Memories come from the strangest places. The recent image of a bank robber fleeing into the Santa Cruz Mountains and the subsequent police manhunt drove me to remember when I first became interested in exploring that same terrain.

As a little kid in the mid-1970s, one of the first travel books I flipped through was a mammoth hardback coffee-table tome called Back Roads of California by Earl Hollander.

Everyone’s parents seemed to own the book, featuring Hollander’s relaxed, genteel pen-and-ink drawings of various locales from the mountain side roads of California, “beyond the subdivisions” as one page quipped. Hollander drew the scenes and supplied the accompanying anecdotes by hand on every page. In the pre-Internet era, his Zen-like approach taught me to search outside mainstream paths for inspiration. This was decades before GPS and long before Bay Area Backroads appeared on television.

Naturally, I fixated on the section about the Santa Cruz Mountains. In retrospect, this was probably the first time I ever learned about the Almaden Quicksilver Mines, Summit Road, Mountain Charlie Road or the back way over Mount Hamilton to Highway 5. I was way too young to drive, but I worshipped that book. I perused it over and over.

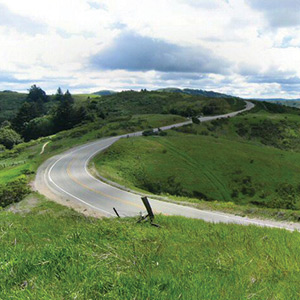

As a kid, I was already fascinated with maps, and one page in the book showed how to depart from Blossom Hill Road—just down the street from where I grew up—and then proceed down Almaden Expressway, to McKean Road, to Uvas, and then into the cold green shadows of the Santa Cruz Mountains. This was back when people still occasionally referred to Almaden Expressway at County Road G8. Hollander’s rustic sketches only made the book more intriguing. I learned that I could explore, travel or embark on a mysterious journey without having to venture great distances. I could be a travel writer in my own backyard.

On one particular page Hollander drew the ruins of cattle millionaire Henry Miller’s estate near Mount Madonna, providing this anecdote: “I sketched as 2 truant young boys climbed neighboring redwood trees. I heard one say, ‘Isn’t this more educational than spending a day in that old school?'”

I always wondered who those kids were. Now I wonder if they’re still alive, or if they ever learned that Hollander immortalized them in his book. In any event, they, like Hollander, inspired me. In grade school, I often felt like I already knew what the teachers were trying to explain, so I grew bored. I wanted to travel and augment my imagination. As I grew older and began to drive, I developed an intrinsic desire to navigate the ignored streets of my native turf, whether that was the mountains or the awful subdivisions. Again, it felt natural, just like drawing or playing music. I spent a lot of gas money driving around the Santa Cruz Mountains just to find out where the roads went.

By the time I became an adult—if I even qualify, that is—the phrase “off the beaten path” was ingrained in me. It was not some alternative way of traveling. For me, it became a metaphor for many ways in which this column emerges.

In that sense, the original book, Back Roads of California, instilled enough of a traveler’s mentality to eventually generate several columns. For instance, on another page, Hollander wrote about first discovering the history of the notorious Mountain Charlie, as well as the road named after him. This was before the legendary chapter no. 1850 of E Clampus Vitus, a.k.a. “The Clampers,” were able to erect plaques at various celebrated points of historical interest related to Mountain Charlie. Hollander’s book was the first place I read about this stuff, so, decades later, when infiltrating the Clampers for several columns in this space, I knew what they were talking about. We were kindred spirits.

Those were just a few columns among many that I can trace back to that book. I’m grateful to be an explorer that found a way to write about my experiences. Writing kept me off the criminal path. I don’t need to hold up a Bank of America. I rob the bank of ideas instead.