A grainy untitled photograph by Marcy Stoeven depicts an abandoned apartment. Broken glass, a destroyed fridge and scattered plaster comprise the subject matter. In the text panel, Stoeven writes that her PTSD came from domestic violence, resulting in a sense of isolation.

She often can’t get out of bed or pay attention to anyone’s stories. She wants to connect, but doesn’t know how. “I’m a photographer and often take pictures of abandoned buildings, maybe as a metaphor for my sense of isolation.”

Stoeven’s photo is only one of several artworks, all part of PTSD Nation: Art and Poetry From War, Gun Violence and Domestic Abuse, currently occupying the Jennifer & Philip DiNapoli Gallery on the second floor of the MLK Main Library until April 28. Through dozens of visual works, writings and stories, the exhibit rams it home that PTSD is not even remotely limited to those with military combat experience.

The exhibit unfolds in five different sections, accompanied by numerous hanging scrolls with explanatory information. “Our Harming Traumas: How PTSD Found Us” depicts the condition as a room, common in America, although many come into that room through different shaky doors. For example, one can grow up in a dysfunctional household, witnessing domestic violence or emotional abuse for years and then develop PTSD. Having relatives or friends die from gun violence, anywhere, can also result in similar symptoms. Everyone trembles and bleeds equally. Whether the triggered traumas are physical or psychological, all survivors share an element of recurring terror, in that they simply don’t feel safe.

That’s just the first section. The next scroll, “Our Brains (And Lives) On PTSD,” explains in common language the mechanisms of the brain and nervous system, and how they’re different in people with PTSD. Another section, “What Impedes Our Healing: Triggers and Retraumatizations,” will be especially revealing for many. Aside from incidents triggering feelings of trauma, survivors might also experience retraumatizations, which are different. In such cases, your brain is practically rewired into its most limited capacity to protect itself against perceived danger. Seemingly minor inconveniences or frustrations—things non-PTSD people would claim are just part of everyday life—might have dramatic effects on people already emotionally raw with PTSD, people who already exhibit vulnerability, a lack of ego strength or limited personal power. These retraumas can be devastating, adding new dimensions of not feeling safe.

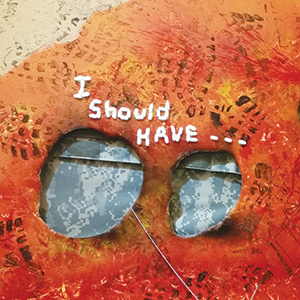

In a mixed media work, “I Should Have …” by Julia Marshall, different layers of the work represent different layers of healing. Marshall, a combat veteran, explains in the accompanying text panel that after a military friend of hers committed suicide, the empathy she felt for him was balanced by the rage she felt toward a system that left both of them broken and alone. For those with PTSD, just viewing violence in daily life, being treated abusively, or seeing others being treated abusively, can often trigger conditions that further impede healing.

Which brings us to the last few sections of the show: “Healing: The Power of Kindness and Other Modalities” features even more visual artworks, poetry and explanatory information. Some of the artists explain how the creative process was part of their self-therapeutic journey. At the end of the exhibit, tips for survivors, loved ones and communities are listed on more hanging scrolls. For individuals with PTSD: learn everything you can about the condition and be your own gentle monitor of your symptoms. Keep telling your story. Tell it to a journal if no one safe is available. For the public: consistently treat each person with tender kindness and dignity. For society: establish free PTSD support groups in every community.

No matter how much the viewer might think he or she knows this material, something in the exhibit will hit close to home, and maybe even manifest new degrees of empathy. The final section leaves the viewer with a distinct sense of hope. “A Wall of Heroes: Healing, Capable, and Deserving of Praise” presents a grid of 32 examples of people with PTSD who’ve gone on to become artists, writers, educators, counselors and many other professions, all talking about how they’ve dealt with the condition.

PTSD Nation: Art and Poetry From War, Gun Violence and Domestic Abuse

Free

DiNapoli Gallery – MLK Main Library

Through April 28.