On a crisp and unusually quiet Saturday morning, I arrive at the Martin Luther King Jr. Branch of the San Jose Public Library. I’m there to meet Elena E. Robles, dance anthropologist and expert on Día de los Muertos with over 50 years of investigatory experience.

Robles, a vivid and learned storyteller, has offered to guide me through the vibrant and colorful Art of Remembrance altar exhibit housed on the library’s fifth floor. More than just a seasonal display, this year’s Art of Remembrance is part of the 25th annual Dia de los Muertos celebration thrown by the San Jose Multicultural Artist Guild (SJMAG).

First organized in 1997, SJMAG’s Day of the Dead has grown from a small gathering of around 30 people to now including sponsorships from art museums, San Jose State University and the Mexican consulate. The homegrown annual event survived the pandemic but now faces a new challenge: a search for its next generation of organizers.

Exiting the elevator on the fifth floor, I find an immediate feast for the senses. A pair of grinning skeletons—one with long braids, red lipstick and huaraches, the other in boots and a multihued serape—stand post at the entrance. Garlands of papel picado—colorful tissue-paper flags with intricate cut-out designs—festoon from the tiled ceiling. Just outside the nearby California Room is the elaborate three-tiered altar—or ofrenda—that Robles herself co-designed.

Peppered alongside bookshelves and study nooks are 13 more dynamic displays, each thoughtfully arranged by local artists and students. Nearby gallery walls feature photographs and pencil drawings, and tall glass cases enclose folk art creations. There’s an enticing pair of fantastical large-scale sculptures. Robles, with her calm, welcoming demeanor, guides me through the finer details.

TRADITIONAL ARTFORMS

We pause to take in an intricate sculpture of a Mexican hairless dog. The creature flaunts shiny emerald eyes, a floppy ear and a winged sacred heart near the ribcage. They guard a miniature crypt complete with an archway of chained marigolds. A nearby artist statement says the piece depicts a “dream incarnation of the Xolo.” In several ancient indigenous belief systems, this Mesoamerican canine is known to protect the living and shepherd dead souls to the underworld.

Robles points out that many of the materials used in traditional Mexican handcrafts are relatively easy to come by and accessible to the poorest of the poor. Conceptualized by the Colmenarez-Garcia Family, the sculpture is an artform known as cartonería. It combines cardboard, papier-mâché, wire, paper, glue, acrylic paint and miscellaneous adornments.

Growing up in a small agricultural town in Ventura County, Robles heard about Day of the Dead only sparingly. It wasn’t until she relocated to the Bay Area that she immersed herself in studying the holiday.

“I came here to go to college,” she reflects, “and I became politicized. My eyes were being opened to the world.”

At Stanford in the early 1970s, she took a Chicano Studies course. Her professor’s passing reference to Day of the Dead piqued her curiosity. Her junior year, she took a research trip to Mexico, a pilgrimage that would become an almost annual occurrence. In the years since, Robles has returned almost 30 times.

As we stroll through the exhibit, Robles gestures to a trail of potpourri on the carpeting. In her travels to remote Mexican villages, such trails seldom led her astray.

“I found out about ofrendas because of the petal paths,” she shares. During conversations with a wide range of celebrants, her vantage broadened.

“It’s incredibly diverse,” she reflects of the holiday. “It’s amazingly connected to the philosophy of life, history, economics, social justice and family values. It’s just so broad. It’s as broad as the people who celebrate it.”

While she emphasizes that Day of the Dead is grounded in tradition, she makes an important note: “Tradition doesn’t mean everything stays the same,” she offers. “It means there are still those webs of connection.”

She also emphasizes that the rituals associated with Día de los Muertos resonate broadly. “Honestly, we are surrounded by altars,” she says, noting their prevalence across cultures and religions. We swap examples of the unexpected places we’ve spotted them, from fast food restaurants to the eaves of local grocery stores. And then there are the roadside memorials featuring prayer candles and memorabilia that loved ones create after an auto accident. “They’re everywhere around us right now,” she affirms. “If you’re looking for altars, you’ll see them.”

