To have Brandon tell it, about the moment that the car skirted off of the main road and onto the beach, making 360-degree stationary turns in the sand, accelerating across the dunes at 100 miles per hour, is to hear a story about far-off destinations and the strange courses one often takes to get there. In no time, the car would be back on a road, this one more abandoned than the last—”There won’t be anyone on this road for miles”—in a forest more ominous than the one before it.

There are understandable qualms regarding the commercialization of almost anything. The biggest fear, perhaps, is the risk of a monopoly. Money, as it tends to, can buy things. A lot of money, as it tends to, can buy a lot of things.

The idea of a commercial enterprise retaining exclusive rights to as large a “product” as the moon is a worrisome one, and is invariably in the back of the average person’s mind when the question of risk arises. Who is to dictate the amount of control these private entities would have if we were to (as we already seem to have) become completely dependent on them?

“There is always the worry about monopolization, and I mean, yes, I worry about that,” Brandon says. “But whether or not I’m that concerned about it right now may be because I’m not there. And to me, right now, it seems like the only way we’re going to get there. So are we willing to risk that happening for the ability to even go in the first place?”

Getting there seems to be just the beginning. Current sideshow and GOP presidential hopeful Newt Gingrich made a speech on Jan. 25 regarding his plans for setting a permanent colony on the moon, even going so far as to frame the moon as a potential future U.S. territory.

His seriousness regarding the plan is of course burdened by context: He announced his intentions in the same breath as his claim to embrace grandiose ideas as a definitive and distinct characteristic of his potential presidency; he also made the announcement in Florida, the state with the largest investment in the future of space exploration—and, conveniently, a major early state on the Republican primary schedule.

For Gingrich, the moon is the logical next step, and could even fall in line with the Northwest Ordinance, which dictates that once 13,000 people reside in a region, it could legally be petitioned as a state. A permanent colony on the moon would allow for just that, and suddenly Hawaii wouldn’t feel so distant.

Of course (and perhaps, as expected), Gingrich, who calls himself a historian, appears to have misstated the number of lunar colonists required for a space-based outpost to apply for statehood: the reality is that the number is 20,000 for self-government in the original bill, which requires the population of the nation’s least populous state—or, now, greater than Wyoming’s 563,626 people (according to the 2010 Census).

“Moon Express is not really associating itself with [the Northwest Ordinance],” says Michael Vergalla, one of the company’s Projects and Aerospace Engineers.

“One of the key things [we’re interested in] is Space Policy, and we plan to use the precedent laws of international waters. If you use your own personal resources to obtain something like oil, fish or minerals, they are yours—but you can’t claim the land as your land.”

The car halts; the driver turns to Brandon, telling him to get out and check the car tire. Brandon refuses point blank, first because his expertise regarding car maintenance is lacking, but eventually because growing tension has made the situation increasingly dangerous—though it would seem not dangerous enough to make the sane decision of getting out. The driver turns to the other passenger, smirks and looks back at Brandon. “I don’t think you understand. This is your stop.”

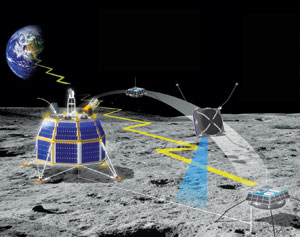

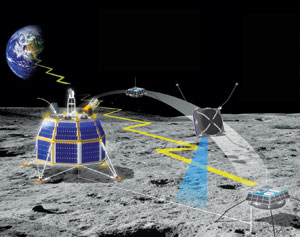

For Moon Express, the Google Lunar X PRIZE is the jumping-off point for a large-scale plan of action that will take the company far beyond the competition’s 2015 deadline.

MoonEx sees the moon not just as a grandiose political statement or a fledgling symbol of faded Americana but also as an untapped resource with the ability to fundamentally drive innovation forward—namely the push for clean energy.

