In Phillip Hua’s art practice, Atlas, a 13-foot-tall tree, signaled a definitive change in his approach to scale. When Hua and I spoke about “You Can Never Go Home Again,” his first solo exhibit at the Triton Museum, he recalled, “At the time, I was working in a frame shop where you’re always thinking about conservation of the artwork.”

The colorful tree at the center of Atlas is an inkjet monotype, wrapped in transparent packaging tape and distinctively mounted on newspaper spreads from the Wall Street Journal.

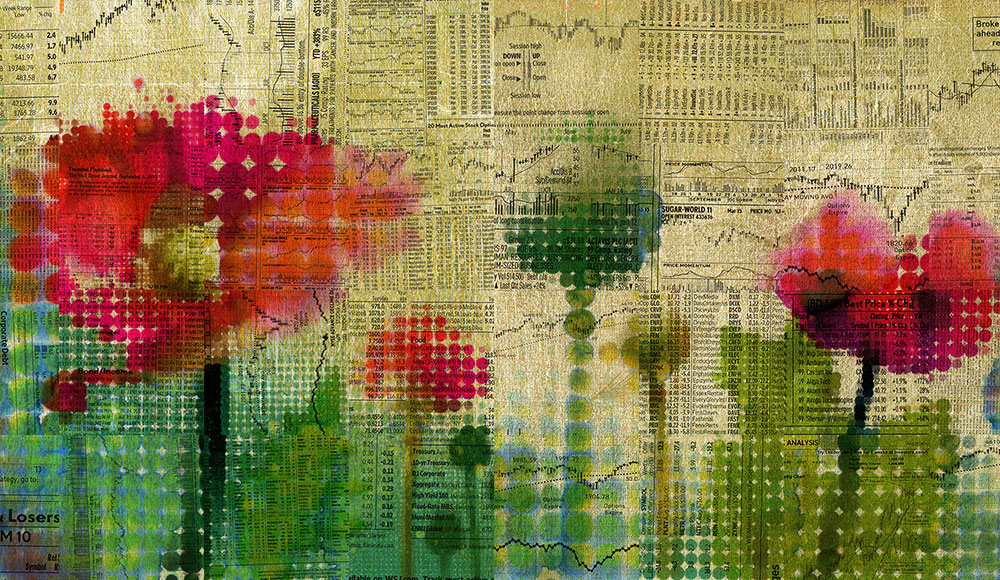

Atlas, like all of the pieces hanging in the gallery, creates an illusion of different ecosystems colliding. The viewer is drawn to the canvas by the central image(s)—a tree, birds in flight, a cricket, flowers or sea creatures.

Hua’s flora and fauna are drawn or painted in lush, aqueous hues. Though he’s of Vietnamese descent, Hua said they’re reminiscent of the Chinese brush paintings he saw hanging in the houses of his family’s friends when he was growing up. “In traditional brush painting, they’re meditating on nature, observing it while they’re painting,” Hua explained.

Hua’s meditations on trees and animals also allude to more urgent, contemporary concerns. His mother’s small farm at the back of the San Jose house he grew up in has since been turned into a housing development. The natural world and the creatures that inhabit it are depicted as totems of a lost world that still exist in the artist’s memory. His use of shapeshifting color patterns—dots and squares cut adrift as they expand into elegant smears and splotches—evoke an Edenic paradise. Whereas the presence of newsprint and packing tape suggests an aggressive age of industrial collisions.

On a trip to China with his father, Hua once witnessed areas of staggering urban growth coupled with smog-filled skies. Where commerce and nature meet, there’s only one guaranteed outcome. “Economic development comes at the cost of the environment,” Hua said. “It was right there in front of me.”

When he returned home, Hua developed a series of environmentally themed abstract landscapes. “I started playing with the idea of a tree on paper because there’s a poetic relationship there, where you’re looking at the image of a tree in its new form—one that we have commodified, cut down and changed.”

Hua’s range of mixed-media canvases, whether as digital monotypes, video installations or on newsprint, are made up of multiple layers that overlap in visual folds. They suggest fields of motion where decay might intrude but the narratives are never static. They keep changing depending upon the way the light catches glints of gold. Or, by the imperfect intersection of angles and corners that communicate competing stories in the foregrounds and backgrounds.

In the digital portrait Past/Future Tense, Hua explained that the layers are different iterations of the same image. “The aesthetic combines different ways that we create and see images,” he said. “I rendered the portrait with different dot sizes until they got progressively bigger, to the point where they almost got abstracted.”

Then Hua will print those iterations, typically five versions, onto rice paper to paint on them, before scanning them back in. “I grid them out, cut them up and place them back in their respective spots,” he said.

While the subject of the world’s disappearing forests, polluted waterways and endangered species lists suggest a mournful exhibit, only one piece stands out as manifestly elegiac. Loss Lullaby holds a giant white cricket in place on a black background. Golden stars and planets light up the night sky above it.

“As a kid, I used to explore creeks and fields, catching bugs,” Hua said. “I would go to bed on a hot summer night and hear crickets.” When he visits his mother in the same house now, decades later, the sound of crickets has faded away. In the intervening years, the region has experienced an economic boom. Office parks and housing have paved over many of those green spaces.

“I am coming home but there’s a sadness there. It’s not what I remember,” Hua said. “A core of inspiration for my work is—What did we lose and what did we gain? And was the trade worth it?”

You Can Never Go Home Again will be on view through January 12, 2025, at the Triton Museum, 1505 Warburton Ave., Santa Clara. Open Tuesday–Sunday, 11am to 4:30pm. tritonmuseum.org