A QUARTER-CENTURY

Robles is one of several key organizers—all upwards of 65 years old—of San Jose’s longest running Día de los Muertos celebration. Hosted by the San Jose Multicultural Artists Guild (SJ MAG), the event has an intentionally cross-cultural twist. Aztec dancers, folklórico performers, stilt walkers, belly dancers and lion dancers have all shared the bill at the festival’s stage.

“We made it multicultural on purpose,” reflects Arlene Sagun, SJ MAG’s executive director. She notes that, within San Jose’s ever-shifting demographics, there are ceaseless chances to appreciate how different cultures care for their dead.

Owing to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and associated red tape, there’s no procession this year. Still, SJ MAG has managed to curate a wide range of virtual and in-person offerings.

The festivities kicked off with a family-friendly online event last Saturday, featuring a host of streaming performances and demonstrations. In lieu of the wildly popular children’s camp, Sagun made more than 500 art kits to distribute to local kids. There are affiliated in-person events at the San Jose Museum of Art and Children’s Discovery Museum on Oct. 29 and Nov. 5, respectively. Lastly, there’s the altar exhibit which runs at the San Jose Public Library through Nov. 4.

THE DAY EXPLAINED

First celebrated by the Aztec, Toltec and other Nahua people, Día de los Muertos goes back several thousand years. Today’s observers ring in the holiday on Nov. 1 and 2. Owing to the history of colonialism, it occurs in tandem with a pair of Catholic death-related feast days: All Saints Day and All Souls Day.

“Basically, it’s Memorial Day but in Mexico,” says Rick Moreno, a musician, dancer and visual artist who has been building public altars and co-organizing local celebrations since the late 1980s. “You’re remembering all the people that have passed.”

Moreno emphasizes that there are no strict guidelines for who Dia de los Muertos participants can honor.

“It’s anyone who’s influenced your life in a good way,” he says. “Let’s say it’s your grandma or a famous artist–whoever it is that you idolize or respect. The only rule is they have to be dead.”

Because of its proximity to Halloween, the holidays often get conflated. Moreno clears up the confusion.

“We don’t dress up as monsters,” he says of the bright costumes and skull-like face paint that give the festivities their world-renowned flair. “We dress up as if the dead have come back.”

What’s more, the parties, processions, artwork and rituals treat death with both solemnity and joy.

“It’s sentimental,” Moreno explains, noting how humans experience a shared longing to be reunited with their dearly departed loved ones. “It’s also two-sided,” he adds. In addition to prayers and remembrances, there are parties and parades. “You’re out there having fun with death and even making fun of it.”

Moreno erected his first altar just over 30 years ago. At the time, downtown San Jose’s St. Joseph’s Cathedral was getting restored. With the niches temporarily vacant of religious statues, Moreno and his friend Frank Frausto had an idea for how to refill them. Their altars drew great interest from local parishioners. A decade later, he hosted friends and passers-by for an annual celebration in his gallery and frame shop. Attendees, he recalls, were amazed by the grand event.

“We became educators,” he says of his contemporaries who put on public events back then.

SMALL STARTS

Sagun describes how in the early days of SJMAG’s Day of the Dead celebration there’d be as little as 35 or 40 people in the procession.

“When it ended at the Mexican Heritage Plaza, we had a little chocolate and pan dulce and we were done,” she recalls.

But the event has expanded much since those small-but-mighty beginnings. Soon, a host of local groups would sign on as collaborators: the San Jose Museum of Art, the Children’s Discovery Museum, Teatro Visión, the Mexican consulate and the San Jose Public Library to name a few.

The venue has changed as well as the size of the crowd. In 2019, over 1,000 celebrants joined in the fun. The vibrant procession kicked off at City View Plaza and wound down San Fernando Street to the Martin Luther King, Jr Library. An outdoor festival followed, featuring food, music and dance. Among the performers, more than 200 Aztec dancers.

“From two blocks away you could hear the pounding of drums, the pounding of people’s feet,” Sagun describes. “And that conch shell! You better believe the spirits are coming out. I don’t care if you believe in a higher power or not. It’s there and alive and in color.”

She emphasizes that part of an equitable endeavor is to ensure, via behind-the-scenes fundraising, that artists get paid for their work. “That includes the curator, the altar artists, the performers and anyone who’s doing business with me.”