“One of our biggest limitations for having clean energy is that there is only 30 kilograms of helium 3 on Earth,” Vergalla says.

“The moon has a lot of it, and that would be able to facilitate all of this research on clean energy. And suddenly, clean energy pockets start popping up everywhere because the resources have arrived.”

For instance, there is not nearly enough platinum on Earth for the automotive industry to start creating cars that run on fuel cells as opposed to dirty fuel and gasoline, which has been a key facet preventing the clean energy movement from entering the mainstream.

And beyond natural resources, the reality is that the minerals needed to make the dream of a sustainable future a reality are often lost in messy political stalemates and bouts of nationalistic dialogue.

Such was the case just this past year when China blocked Japan off from receiving the country’s export of rare and vital minerals, used in hybrid cars, wind turbines, guided missiles and any advancements made in reusable energy.

Vergalla says that every last mineral we could ever need is available in mass up on the moon, just waiting to be mined.

“There is just no reason to destroy our planet,” he explains. “We can figure out how to go get it elsewhere and have machines do it. We have the technology.”

Bridging the gap between nations is not just a coincidental end result when privatized space travel kicks into high gear, but rather one of the many pros of letting the private sector join the game.

America’s nostalgia-ridden history with the moon—first visited during the height of Vietnam, during a time of outcries from an emerging counterculture and a rampant disillusionment with government—has placed the moon in a curious context. When we arrived, the world seemed, all evidence to the contrary notwithstanding, to have momentarily stopped.

The moon landing became the world’s first global broadcast and brought with it bombastic new patriotism. Yet the mission was prompted largely (if not entirely) by the Soviet-led space race, meaning that while it was “one giant leap for mankind,” it didn’t hurt that it solidified America’s title as a leading superpower, and continued the seemingly endless game of political alpha-dogism.

“The privatization of space travel will liberate the human species from the artificial tribal boundaries that governments are in the business of maintaining,” Richards asserts, settling comfortably back in press release mode.

“Becoming a multiworld species is fundamentally a human undertaking, and any attempts to impose national frontiers off the Earth will not survive long.”

As seemingly “Manifest Destiny”-ish as it sounds for the species, Richards’ view is long-term unification, breaking up the idea of “progress” as a nation-by-nation plan of action. For Richards, it’s all or nothing, and the power of private enterprise and free-market commerce will be the driving force for all major innovation.

“Nationalism is just less important in a private venture,” said Eleanor Crane, Moon Express’ GNC software engineer.

“As a U.S. company, we still have to abide by all the U.S. policies, which control information and technologies that could be used to build weapons systems. This also covers a lot of space technologies, so nationality is still present. But when I think of who we are and how we’ve all been brought together, it’s a shared passion for space exploration that is the most unifying factor.”

If Moon Express has its way, this passion will extend even farther than its lunar scope, working with NASA to reach other planets and, most interestingly, beginning to mine the asteroid belt.

“The belt is literally filled with mineral, water, gold, platinum. You could make rocket fuel,” Vergalla says. “Aluminum, iron. Everything Earth has is there a thousand-times over in the asteroid belt.”

Brandon sees a similar move as inevitable, and considers that the speed may be exponentially faster than we may think.

“What privatization does is it creates a reason to go. It allows not just the incredibly important people to produce things. More people will be able to go because there will be a reason to go and this reason to go will be funding the ability to go É The key is not to be scared.”

The 30 seconds of silence that Brandon describes as some of the scariest of his life were eventually interrupted by a staunch refusal to get out of the car to check the tire, and a tighter hold on his backpack. Eventually, the spell is broken, eyes began blinking, the man in the driver’s seat laughs it off—unconvincingly—and the car starts up again. After a couple more minutes of driving, the passenger suddenly turns to Brandon with a bottle of cologne, spraying it in the car and then aims it directly into Brandon’s eyes. A single instinctual slap of the hand has the bottle flying, and soon the car follows suit, airborne.

