On the property of Montalvo Arts Center, sequestered in the redwoods above Saratoga, a narrow road curls around Parking Lot 1 to reveal 10 LEED-certified, discipline-specific art studios built into a forested hillside along a few miles of hiking trails. It is here, in these studios, that hundreds of artists, local and global, have temporarily lived and created since the Sally and Don Lucas Artists Residency Program was launched in 2004. The program will celebrate its 20th anniversary with a grand-scale party at Montalvo on May 4.

In one form or another, artist residency programs began at Montalvo in 1939, which makes the whole program officially the third oldest of its kind in the United States. However, by 2004, major upgrades brought the program into the modern world. Architects were hired to design brand-new studios along with a commons building. Each studio is an architectural marvel in itself, created specifically for visual artists, composers, literary scribes, sculptors or the creation of performance works.

Among many other projects, Montalvo is also creatively addressing the nativist and racist politics of its founder, California Senator James Phelan, whose virulent opposition to Chinese and Japanese immigrants, and his active endorsement of multiple Asian exclusion acts have been whitewashed by frumpy San Jose historians for too many decades. “Keep California White” was one of Phelan’s campaign slogans during his failed 1920 re-election bid, for example.

To counterbalance Phelan’s unfortunate legacy, Montalvo is copresenting an exhibit, P L A C E : Reckonings by Asian American Artists, at the Institute of Contemporary Art San Jose (ICA San Jose). All participating artists in the show are alumni of the Lucas Artists Program.

P L A C E is not about Phelan per se—he’s briefly mentioned at the beginning—but instead centers on the voices of Asian diasporic artists who have had to put up with this racist history while in residence at Montalvo. The title P L A C E contains extra spaces for this reason—to suggest not just a single place, but all the spaces, in and between, that influenced the artists’ lives and creative work.

ON THE WALLS

At the P L A C E opening reception, professors, punks and politicians are standing side by side. Trustees, donors, boards of directors and reporters listen to speeches from curators and longtime directors of both ICA San Jose and Montalvo.

In the gallery, the microphone is passed around between the organizers. Saratoga mayor Yan Zhao hands letters of recognition to P L A C E curators, Zoë Latzer and Judy Koong Dennis, as well as Lucas Arts Residency Director Kelly Sicat. As the VIP and members-only preview fades into the public reception, about 100 people remain in the gallery, while dozens more continue to flow inward from the sidewalk. In my memory, I have never seen ICA San Jose crammed with a more colorful variety of people.

P L A C E features nine California-based artists and three collectives, with each artist exploring the ill effects of xenophobia, anti-Asian American hate crimes, the erasure of Asian immigrants from California history, migration in general, or even problems with the very term Asian American. Too many confused folks still treat “Asians” as some kind of monolith, so the text panels often present the artists’ own words.

“Both for our curatorial and my own curatorial sense, that’s why we really wanted the labels to be in the artists’ voices, and the kind of narratives be really individualized to those artists’ perspectives, versus having a theme that summarizes everyone’s practice,” co-curator Latzer says.

