Sam Quinones

Squeeze Art: Eduardo Hernández of Los Tigres

San Jose's Los Tigres del Norte have remade Mexican pop music twice over

By Sam Quinones

JORGE HERNÁNDEZ was an 18-year-old accordionist, recently arrived from Mexico and living in San Jose, when he heard a woman in a nightclub sing a song about two drug runners. The song unfolded like a film. It told the story of a man and woman--he an illegal, she a Chicana from Texas--smuggling marijuana from Tijuana to Los Angeles. After exchanging the dope, the man says he's taking his money to visit his girlfriend in San Francisco. His partner, however, is in love with him. Unwilling to share the man with another, she shoots him in a dark Hollywood alley and disappears with the money.

Hernández asked if his band--which included his brothers and a cousin--could record the song. Los Tigres del Norte released "Contrabando y Traicion" (Contraband and Betrayal) in 1972. America's youth were getting high in large numbers, and Mexican immigrants were seeing drug trafficking daily as they crossed the border. The song hit huge, kicking off one of the most remarkable careers in Spanish-language pop music.

Since then, Los Tigres del Norte, out of their home base in San Jose, have made 30 records and 14 movies, won a Grammy and changed Mexican pop music twice. Their newest album, Asi Como Tu, came out this December.

The band members live in San Jose and Morgan Hill almost anonymously. Yet they are probably the most renowned musicians in this area, and most weekends, they can be found anywhere from New York to Guadalajara playing concerts for thousands of fans.

Los Tigres del Norte--now four brothers, a cousin and a friend--are the Mexican immigrant experience personified. Like thousands of immigrants, they crossed the border and made it in America but never shed their most precious commodity, their Mexicanidad--their Mexicanness. Like the Mexican-immigrant community, they are virtually unknown to American society at large. Within that community, they are revered--Los Idolos del Pueblo.

Los Tigres have twice created trends in Mexican pop music, first with songs about drug smuggling and later with immigration songs. Immigrants, in turn, transported their music to parts of Mexico where the band was unknown. Los Tigres' audience now stretches across the U.S. and down to the Mexican states of Michoacan and Guerrero and into Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua--places where people's first contact with norteño music was at a Tigres dance in Redwood City or Visalia.

Together, the band and its public turned norteño music into an international genre. Meanwhile, the band modernized the music, infusing it with boleros, cumbias, rock rhythms and waltzes; sound effects of machine guns and sirens; and better recording quality. In the process, they made a pop style out of an accordion-based polka music indigenous to dusty Northern Mexico cantinas.

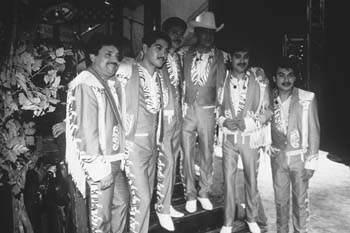

Sam Quinones

Los Idolos del Pueblo: Eduardo (left) and Jorge Hernández

LOS TIGRES emerged from an unnoticed side of the 1960s. As America's restless children were turning to drugs and music in rebellion, restless working-class Mexicans began coming to the U.S. Their exodus was also a rebellion of sorts, if unarticulated and unpublicized. Mexico's young were leaving corrupt Mexico--the Mexico behind the sunglasses, the Mexico that never gave a poor man a chance--eager to recreate themselves in the fields and restaurants of gringolandia. The irony was that in gringolandia these immigrants wanted more than ever to be Mexican. They missed the pueblo, a girlfriend, mom. Mostly they asked from the U.S. what Mexico had never allowed them: a chance to earn real money for hard work, to progresar.

As these immigrants grew into one of the most important movements of people in the last half century, Los Tigres became their chroniclers, spokesmen for a community that remains largely voiceless in Mexico and the U.S. Their best songs distill the essentials of Mexican working-class life: brutal machismo, piercing irony and the tenderest melodrama.

