Sometimes things get blurry. Especially when the columnist violates his scientist friends by stealing terminology from quantum mechanics. Is the observer really ever separate from that which is observed? For example, what happens when the portrait photographer’s voyeurism gets reflected back on him? (And yes, traditionally, more often than not, the one shooting the portrait really was a ‘him.’)

A similar question: In a portrait, what happens when the subject, the sitter, is no longer a passive recipient of the photographer’s gaze and actually provides something besides the stereotypical submissive pose? These types of role reversals are exactly what emerge in Post-Portrait, now on view at the San Jose Museum of Art through January 18, 2015. The show explores eerie aesthetic, psychological, and emotional implications of the gaze in photography today.

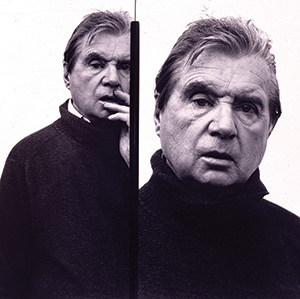

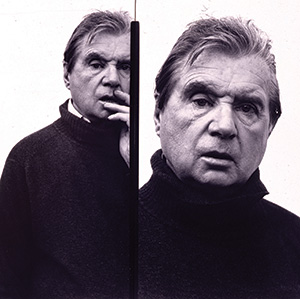

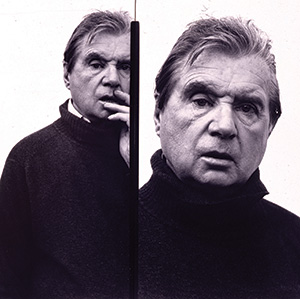

Richard Avedon’s 1979 photo, Francis Bacon (Diptych) presents a dual, gloriously schizoid exchange with the famous figurative painter. Bacon looks at us from two different poses, seemingly cut in half, aghast, or maybe sarcastic. We cannot know. Maybe Bacon’s gaze reacts to the photographer’s gaze, hell bent on mirror-dom as martyrdom. The text panel gives us Avedon’s own words, declaring that in portraiture, the person knows he’s being photographed and what he does with that info is just as important as what he’s wearing or how he looks. “He’s implicated in what’s happening and he has a certain power over the result.”

In another case, the photographer is the subject. Shirin Neshat, from Tehran, Iran, posed for her own portrait, Rebellious Silence (1994), holding a rifle in reference to the Iranian revolution. Afterward she inscribed Farsi poetry on the face of the subject, herself. As a result, the piece blurs the gaze between the observer and the observed, functioning as a ridicule of the stereotypical male gaze toward passive Middle Eastern women.

Suburbia does not escape ridicule either. Beth Yarnelle Edwards presents a staged photo, circa 2000, titled, John, from her series, “Suburban Dreams.” It looks like a film-still from a Silicon Valley suburban dream (or nightmare), with the dad leaving home for the workday, armed with a 1990s-era cell phone, coffee mug and pager, plus a generic blue dress shirt and khaki slacks. Meanwhile, his daughter follows behind, clad in a private school uniform, while mom stands further back, looking on from the staircase. One can’t tell if the family is posing or if this really is their generic suburban life.

The show also includes more experimental or nontraditional approaches. Jim Campbell, who lives and works in San Francisco, presents two photographs of his parents, underneath glass and plastic, which appear and disappear when triggered by recordings of his own heart beating and his own breath. As the heart beats, as the breath inhales and exhales, the photos emerge from behind the glass, only to disintegrate all over again. Thus, Campbell uses physiological aspects of his own body to animate memories of his parents.

In another case, San Jose’s Binh Danh, an SJSU graduate originally from Vietnam, creates images on plant leaves. Danh’s work has emerged in shows all over this area, and sometimes the work is eerie to look at, especially in this case. When sifting through archives held by the Khmer Rouge, Danh discovered some haunting photographs of prisoners, in which the subjects stare defiantly at the camera. Danh then collaged the images with butterflies in order to symbolize rebirth and release from the past.

Additional images include a hysterical triptych from Elizabeth Heyert’s series, The Narcissists, in which she photographed her subjects by placing each of them alone in front of a one-way mirror, allowing them to gaze at themselves and momentarily become who they want to become. We see a subject, Mark, a man with a long beard, apparently standing in front of a dressing-room mirror, trying on a gaudy fur coat. As the photographer, Heyert becomes a secret voyeur, an invisible witness to the supposedly private moments of her subjects.

What’s more, the gallery viewer adds yet another layer to the experiment. As he or she traipses through the space, another element of voyeurism emerges. As we view the photographer’s gaze and the subject’s return gaze, which in this show is a hall of mirrors already, does our very presence affect the experiment? I will leave the answer to the quantum physicists.