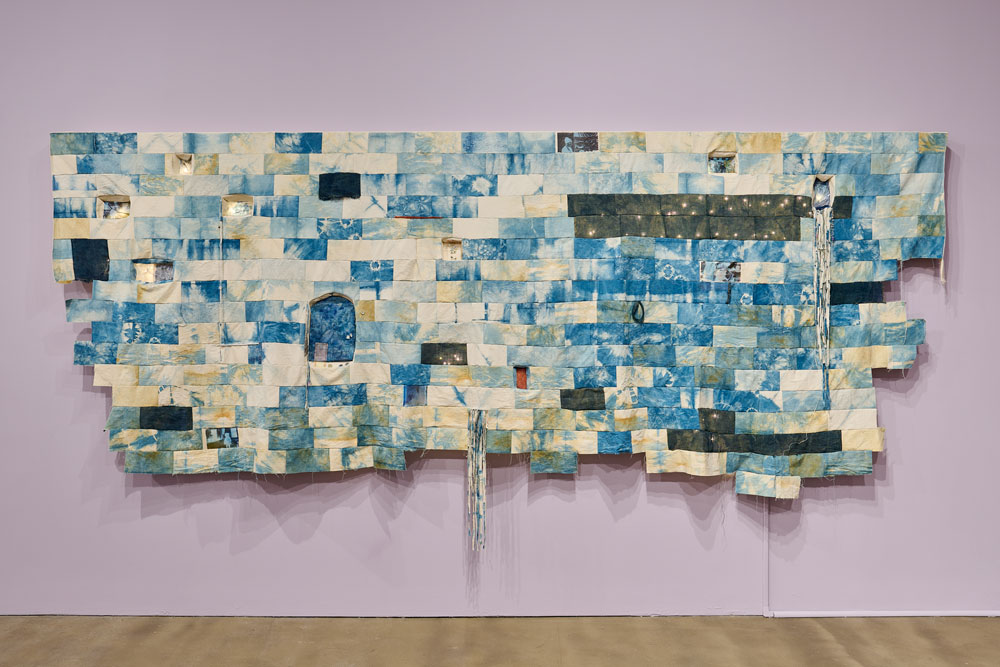

At the opening, I make a beeline for Namita Paul’s work, W.M. 265. A huge canvas and burlap wall-hanging with additional components of indigo dye, sequins and acrylics, the work draws from personal and political histories, engaging with themes of home, rupture, repair, architectural space, memory and time. W.M. 265 was triggered by artifacts and memories of Paul’s childhood home in Jalandhar, India, a building where her grandparents lived after being displaced by the Partition of India.

“I was born in that house, it was a home birth, and that was the house that my grandparents had moved to after Partition,” Paul explains. “They had just built their house in what is now Pakistan, and they had a booming business, and they left all of that. And to date, I cannot comprehend the kind of trauma they went through.”

SITE SPECIFICS

Each artist awarded a residency at Montalvo has free rein of how they use their allotted time. Montalvo gives them a total of three months, but those three months can be used over the course of three years. So an artist can use the time all in one chunk, three straight months, or they can break up the time into two-week segments, six times over.

“The course of three years is a very different kind of model,” Sicat elaborates. “It’s not an easy model to administer. However, for an artist, it makes a lot of sense because it allows them to build a body of work over time. It also builds a relationship with the place. And that, I think, is deeply important for Montalvo and for the residency because we’ll often invite artists to come back and do a performance, to come back and show their work, maybe on the grounds, or come back and do a collaboration such as we did with the ICA.”

Among the most fruitful highlights of any time spent at the Lucas Artists Residency Program, according to what several artists have told me over the years, are the community meals. Catered lunches and dinners unfold in the commons building. Inside the building, a full professional kitchen sits just off a central room, where a long epicurean table accommodates approximately 18 people.

Through huge glass doors, one can view the fire pit outside, backdropped by the verdant forested landscape, as the road snakes up toward the artist studio structures.

For the meals, any artists currently in residence who want to come down the hill from their studios may then break bread and wine with whomever else is present. Choreographers, composers, sculptors and writers—or often people who are more than one of those—swap ideas and philosophy, or simply just talk shop about the creative process.

“The highlight of the program for me, the first two weeks, were the artist conversations that we had with the dinners,” Paul says. “It is amazing to have visual artists, composers, writers, curators, everybody at the table, and you talk about process, and you talk. It’s just fascinating. I think that was so enriching.”

Paul’s words echo those of writer Jeff Chang, speaking to me at the P L A C E opening reception. The first thing he mentions is the dinner conversation at Montalvo, having just completed his Lucas residency.

Sicat concurs: “The table is the glue,” she says, adding that the table might even be how Montalvo determines who comes into the residency, and how they diversify who comes into the space. “It’s thinking about really who’s coming to dinner and what’s the makeup of who’s around the table,” she says. “You’ve got composers and writers and visual artists and performers, but you get to have people coming from Asia, coming from the Middle East, coming from Europe, coming from Lodi, coming from LA, coming from San Francisco or Santa Clara County.”