In 1968, they arrived at the border from the Pacific Coast state of Sinaloa, a kid group hired by a promoter to play the Mexican Independence Day parade in San Jose and to perform for the prisoners at Soledad. Since the oldest member was only 14, they had to convince a middle-aged Mexican couple to pretend to be their mother and father. The band had no name. But the immigration officer kept calling them "little tigers," and they were headed north and playing norteño music, so they became Los Tigres del Norte.

Los Tigres never returned to Mexico to live. After the parade, the promoter took them to play Parque de las Flores, on Keys Street, where San Jose's Mexican community congregated on Sundays. The band was only looking to make some money for the trip back to the border. But the show was broadcast over the radio and heard by Art Walker, an Englishman from Manchester who spoke not a word of Spanish but who would become one of the great impresarios of Mexican pop music in California.

Walker had a record distributorship downtown but wanted to start a record company. Los Tigres were his initial signing to Walker's Fama Records, the first and, for many years, the most important Spanish-language record company on the West Coast.

Walker bought the band members instruments, gave them music lessons and suggested that they use electric instruments. "We never thought you could play norteño music with a full drum set and electric bass," recalls Hernán Hernández, the group's bass player. "That was for modern groups, rock groups."

San Jose was still a city where Mexicans daily felt the brush of racism. "We really had to battle to eat," says Hernán Hernández. "They wouldn't serve us in stores or restaurants."

Still, San Jose was becoming a good place for a young Mexican band. It was growing rapidly, and so was its Mexican community. "During the late '60s and '70s, the social infrastructure of the Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant communities developed significantly," says Jesus Martinez, a political science professor at Santa Clara University, who grew up in San Jose and first saw the band at a furniture-store opening downtown during these years. "There were a lot of bars they could go to. There were more businesses. There were radio stations to disseminate their music. There were more places for them to be hired."

THE BAND MEMBERS lived in a room in the house of a Mexican woman. For the next few years, they played for the Bay Area's growing Mexican community. "Contrabando y Traicion" gave them their break and established Los Tigres in Mexico for the first time.

They began returning home to play. The song became a norteño classic, recorded by dozens of lesser-known bands. Its two characters, Emilio Varela and Camelia la Tejana, are now part of Mexicans' cultural vocabulary. Historically, the song is also remembered as the first hit about drug smuggling. Los Tigres followed it with "La Banda del Carro Rojo" (The Red Car Gang).

Together, the songs revealed a market and essentially created the narcocorrido, which is currently undergoing an explosion in popularity in Mexican music. The narcocorrido updated the traditional Mexican corrido, or ballad, which told of revolutionaries, bandits or a famous cockfight. Instead, narcocorridos tell of drug smugglers, shoot-outs between narcos and police, betrayals and executions.

Almost any norteño band nowadays plays a few; hundreds of bands play nothing but. Narcocorridos are Mexico's gangster rap. Both musics recount horrible violence, and both receive virtually no radio support--nonetheless, both maintain enormous audiences.

Catholic Church spokesmen and Mexico's center-right National Action Party have criticized the narcocorrido phenomenon, and the groups that play them, as part of "the culture of death."

"The only thing that we do is sing about what happens every day," Jorge Hernández says. "We're interpreters, then the public decides what songs they like."

The public has always decided it liked the dope songs. For many years, the band included two or three on each album. In 1989, they put out Corridos Prohibidos (Prohibited Corridos), an entire album about drug smuggling that caused an uproar in Mexico and the immigrant community in the U.S. There were reports that narcos were buying the record by the case.

Still, Los Tigres try to distance themselves from the hundreds of cookie-cutter narcobands that have sprouted up over the last 20 years. Their repertoire has always been at least half love songs. "Un Dia a la Vez" (One Day at a Time), a quasireligious tune, responded to the growing influence of fundamentalist Protestant churches within the Mexican immigrant community in the mid-1980s--churches that were condemning dancing and singing as indecent. They won their Grammy for "America"--a rock anthem expounding the universal brotherhood of all Latins.

Los Tigres reside by choice on the tamer side of the narcogenre. Unlike younger bands following them, they only occasionally mention the names of real drug smugglers, are never photographed with pistols or assault rifles, never curse in a song and usually refer to marijuana and cocaine as hierba mala and coca.