There are challenges, as one should expect, in hurling through the sky and getting to the moon.

Vergalla insists that the journey is the least of MoonEx’s concerns.

“Getting to the moon is not as difficult as you may think—it’s landing that’s tricky. You need to know how high you are, you need to be able to look out for rocks, and you need to be able to do that all without someone driving.”

Luckily, NASA has proven quite the passenger, serving as mentors from a distance and aiding Moon Express as it works toward its steadily nearing launch date. Because NASA had a bevy of projects underway before funding was cut and the lunar missions all but permanently cancelled, Moon Express has managed to find use of all the disregarded, half-projects that almost never were.

“[NASA] had a plan to go to the moon, with a lot of projects and satellites to go and support that plan. They’d collected data and everything,” Vergalla says, citing NASA’s leftovers as a great starting point for MoonEx.

“They have a lot of expertise; a lot of good standards,” Vergalla adds. “They’ve been with us for a long time, and they’ll review or comment on what we’re doing, but they won’t give us answers.”

Brandon agrees: “It’s a helpful process, because at the same time Moon Express is learning, and the facilities that NASA has should be utilized.” For example, MoonEx’s partnership with NASA Ames, and aided by the Reimbursable Space Act agreement, has, according to Crane, given the company access to a fantastic test bed that NASA had built: the Hover Test Vehicle (HTV), a prototype lunar lander that has been fitted out with a propulsion system that lets it fly cleanly and safely, using thrusters fed by high-pressure compressed air as opposed to rocket fuel.

Conscious innovations like these lead Robotics System Specialist Krystine Thoroughman to believe that the United States will be at the forefront of commercial and privatized space projects.

“I would like to see America lead the commercial space industry, and in many ways, I think our country needs to pursue these ventures. We need to figure out how to create profitable industries and sustainable jobs. I want to see the country united to achieve these goals today.” She even sees a large-scale project that could help bring about both the industry and the jobs: “America needs to build the railway into space.”

But even though Moon Express is aiming to help bring America back to the forefront of the space industry, it’s the more immediate setting that speaks most loudly about not just where the project is going, but perhaps what it means.

Its headquarters are more than just a place to get started, more than just a setting close to NASA.

Silicon Valley, the starting point of the tech boom, is now helping foster a new lens with which to view a previously government-specific project. And this defining symbol of old America—the moon as a grand statement of hope, possibility and, perhaps, an overly utopian vision of a brighter immediate future—is now being revisited through the parameters of new America.

A new entrepreneurial and individualistically focused generation sees progress as being dependent on the works of the collective, no longer weighed down by vague notions of nationalism, competition and one-upmanship. Here, in the valley, the future involves everyone.

“History will show that Silicon Valley was the springboard for the privatization and industrialization of space necessary for the long-term perpetuation of the species,” Richards foresees.

“This is not an accident. The power and wealth of visionaries who transformed our mainframe world into the personal computing world are now working to transform and democratize the space frontier and open up its infinite wealth and opportunity to change the world.”

Brandon sees it a similar way. “It’s going to have an enormous impact on everybody. Even if there is no gain immediately, the concept of it happening is going to change everything.”

For him, the journey to Moon Express has been so vastly interconnected with a seemingly endless series of events that viewing the possibility of actually succeeding is now simply a matter of faith.

“What do you imagine it changing?” I ask.

“Possibility.”

Brandon starts walking from the gas station the truck that’d pulled the car out of the ditch had taken him to, and it’s at about 4pm when Brandon and his backpack arive at a split in the road. The right path leads to a campsite just three miles down, where Brandon could settle for the night. The left path leads to Camp Reinga, which was still another 40 miles off. Which was still the point at which the Tasman Sea and the Pacific Ocean meet. Which was still the northernmost tip of New Zealand with only two ways of getting there: a bus or something else. As with most things, Brandon chooses the location highest up, farthest away and with the best view.