An hour and a half into KFJC’s weekly all-staff meeting, a voice rises from the back of the auditorium.

“This album is an exploration of krautrock, ambient soundscapes, house music and noise,” Dangerous Dan announces. “A patchwork of various genres woven together.

This is an awesome album, and I’m predicting it’s going to get a lot of airplay.”

Up at the front of the room, an overhead projector casts the album artwork onto an enormous screen. The cover is red, spare and confusingly labeled. After some parsing, you can kind of make out the band name: Eye O.

If you’ve never heard of Eye O before, you’re not alone. The experimental San Francisco duo only has about 400 “likes” on Facebook. On YouTube, their most viewed video is in the double digits. Yet, at KFJC they’ve found their ideal audience: a dedicated collective of music lovers, determined to chart the absolute outer edges of sound.

Over the next hour, the gathered crowd listens, some taking detailed notes, as the station’s music department delivers live album reviews of their weekly acquisitions. There’s Egyptian bellydance music, San Jose hardcore, Japanese noise and one record of unaccompanied saxophone that DJ Goodwrench describes as sounding “like either a grumpy elephant or someone squeaking a wet balloon.” Overall, it is a positive review.

As of this past weekend, KFJC has been broadcasting at 89.7 FM from Foothill College continuously for 60 years. In a tradition that stretches back to the mid-’70s, every Wednesday the staff gathers in room 5015 to discuss the ongoing health and sound of the station. In addition to Dangerous Dan and Goodwrench, a handful of other DJs are in attendance, including Cousin Mary, Medusa of Troy, Number 6, Grawer and Cynthia Lombard. All of them have devoted countless hours and years of their lives to the station.

In the age of streaming media, college radio may seem hopelessly quaint, an anachronism held over from a bygone era. But at KFJC, there is an undeniable sense that something vital is happening. Instead of trying to compete with services like Spotify and Pandora, KFJC has instead made itself the home of music’s last true outsiders, those rebels, dreamers, and experimenters whose work remains largely invisible to the algorithm.

Poised at the bleeding edge of the underground, and populated by people who care passionately about music (and very little about anything else), it is one of the most unlikely successes in Bay Area historythe “Wave of the West.”

HIGHWAY 280 REVISITED

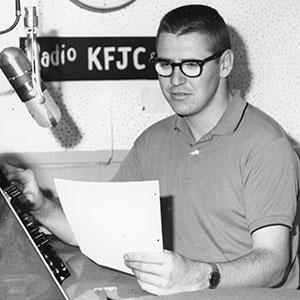

The idea for a radio station at Foothill College can be traced back to one person: Bob Ballou.

“The community had just approved a $10 million bond to build the new campus, and it just seemed right that it should have a radio station,” Ballou says in a taped interview from 2009.

Ballou was a student of Foothill’s first class in 1958. At the time, FM radio was still a novelty, but a teenage Ballou and a classmate approached the school board with an idea for a student-run FM station, the board unanimously approved the idea. On Oct 20, 1959, KFJC hit local airwaves.

In its earliest days, the station broadcast from a broom closet. Its 10-watt transmitter was roughly the same strength as a hand-crank generator. A schedule published in the second issue of the Foothill News lists its debut programming as including an hour and a half of “study music,” followed by an “audio show.” At 10pm, the signal went dark.

The station set up a permanent base in 1961, when Foothill relocated to its current campus in the Los Altos Hills. No longer broadcasting out of a closet, the new station had three studios and a control room and functioned as part of the college’s Mass Communications Department. That November, the Mercury News published a quote from then-station manager Vic Blondi, who said that only non-offensive, “middle-of-the-road-type music will be presented”far from the “wet balloons” and Japanese noise of last week’s additions.

Still, from its very inception KFJC had a roguish streak. In 1962, the station again made headlines, this time for its DIY spirit.

“A discarded crutch is being used to carry broadcasts from Foothill College’s FM station KFJC,” the article in the Mercury begins. The fix had been rigged up by Douglas Gardner, the station’s 26-year-old engineer, after the previous antenna had become corroded. “The crutch was just the thing. It was varnished and waterproof, and it was adjustable for tuning,” he boasted to the paper.

He continued with a little good old fashioned trash talk.

“I don’t know who made the other antenna, but he obviously didn’t consult anyone in the engineering department,” Gardner said. “The size and design are good, but the material is quite inferior.”

AMALGAMATED WARLOCKS

Doc was born in LA. “A good place to be from,” as he puts it.

Since 1980, Doc has been KFJC’s station supervisor. Like many at the station, radio was a big part of his youth. In high school, he tuned in to KCRW out of Santa Monica College, 89.9 on the FM dial. It was there that he found a refreshing freedom in the station’s non-commercial format.

“They had a folk guy, a jazz guy and a rock guy,” Doc recalls. “They’d come in when they got off from whatever they’d been doing, and they’d play music until they got tireda lot of music you’d never heard before.”

Just as important: “There were no ads and no jingles.”

