The latin phrase “deus ex machina” describes a theatrical device in which an actor in the role of God appears on stage to neatly wrap things up. It’s artistically primitive, but it still exists in evangelist Christian films. Alex Garland’s science fiction film Ex Machina—a masterpiece if ever I’ve seen one—seemingly clips the God from the equation in depicting a bad demiurge of a high-tech tycoon.

Nathan (Oscar Isaac) is the founder of Bluebook, named in honor of Wittgenstein’s privately circulated journals on human consciousness. This search engine, with its 94% market share, has left Google, Baidu and all the rest in the dust. At the beginning, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), a Bluebook employee, seems to be the luckiest young man in the world. He has won the ultimate golden ticket—a week in the company of the genius who created Bluebook’s algorithms when he was just 13 years old.

This story would only work if we could believe in a real life Dr. Frankenstein or a Dr. Moreau, and fortunately Ex Machina delivers such perfect plausibility. Nathan’s headquarters make you believe it, not out of their Olympian splendor, but out of their sparseness. The genius lives in a compound that takes hours to fly over, in what seems like an eco-friendly recycled boxcar built over a mountain stream. This cyber-lord is attractively brutish, muscled and bearded with a close cropped head. He hits the bottle as hard as he hits the punching bag.

Isaacs kicks himself right up to the top with this performance. Embodying everything you’ve ever loathed about the Valley’s titans. Nathan has a New York accent, but he also has that false, antic friendliness we Californians use to hustle people from the Eastern Seaboard. He has the fetish of crypto-Asianess—his cottage is meant to be as austere as zen itself. In fact, it looks like what it is, a concrete bunker. Nathan has that mania for control, that resounding, untroubled, unforgivable sexism. He has the patronizing assumption of homo-superior status on the simple grounds that he knows how to click a keyboard the right way. And he has that greedy crawly paranoia barely masked as coolness. One arm embraces in a half-abrazo as the other arm hands over an iron-clad confidentiality agreement.

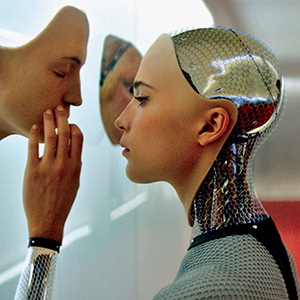

Far away from the world, Nathan is hiding his insanely great development: artificial intelligence in a human frame. The intelligence is called Ava (Alicia Vikander) and she is as beautiful as she is strange. She’s the most chilling non-human I’ve seen since video artist Elizabeth King’s creation, “Pupil,” animated in the ahead-of-its-time 1991 clip “What Happened.” Ava is like that old biology lesson in toy form—the Visible Woman—come to life. She has glass limbs; you can barely hear the soft soughing of rotors as she moves. Vikander was apparently a ballerina once, and her movements have just enough stiffness to be unnatural. She has a sweet, plaintive face—a captive’s face. She’s eager to please. Playing dress-up in dowdy clothes; she teases Caleb by telling him not to look as she covers herself. Mutely, she beseeches for freedom.

Images of robot human love go back to Jean Marsh’s lovely android in the Twilight Zone episode “The Lonely” (1959) and likely beyond. Working simply and lucidly, director Alex Garland transcended the tragic-mulatto side of such stories. He’s put teeth and chill into what has either been an empty sci-fi threat, or else has been sentimentalized to death, as in the very bad Chappie.

Ex Machina has its fairy tale element. Nathan decorates a hallway with masks, some grotesque, one ultra-realistic. It’s like the human arm torchiers in Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast. And there’s certainly an element of Bluebeard’s castle in this tale. I’ve read the counter critiques—one critic called this story misogynist, when the point is that Ava isn’t a woman. We know why Frankenstein rampages: he’s alone and hurt and badly treated. Ex Machina hits you: is there a right way to treat such a creature? Would kindness even matter?

R; 110 min.