During these pandemic years, the festivities have had to go largely virtual. Mercifully, Sagun and her collaborators were able to improvise and spot a silver lining.

“When you’re performing outdoors, you can’t really do theater,” Sagun reflects. “They can’t hear you. Your voice carries off in the wind.” With cameras, they were able to engage new kinds of performers like storytellers and magicians. An instructor from the San Jose Museum of Art walked home viewers through the steps of fashioning homemade glittery sugar skulls.

For Sagun, another unexpected connection to Day of the Dead came to light in 2018. On her deathbed, her mother shared a startling fact. As farmers in Texas, their family’s crops included acres upon acres of marigolds. They’d sell them to locals who would then incorporate the orange blossoms into their altars.

THE ART OF REMEMBRANCE

The altar exhibit is an especially stimulating component of the celebration. Patrons can peruse the exhibit at their leisure during library hours until Nov. 4.

Kathryn Blackmer Reyes, Director of the Africana, Asian American, Chicano, & Native American Studies Center (AAACNA) at SJSU and an SJSU librarian, stresses that the viewers are as important to the impact of the artwork as the altar-makers. That so many of them are students and that the experience is woven into their education, strikes Blackmer Reyes as particularly special. During her shift, she often overhears young people discussing the pieces on display.

“I hear students say, ‘Do you celebrate this? Does your family do this?’ It’s about making room for those conversations,” she says.

While some artists may not see the library as the most high-brow of galleries, Blackmer Reyes says it has its own unique value.

“It’s not an exhibit that requires you to have a cache as an artist,” she explains. Several of the more personal altars highlight social inequities, a quality Blackmer Reyes sees as distinctly Mexican-American.

“Chicanos have taken altar-making to include not just the artistic value but also the political value and the discussion of social issues,” she states.

Elena Robles has a theory about why activism and Day of the Dead are so linked. Social justice, she points out, is often moored to bereavement.

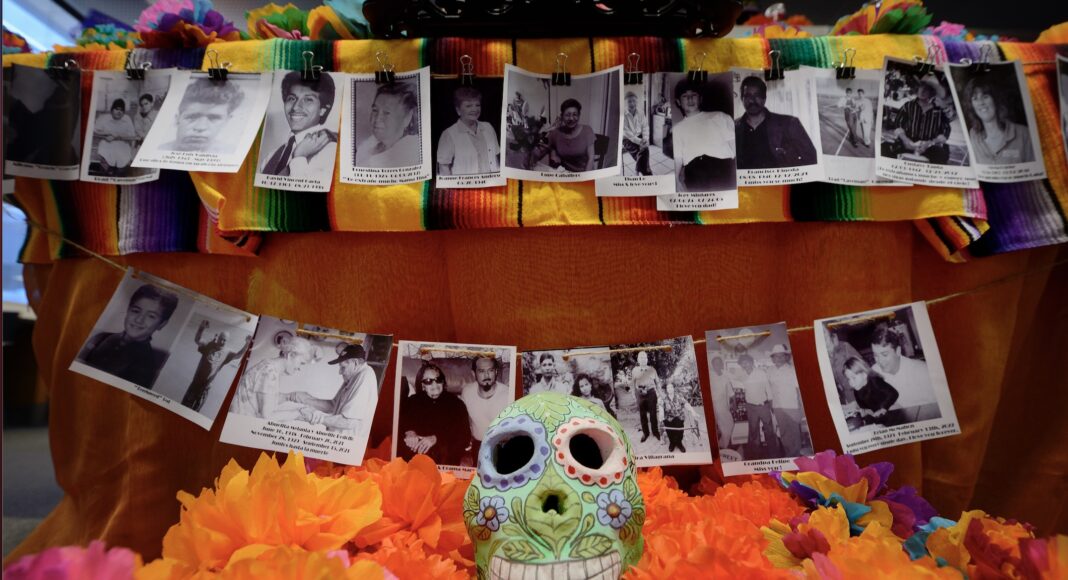

“You lose a right, you lose a person,” she says. “My favorite altar last year was dedicated to people who have been shot by the police in San Jose. I’ve never seen so many pictures in my life.”

