You’ll recognize Grant Wood’s name first in the San Jose Museum of Art’s “Crossroads” exhibit. He’s the painter made famous by American Gothic (1930), the one with the pitchfork standing upright between a farmer (modeled after the artist’s dentist) and his daughter (after the artist’s sister Nan). But this painting doesn’t appear in the show.

“Crossroads: American Scene Prints from Thomas Hart Benton to Grant Wood” is devoted solely to lithographs, etchings, and wood engravings by Benton, Wood and their lesser-known contemporaries.

In fact, there are only two works by Benton and three by Wood, whereas Leon Gilmour and Louis Lozowick, neither household names, are represented by almost a dozen each. The drawings in Benton’s lithographs Cradling Wheat (1939) and A Drink of Water (1937) undulate across the canvas. He sketches the world in a gentled state of fluidity, as if he could see the liquid motion of the planet moving beneath his feet. Grant Wood’s lines are more defined, if not entirely angular. In Seed Time Harvest (1937) and Tree Planting Group (1937), his human figures are stolid. They are aware of their spines and use them to stand up straight. Both men draw recognizable versions of mythical American farm lands.

But juxtapose Leon Gilmour’s work against theirs and these same landscapes suddenly intensify. He envisions rural life, and its transition into an urban one, as something stark and alien. His black-and-white engravings remind the viewer that before graphic novels existed artists told complex stories without words. In two of them, Gilmour abandons any nod to realism. If you were to categorize Outposts (1936) and Let the Living Rise (1937), they veer toward the expressionist work Gods’ Man by Lynd Ward (1905-1985). The characters in them also prefigure Doctor Manhattan, Alan Moore’s superman from The Watchmen.

Outposts is a strange portrait of twinned bald men. In the center of the frame, one cranes his neck up, the other stares directly in front of him. They overlap each other, as if conjoined, and appear to be growing out of a primordial ooze. Like the statues on Easter Island, they stand disembodied from the neck up. The night sky swirls with comets and stars, but both men reveal no awe or emotion of any kind. And they may be blind. One of them returns as a naked figure in Let the Living Rise. His body lies outstretched as one hand summons a volatile windstorm along the horizon line. Growths of cartilage have formed on the man’s back. He’s not unlike the Engineer in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, related to mankind but oversized and threatening.

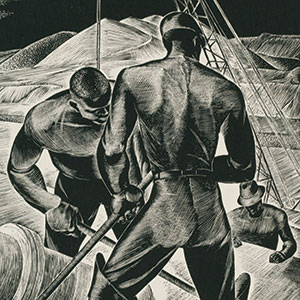

However, these are the exceptions to the rule. The rest of Gilmour’s work is a series of botanicals and also finely wrought landscapes (save for one compelling urban scene in Cement Finishers). But once you’ve taken in the bald men, even the cactus flowers in Christmas Candles (1936) take on and give off an eerie effect. Lozowick too focuses on oddities (note the addition of a random squirrel next to a man passed out on a park bench). But his strongest lithograph is Subway Construction (1931). He brings an architect’s eye to every beam and girder. His other pieces are hazier and lack this lithograph’s rigor and clarity.

The artists collected here all share some relationship with the “American Scene,” the naturalist style of art and painting that includes Social Realism and American Regionalism. Crossroads ranges in time from 1905 to 1955, roughly the first half of the 20th century. The America they depicted back then was still in formation. To our eyes, these drawings present a ghost world that’s long gone. If they were placed together as panels in a book or graphic novel, they’d tell the story of our great migration from the open spaces of a hushed world to the coming noise and rush of the 21st century.

Crossroads: American Scene Prints

Thru Jul 8, $10

San Jose Museum of Art

sjmusart.org