When he began looking at colleges, Doc knew wherever he went had to have a radio station. In the spring of 1968, he ended up at UC Berkeley, home of KALX.

“Literally the day after I arrived, I went to find the station,” he says.

Doc’s show was called the “the Amalgamated Warlocks and Vampires Tuesday Afternoon Chewing and Sucking Friendship Club.” Predisposed toward rebellion, he says he chose the name to annoy the guy who made the program guides.

“He was making up the schedule and had these little boxes. So I gave him a show name that he couldn’t cram into the box.”

Over the following decade, Doc would spend eight years as music director at KALX, a position whose initials (M.D.) led to his enduring nickname.

While Doc was working at KALX, up in the Los Altos Hills, KFJC was going through some major changes.

Throughout the ’60s, the station received grants for educational programs, which it invested in updating its equipment. Then, in 1966, there was a brief scare after District President Calvin Flint (of Flint Center fame) declared radio a waste of school funds and tried to shut the station down. That June, for the only time in its history, KFJC went dark. The following October, it returned to the air with renewed community support, as evidenced by a Mercury article headlined “Foothill FM Fans Loyal.”

The following decade, KFJC raised its profile significantly, taking on a more professional style and presenting a number of major concerts on the Foothill campus. There was rock guitarist Tommy Bolin and Jose Feliciano, the Puerto Rican musician who recorded a hit “Light My Fire” cover and wrote “Feliz Navidad.” In 1977, in a co-production with KSJO, KFJC hosted Journey on campus. Perennially ahead of the curve, it would be just one year before the already-established band released “Wheel in the Sky,” the massive hit that launched them toward their ultimate status as a karaoke bar staple.

Then came the mutiny of 1978.

That October, in a rare show of internal discord, a group of managers voted out KFJC’s presiding general manager, arguing that his style was too rigidand even worse, that it was too mainstream.

“This was a defining moment in KFJC history,” the station wrote via a recent Instagram post. “The mutineers take control of KFJC, waving high the banner of punk.”

Shortly after the insurrection, the position of radio station supervisor and broadcasting instructor opened up at Foothill. It was a dual-purpose role. Whoever stepped in would oversee day-to-day operations at KFJC, as well as teach the academic courses for the school’s major in broadcasting. More importantly, whoever filled the role would be the liaison between the station and the school’s administration.

By this time, Doc had spent two years as general manager at KALX, and had seen just about every angle of the college radio game. When a friend told him about the position at Foothill, he applied, going up against candidates with PhDs and commercial radio experience. Somehow, the host of “Amalgamated Warlocks” got the job. In 1980, Doc left KALX and joined the staff at KFJC.

Cut from the same cloth as the mutinous DJs who had ousted their former manager, he fit right in.

INFINITE LOUIE

It was in this environment that the station staged what is without a doubt its most transcendent stunt: Maximum “Louie Louie.”

Beginning at 6pm on Friday, Aug. 19, 1983, KFJC broadcast, for all to hear, every last version of “Louie Louie” that its DJs could get their hands on. The most popular version of the song, recorded by The Kingmen in 1963, lasts 2 minutes and 44 seconds. When the marathon was first announced, Maximum “Louie Louie” was expected to run for 30 hours. By the time it ended the following Monday morning, it had run for more than 63. Even then, there were still versions left to play.

“When it started, we had no idea how long it was going to go,” Doc says. “The station manager at the time finally realized that versions were coming in faster than we could play them. We had to have a cutoff point, otherwise we’d probably still be doing it.”

In total, KFJC aired more than 800 consecutive versions of “Louie Louie” that weekend. There were classical versions and dub versions, versions sung in the style of Bob Dylan, and versions recorded in nearby garages along the Peninsula. There was also a special performance: “Louie Louie” performed live in studio by the song’s original writer, Richard Berry. Joining him on the song were Lady Bo (Bo Diddley’s rhythm guitarist and one of the greatest guitar players of all time), and the man who popularized the song: Jack Ely, vocalist for The Kingsmen. Their version of the song lasted 45 minutes.

Maximum “Louie Louie” attracted the attention of national news outlets. Inspired by the marathon, Rhino Records released a “Louie Louie” double-album compilation, for which Doc wrote the liner notes.

However, Maximum “Louie Louie” also had an unexpected effect on the life of the song’s original writer.

In 1959, Richard Berry was just 24, a poor artist trying to get enough money together to marry his sweetheart. With plans to pay for a wedding, Berry drew up a contract on the back of a napkin and sold the rights to “Louie Louie” for $750. Four years later, The Kingsmen version of the song was a worldwide hit.

About 30 hours into Maximum “Louie Louie,” Berry got a call from an artists’ rights firm. Having heard about the marathon, they wanted to help him get the rights to the song back. Their bid was eventually successful.

There is a sincere pride in Doc’s voice as he describes this correction to history.

“It’s like the reverse of the normal story of white people exploiting the black artist and making all the money off of them,” he says. “He still didn’t make as much money as he should have, but at least he was able to end his life by reuniting with his family, playing music with his son and driving a Cadillac.”

