever admen realized that, without a distinct message of its own, electronic music is easy to appropriate. At the same time, the past two years have seen mainstream musicians using beats and loops to infuse their songs with fresh energy: Madonna's Ray of Light, Cher's Believe, Tori Amos' To Venus and Back. Even the upcoming Axl Rose album is reported to be laced with breakbeats.

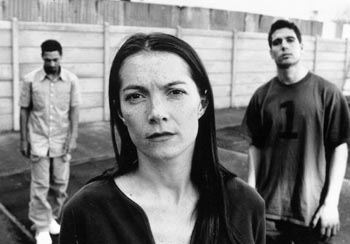

Photograph by Corinne Day

BUT WHILE the mainstream's lucrative embrace of electronica has sucked some of the vigor out of the underground, pop has benefited enormously from its electronic influences. By teaming up with producer William Orbit, Blur produced 13, a watershed album for the fusion of rock and electronica. Combing the structures of ambient and abstract jungle music and the lyrical passion that is rock's greatest trump, 13 was a huge leap for the boys once content to catalogue the social structures of Merry Old England. The track "Bugman" sounds like early Iggy Pop remixed by DJ Spooky, and it's enough to convince even the most avidly anti-guitar types that rock indeed has a future. On the debut album from Le Tigre, former riot grrl Kathleen Hannah created dance music as incisive as it is catchy. "What's Yr Take on Cassavettes," is the one of the smartest dissection of the gender wars in the history of pop. Former Throwing Muses singer Kristin Hersh also went a bit electronic on Sky Motel, which was aglow with feedback cascades, pulsing drum loops and sampled nature sounds that suggest a vast, empty night. Dot Allison, the former lead singer of the band One Dove, released the gossamer Afterglow, an album that sounds like the angel child of Portishead and the Cocteau Twins. Even folkie Ani DiFranco incorporated a bit of machine music into her brilliant 11th album, To the Teeth, on the track "Swing," which is flavored with scratching and even guest MC vocals. At the same time, the banalizing mainstream has forced the best DJs and producers to find new sources of inspiration for their music, resulting in some of the most stunning records of this or any year--albums like Moby's Play, Breakbeat Era's Ultra Obscene and the Basement Jaxx's Remedy. The most interesting of these is Ultra Obscene, both because of its fierce, arresting passion and because it suggests a way for drum 'n' bass to transcend its mainstream role as a kind of dystopian Muzak, a cheap signifier of urban edginess. With drum 'n' bass, the cycle from conception to co-option was faster than with any music in history. It went from the deepest subcultural depths onto the soundtrack of corporate America without even the usual stops on MTV and radio playlists. With Breakbeat Era, drum 'n' bass demigod Roni Size situated the music back where it began, on the side of chaos, not complacency. Ultra Obscene is a difficult, disturbing, claustrophobic record, but one with spacey atmospherics, a hot groove and enough submerged melody to counteract its masculine, martial percussion. What truly sets the album apart, though, is the Bristol diva Lennie Laws. Her voice is raw and coiled as if she hasn't slept for days, and ironically, her lyrics help the music recapture some of jungle's old insurgence. A line like "Now that you suffer from our disease can you understand me?" from the creepy "Our Disease" will never move units. While Ultra Obscene put some of the fear and loathing back into drum 'n' bass, the Basement Jaxx brought a healthy helping of love back onto the dance floor. Outside certain underground club scenes, the funked-up, multicultural gay vibe that spawned genres like house and garage largely faded once the geeky white boys took over. Then, with Remedy, two geeky white boys brought it all back, creating an exuberant, ecstatic record so sexy and organic it seems suffused with the sweat of a hundred all-nighters. Full to bursting with grandiose builds and addictive hooks, Remedy rekindled the optimistic bliss that can make dancing all night feel like redemption, at least until the next workweek begins. FINALLY, THERE WAS Moby, whose 1991 single "Go" ushered in the era of the electronic-music superstar. Just as he began the decade by pushing dance music into the future, he ended it by connecting techno to its roots. His latest album, Play, does more than any record in history to connect electronica with a profound American tradition, fusing breakbeats with samples from gospel and blues field recordings. Moby's career has been heavily marked by the unease that electronic-music purists feel about the genre's inevitable mainstreaming. One of the first techno stars to gain fame beyond the underground, he also has done much to bridge the divide between rock and dance music, most notably by his unapologetic use of guitars in his beat-based compositions. Thus by the mid-'90s, many electronic-music fans shunned Moby as a sellout. The stunning Play may not restore his credibility with nightclub elites, but it cements his place as one of the most important artists of the decade. Sure, there will always be those left heartsick and bitter as their scenes are expanded, diluted and co-opted. But just as rock & roll was born of the collision between blues and country, and techno was created by the strange convergence between the Teutonic pulse of Kraftwerk and the electro rhythms of the Bronx, the best pop has always been mongrel music. With his genius for hybrids, Moby embodies the direction electronic music took in 1999. The postmodern era, as every liberal-arts major has heard a thousand times, has been all about fracture and disunity, and electronic music, with its collage aesthetic and abstract structures, is often used to signify our disjointed times. But as artists like Moby prove, the most enthralling albums of 1999 have been more about synthesis than splitting, about erasing boundaries instead of creating them. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the December 30, 1999-January 5, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

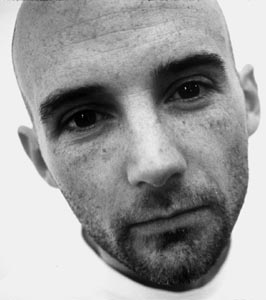

On the Go: With his album 'Go,' Moby connected techno to its musical roots.

On the Go: With his album 'Go,' Moby connected techno to its musical roots.