GRAVESIDE MEMORIALS

The act of celebrating and caring for one’s dead, Blackmer Reyes says, is a learned process.

“As a child, I went to the cemetery in Mexico,” she remembers. “To me, the simplicity of cleaning a gravesite, putting fresh flowers there, is all part of that sentiment. You’re spending time with your loved ones. That’s really important. Something that I feel strictly that I need.”

Rick Moreno has a similar experience.

“In Mexico, people go to the graveyard at night to sit around and play music,” he shares. “They light candles. It’s a big get-together for the family to tell stories about the person who died.”

He notes that such a celebration is less possible in the US, where cemeteries lock up after sunset.

“It’s different here,” he reflects. “We just have to adapt.”

Near the exhibit’s entrance on the library’s fifth floor, a video screen loops a slideshow of photographs from an ornate cemetery vigil in Michoacán. A local photographer and journalist, Mary J. Andrade captured the images. Like Elena Robles, she has spent decades researching Day of the Dead in different regions, charting the subtle ways the traditions have evolved.

In Michoacán, Robles shares, locals prepare an offering of food. In the evening, they gather to partake in a communal feast. Neighbors and friends eat, gossip and visit with one another, lit by candles amidst their loved ones’ graves.

“Everyone’s celebrating a reunification with the souls and the memories,” Robles says.

THE COCO EFFECT

At least two of the exhibiting artists—photographer Mary J. Andrade and SJSU lecturer Maria Luisa Colmenarez—were cultural advisors on the Disney film Coco. At Arlene Sagun’s urging, Rick Moreno even contributed a Coco-inspired sculpture to this year’s display.

“They couldn’t have done a better job,” he enthuses about the film.

Fashioned of cloth, chicken wire, foam and other materials, Moreno’s piece features Miguel, the story’s protagonist, atop a day-glo orange alebrije (a form of traditional folk art, alebrijes are brightly painted fantastical creatures carved from soft wood). In Coco’s cinematic universe, the alebrije arrives to transport Miguel to the Land of the Dead.

Coco received worldwide acclaim upon its release in 2017. Even so, some viewers felt it contributed to the commercialization of the holiday. In 2013, the Walt Disney Company faced widespread opposition when they attempted to trademark Día de los Muertos and Day of the Dead across multiple platforms.

“Our spiritual traditions are for everyone, not for companies like Walt Disney to trademark and exploit,” wrote Grace Sesma, a curandera (traditional healer) and educator who started a Change.org petition to protest the effort.

When asked about Disney’s attempt to secure exclusive rights to the holiday’s name, Robles sums it up simply.

“Greed,” she reflects, “is the downfall of humanity.”

Controversies aside, Moreno appreciates how the film has brought new celebrants into the rituals and festivities.

“Everything changes,” he reflects. “Hopefully for the better. And I just want people to participate.” He says he would never look down on someone for putting a new spin on their practices.

“We’re kind of creating our own tradition. As people get more into it, you’re going to see more creativity.”

NEXT GENERATION

With another Dia de los Muertos passing, the San Jose Multicultural Artist Guild is beginning a search for new leadership.

“All of us have been doing this for 30 or 40 years, and none of us are getting any younger,” Sagun says.

She hopes to mentor a young leader who wants to carry forward the vision she and her collaborators have fine-tuned over many years. “I don’t want it to be commercial,” she cautions. “And I want it to be all inclusive of everyone.”

“Arlene, from the beginning, was dedicated to making it a community expression,” Robles shares, noting the multicultural emphasis. “I hope it will remain this open-minded of a community event.”

She underlines the importance of keeping things simple and accessible, two of the holiday’s defining features.

“We have to make what we do sincere and unfettered by cost.”

Whoever decides to take up this charge will be learning alongside seasoned community organizers and scholars.

“It took me a while to embrace that I’m now an elder,” Robles says. “You don’t know what an amazing life I’ve had.”

The holiday, she notes, helped her to process her own mortality as well. She jokes: “I tell my students, when Miss Elena’s gone and you want to remember me, you have to put a diet cola and a chocolate on the ofrenda.”