NEW FRONTIERS

Before he joined the station in 1991, Grawer was a skater from Cupertino with a passion for recording equipment.

“I was always nerding out on four-track cassette recorders, mixing, all that,” he says. “When I came to the station, there wasn’t a whole lot of equipment, but they had reel-to-reel players, so I learned how to do that.”

Like KEXP in Seattle, and Tiny Desk at NPR, KFJC had long been recording touring bands when they came through town. But by 1994, the station had become more ambitious. That year, the station sent a crew to South by Southwest in Austinthen still an up-and-coming festivaland broadcast the events live on air via satellite.

At the time, it was noteworthy technical achievement for such a small station. Thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment had to be purchased and shipped. A relay point was set up in a nearby hotel lobby. In a first for college radio, 30 different stations around the country ended up picking up the broadcast, effectively distributing KFJC’s programming countrywide.

Two years later, Grawer and a crew traveled to Brixton, England to record another festival, their first international trip. Not long after that, they went to New Zealand for the Otago Arts Festival, where the station captured one-of-a-kind live recordings of some true legends of the Kiwi undergroundartists like The Verlaines, The Dead C and Alastair Galbraith, whose influence shaped the sound of alternative rock in the ’80s and ’90s.

“We’ve built a pretty good crew of folks who are kinda rugged now,” Grawer says. “People who can pack light, go over, do a couple of live broadcasts from somewhere, then head back.”

Around the same time, Maybelline had come to the Bay Area for a job. An enduring fan of the magic of live music, Maybelline had moved to the Bay Area in the hope of landing in San Francisco. Instead, she found herself in Foster City.

“It was so boring,” she says. “I don’t know how I found out about KFJC, but it saved my life.”

After listening for a few years, she became a DJ in 1998, picking up a slot on Friday nights. For the last 21 years, her show, “Girl Version,” has made an effort to champion women on the musical fringes.

“I go through a lot of different genres, but to me it’s kind of like a big art project or something. A big collage, maybe.”

In 2014, Maybelline found her way onto Grawer’s international crew, interviewing bands between live performances at the festivals.

“The first festival I did with them was the Liverpool Festival of Psych,” she says. “It was just amazing. The fact that we do that, and no other station does, it’s incredible.”

Since then, she has been behind the mic at festivals in Iceland and Germany, where she has beamed some of the strangest music happening anywhere in the world directly back to the KFJC studios and the Bay Area at large.

Maybelline’s most important contribution to the station, however, was something much closer to home.

A major part of KFJC is its yearly fundraiser. Primarily volunteer-run, the station relies heavily on listener donations for its survival. Every year as part of the promotion, the station has new shirts and merch items designed for listeners.

But by 2001, Maybelline, then the station’s promotions director, noticed something missing in the merch.

“I was so tired of wearing guy’s shirts,” she says. “Women want to wear cool shirts, too.”

It’s still a problem to this day. Band shirts often still come online in male sizes. Up until Maybelline registered her complaint, the same had been true at KFJC. Already a champion for gender equality on air, she took to correcting the gender gap in the station’s merch.

That year she commissioned the station’s first shirt for women, designed by Niagara, frontwoman of the legendary underground Detroit group, Destroy All Monsters. In one act, she made the station more accessible to women listeners and helped increase the profile of one of the most important women musicians in America’s underground.

“The girlie shirt has been extremely popular ever since,” she says.

ON AIR

Today, there are only three paying jobs at KFJC. But that doesn’t seem to bother the 30-odd people gathered in room 5015 for the weekly all-staff meeting. By the time the gathering adjourns at 9:30pm, some have been discussing the station’s goings-on for almost four hours.

“I’m always blown away by the passion that people have for the station,” says publicity director Cynthia Lombard, host of the Tuesday evening show “Too Cool For School.”

“But,” she continues, “I think that’s the appeal: being around a bunch of like-minded people who are so deeply interested in music.”

Like Doc, Grawer and Maybelline, Lombard is a lifera believer. This year marks her 20th on the air at KFJC.

She appreciates “the fact that it’s not commodified, maybe. The work that we put into it is truly for the love of the station. I think there’s something kind of special about that.”

While the rest of the industry closes in on independent broadcasters and radio conglomerates such as ClearChannel and iHeartRadio continue to homogenize the country’s airwaves, KFJC shows no signs of selling out or slowing down. Now, two weeks into their annual fundraiser, they’re right on track for another successful year.

It’s cause for Doc to ruminate on the state of music.

“Sometimes you’ve got to stop at McDonald’s because it’s quick, and you’re in a hurry,” he says, standing in the KFJC lobby. “Other times, you want something more experimental, something that’s unique and different, and not mass produced.”

As he speaks, the relative quiet in the room is suddenly punctured by a frantic drum fill exploding from the lobby speakers, followed by the sprightly swell of what I can only call “Hawaiian honky-tonk.”

Doc continues, unphased.

“We like to think that there will always be an audience for that.”

This article is dedicated to the memory DJ Buddy Love and his surviving family.