When I interviewed horror legend George A. Romero several years ago, he had recently been sent a script about the life of Edgar Allan Poe. He had been interested in directing it, and in an attempt to get across to me how Hollywood works—or more accurately, doesn’t work—he explained why he didn’t get the job.

“They said, ‘Well, we think it needs a little rewrite, but we’d love for you to do it. We think you’d be good for it, blah blah,’” Romero told me. “Every fact in it, about dates and where he lived and everything, it was just completely wrong. I knew a lot of that, and I said, ‘Oh boy, I’ve got this gig sewn up.’ So I called back and pointed a lot of these things out, and they said, ‘Oh, we know that. It’s just not the way we want to go.’”

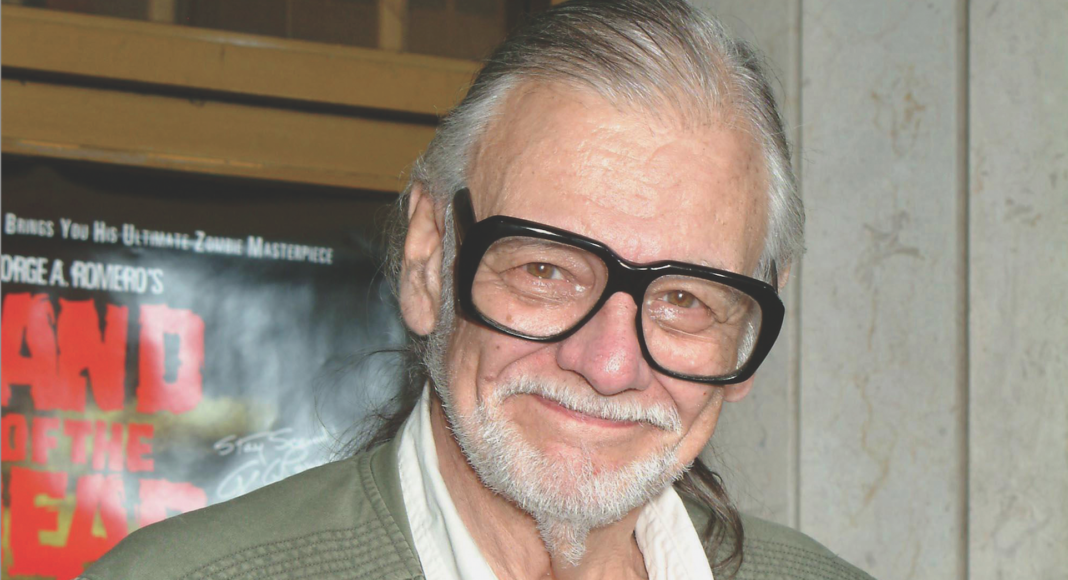

His sheer head-shaking disbelief at the way that deal didn’t go down was Romero through and through. When he died Sunday at the age of 77, the horror genre lost not only an iconic writer and director, but also a man who had served as its moral compass for almost five decades. He had integrity, smarts, loyalty and a strict ethical code. He was an indie filmmaker before indie filmmaking existed, and stuck to making most of his movies in his longtime adopted city of Pittsburgh (he later moved to Toronto), despite the fact that it puzzled and probably infuriated Hollywood execs. He didn’t have a lot of use for them, anyway.

“I guess I just don’t fit in the Hollywood system,” he told me. It was a hell of an understatement, all things considered. The downside of it was that the movies he didn’t get to make far outnumbered the movies that he did. But the ones he did? They made it all worth it.

As he is eulogized this week, and hopefully long after, people will focus almost entirely on his zombie movies. That’s fair enough—he literally invented them. Zombie movies as we know them, with legions of the reanimated dead seeking the brains and/or flesh of the living, simply did not exist before his 1968 classic Night of the Living Dead. He created the most potent movie monster of the modern era, with the mindless undead a metaphoric blank slate onto which audiences and critics could project endless meanings. And they did, right through it sequels, 1978’s Dawn of the Dead, 1985’s Day of the Dead, 2005’s Land of the Dead, 2007’s Diary of the Dead, and 2009’s Survival of the Dead. His scores of zombie imitators and successors stretch from gory exploitation flicks like 1979’s Zombi 2 (better known in the U.S. as Zombie) to later big-budget blockbusters like 28 Days Later and World War Z—not to mention, of course, The Walking Dead.

But none of his zombie flicks were actually his favorite of his own films; that honor fell to a little gem of a vampire movie he made in 1978 called Martin. A raw, violent and eerily realistic look at a young man (played by Romero regular John Amplas) who thinks he is a vampire, the film nimbly sets up the question of whether he really is one, and then finds ways to turn that question on its head over and over. Martin is still moving, shocking and unique today, and is the perfect example of how strange and wonderful Romero’s filmmaking was, especially early in his career.

“I would say Martin is my favorite,” he told me. “First of all, we really had, as my First Assistant Director would say, ‘gelled as a unit.’ We knew more of what we were doing, and it was terrific. I just loved it. I think that film comes closest of anything that I’ve done to matching what was on the page and what was in my mind when I was putting it on the page.”

While any time is a great time to revisit Romero’s zombie films, the “Godfather of the Dead”’s contributions to the horror genre ran even deeper, and I hope film fans take the time to revisit his other works like Martin, as well.