FOOD FOR THOUGHTS

A few weeks after P L A C E opened at ICA San Jose, I joined the current Montalvo resident artists for dinner, where Chef Jose Ortiz, also of the Bywater restaurant in Los Gatos, was preparing the meal. Seemingly moments later, there we were around the table, as Ortiz brought out seasoned chicken, green beans and au gratin potatoes, along with a medley of grapes and blackberries, but not before a simple salad of greens, red onions and fresh tomatoes.

At the table, Sicat wore a button with the words “IT IS POSSIBLE”—the button being a work by the late Susan O’Malley, one of the most uplifting people ever to emerge from the San Jose art scene before she passed away nine years ago at the age of 38. O’Malley was a curator at ICA San Jose and her memorial took place at Montalvo. The two institutions seem forever connected.

The artists around the table seemed to follow the sentiments of O’Malley’s button, refusing to restrict their own work to traditional academic disciplines. Leah Rosenberg, from San Francisco via Ann Arbor, endeavors to blur the boundaries of visual art, sculpture and cake making. The genre-shattering Stella Zhang, originally from Beijing but now guest lecturing at Stanford, has produced all sorts of objects and visual presentations over a long international career. Avant-garde composer Fernando Vigueras, a notable contemporary music scenester in Mexico in residence at Montalvo while teaching at Stanford, works on experimental sound practices and creative guitar re-imaginings.

Sicat then passed around an advance copy of the Montalvo book Hello, Goodbye, Hello, a publication documenting the role played by the Lucas Artists Program in the lives of the 1,600 artists who resided here over the past 20 years. Filled with stories, retrospective essays, poetry and other texts, the full-color book will be given to VIP ticket-holders at the 20th anniversary celebration on May 4.

Everyone at the table seemed stoked for the anniversary. Back and forth, we shared dinner, donuts and stories. It was a little quieter than previous Montalvo artist dinners I’ve attended, but the serenity was inspiring. Montalvo is both an artistic and spiritual nexus, a conjunctive meeting point, the muse as a connection machine, bringing everyone together over a shared meal.

PLACE AND TIME

P L A C E unfolds in three sections. Some artists examine the physical, mental and emotional toll of migrating or emigrating to a new country, while considering what it means to be an “American.” Others address the sources of racial violence, responding to racial discrimination and transgressions against Asian American communities or the exploitation of Asian American labor. The exhibition concludes in the back room with Christine Wong Yap’s community engagement project displaying stories of belonging she collected in various parts of the Bay Area.

Ultimately, the show expands on many now-familiar yet controversial arguments. Should we allow people to smash all the statues of racist figures throughout history? Do we change the street names and thus remove the history altogether? Or, to use another local example, do we leave the Fallon statue intact with the vandalism also intact, as a depiction of the resistance to these characters throughout time? Why not instead give artists a voice?

“People have been like, well, why are you still talking about Phelan?” Latzer said. “Get rid of his name. Just take it off. Take off his name, erase, decenter his voice, erase the whole history.”

This was not the point, she said. The curators worked hard to mention Phelan’s legacy, but without making it all about him. The show endeavors to give artists their own spaces.

“What I think we try to do is show the layer of history, not to only focus on Phelan and that history, but to also show how thought and time have progressed, and where we currently are, and that these issues are still persisting,” Latzer said.

Anti-Asian violence didn’t just suddenly come out of nowhere, nor did the resistance to it.

“There’s been a lot of change and thought as well, and people reckoning,” she added. “And I think the key word there is really ‘reckoning’—with this history, and moving forward too.”

P L A C E: Reckonings by Asian American Artists runs through Aug. 11 at the ICA San Jose, 560 S First St, San Jose. The exhibit features nine artists—Christy Chan, Phung Huynh, Ranu Mukherjee, Namita Paul, Valerie Soe, Stephanie Syjuco, Christine Wong Yap, Bruce Yonemoto and Wanxin Zhang—and three artist collectives: Mail Order Brides/M.O.B. (Eliza O. Barrios, Reanne Estrada, Jenifer K. Wofford), Related Tactics (Michele Carlson, Weston Teruya, Nate Watson) and Adrienne Pao and Robin Lasser.

Great read, Gary