"[Narcos] have sent me letters, notes," says Jorge Hernández. "They invited us to meetings years ago. We've never had the opportunity, nor wanted to meet them. We've made our career in public, not at [private] parties."

Sam Quinones

Mis Dos Patrias: Los Tigres sing about lives divided between two countries.

THEIR EXPLORATIONS of the narco theme brought them fame, but Los Tigres earned a lasting transcendence when their songs began reflecting immigrants' conflicted feelings toward their new home. Their first effort at the subject was "Vivan los Mojados" (Long Live the Wetbacks)--recorded in 1976, well ahead of its time. The song wonders what would happen to America's crops if all the mojados were suddenly sent home. Within the Mexican immigrant community, the reaction to the song was electric.

In the early 1980s, Los Tigres hired as their producer Enrique Franco, a musician and composer who had just arrived from Tijuana. The collaboration with Franco would give Los Tigres their most enduring and bittersweet immigration tunes, roughly coinciding with the U.S. debate over the immigrant-amnesty law, which Congress passed in 1986.

"Pedro y Pablo," "El Otro Mexico" (The Other Mexico) and "Los Hijos de Hernández" all deal with the yearning to return home, love lost through separation and the economic importance of immigrant labor. In 1988, as war was sending thousands of Central American immigrants to the U.S., Franco wrote "Tres Veces Mojado" (Three Times a Wetback)--a story of a Salvadoran refugee who crosses three borders to get to America.

Franco's greatest immigration song of all, the one that changed the genre, came in 1984. Up to that point, songs about immigrants were usually novelty tunes about the zany high jinks of clever immigrants outfoxing the dull-witted migra.

"[Immigration] had never been treated as a social problem," says Franco, now a record producer in San Jose. "I was illegal at the time. I never had the problem of communication with my children, but many immigrants do. There isn't time to talk to the kids. The children learn another language. That's where the gap between kids and parents begins."

"La Jaula de Oro" (The Gold Cage) is told by an immigrant years after he outwits the migra. He's discovered that he doesn't feel at home in the country he tried so hard to enter. Even worse, his children now speak English and reject their Mexicanidad. And though he aches to return home, he can't leave his house for fear he'll be deported.

The U.S. "is a gold cage. You have everything. You live well, you have comforts," says Jorge Hernández. "But it's another type of life, very different from ours. ... The United States is very solitary. And you can't relax, like here [in Mexico]. There's not a lot of heart in the family. When the child reaches 18, he leaves the family."

By the early 1990s, the band was playing somewhat fewer narco and immigrant songs. But the nature of current events has returned a harder thematic edge to their music. In 1995, they recorded "El Circo" (The Circus) about former president Carlos Salinas de Gortari and his brother, Raúl, now in prison on murder and money-laundering charges.

The title song of Jefe de Jefes (Boss of Bosses), released over the summer (and recorded locally at the Music Annex studios in Menlo Park), is about a fictional drug kingpin. The album features several narcocorridos, including one about drug lord Hector "El Guero" Palma, arrested after a plane crash in 1996. "El Prisionero" is about the recent political assassinations in Mexico.

As anti-immigrant sentiment has intensified in California and the country, the band again touches the concerns of its most important audience. "El Mojado Acaudalado" (The Wealthy Wetback), also from Jefe de Jefes, is about immigrants who've made it in the U.S. but no longer feel comfortable and are going home with heads held high. "Mis Dos Patrias" (My Two Countries) has a Mexican character who, during his naturalization process, insists that he is not a traitor to his flag, that he's only protecting his pension.

Yet another song perhaps best sums up the feelings of immigrants these days. "Ni Aqui ni Alla" (Neither Here Nor There) is doused in pessimism brought on by America's anti-immigrant atmosphere and Mexico's economic crisis and corruption scandals. The song doubts immigrants' chances of receiving justice or of being able to progress in either country.

It is a philosophical U-turn for a band whose music and career have been founded, like the immigrant community itself, on a healthy optimism and belief in the healing powers of hard work.

"You have to tell the truth. We're not good here or there," says Jorge Hernández. "You never know if making money and living right, you're going to make it."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)