Stay Hungry | Selling a Vision | Animated Character | Hits & Misses | How I Got Dissed By Steve Jobs

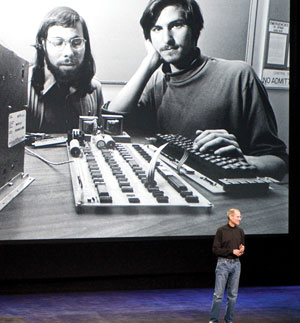

IN June, 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak walked into the office of the Silicon Valley public relations firm Regis McKenna Advertising. It was their second visit with Bill Kelly, who had come to see them in Jobs’ parents’ garage a week earlier, but on this visit they would be joined by McKenna himself.

“Steve came in, and I can remember him sitting in our little conference room and him talking about children using computers, and teachers using computers, and business people using computers,” McKenna recalls.

The idea sounded a little nuts. The machine Woz and Jobs were selling, the Apple I, was little more than a motherboard. It included no monitor, no keyboard and no programs and no mouse. It was a toy for hobbyists.

But in addition to their pre-assembled kit computer, Jobs was also selling a vision. And that’s what got the executives from the tech sector’s leading ad firm to sign up.

Long before the stage-directed spectacles of the product launches, Steve Jobs was the world’s first and best high-tech evangelist (a term later coined by Mike Murray of the Macintosh Division). What Jobs was selling was the idea that computers could be powerful tools for the dissemination of knowledge and power, and that everyone in the world should have one.

The following day, Bill Kelly, a youngish ad man at McKenna, sent a letter to his bosses letting them know that he wanted to work with the two even-younger guys from Apple. And because Apple had no money, he recommended that the agency do so on spec. He conceded that this might seem risky—the two men were very young. “On the other hand, [Nolan] Bushnell was young when he started Atari.” Regis McKenna, initially skeptical, agreed.

That letter is now housed with the Apple collection at Stanford University, part of the Stanford Silicon Valley Archives, a gathering that includes internal memos, email logs, interviews, user-group newsletters, newspaper ads and in-house ad campaigns, as well as thousands of formerly Apple-eyes-only documents.

A couple of weeks after Jobs resigned as CEO, I requested five boxes of documents from the collection and visited the reading room at the elegant old Green Library to go through them. What I found looked less like a company history and more like documentation of the birth of a historic movement.

In memos describing technical requirements and price-points for new products, debating design features, colors and fonts, or just plain spitballing about a piece of theoretical engineering, the Apple team’s leaders come off the page like post-’60s technological philosophers—big-thinking, free-wheeling engineer-monks devoted to a radical, mind-blowing vision.

A statement from a one-page internal memo laying out “Apple Values,” possibly authored by Jobs himself, proscribes a corporate culture that “encourages creativity [and] freedom of professional expression, and rewards both the pursuit and the achievement of excellence.” Another one-pager, headlined “Apple People,” specifically describes a mission to create “products that are elegantly simple, feature rich, and delightful to own—for people who learn, create and communicate.”

Key Player

In the days since his death, Steve Jobs is being heralded as, among many other things, the greatest inventor of modern times. Last week, SJSU professor Richard Stross wrote a piece for The New York Times comparing Jobs to Thomas Edison. But while Jobs deserves credit for bringing the world some of the coolest products ever seen, he didn’t invent any of them.

The Apple I and II used innovative tricks invented by Woz. The Mac was the brainchild of Jef Raskin, a technical writer and human-interface expert who was with Apple from the days in the garage. The Graphical User Interface and mouse were both conceived at Xerox PARC. The patent for the MP3, which underlies the iPod, is held by the Fraunhofer Institut Integrierte Schaltungen. Touch-screen, which made the iPhone and iPad revolutionary devices, was developed by NYU mathematician Jeff Han.

While Jobs was not personally responsible for any of these specific inventions, there’s no doubt that he played the key role in all of their realization. Jobs’ vision was paired with a genius for industrial design—he knew what consumers wanted way before they did—and with an unswerving commitment to quality.

Stanford historian Henry Lowood, curator of the archives, says Jobs’ greatest strength, in the long run, was not as a product designer or marketer, but as a corporate chieftain.

“Probably the most amazing thing about Steve was his skill as an executive,” Lowood says. “He was brilliant at having a clear product vision, and executing that vision with almost no variation or play.”

Lowood says that Jobs’ uncompromising resolve may be part of what made him so good at what he did: “This salient skill of his—to stay focused and execute—it’s almost symbolized in Apple products. Like Steve, they have very low tolerances. That defines what makes it so easy to recognize an Apple product.”

Writing in 1978, Jef Raskin tried to imagine a future in which computers were everyday appliances, networked so people could communicate vastly and easily. “Will the average person’s circle of acquaintances grow? Will we be better informed? Will use of these computers as an enlightenment medium become their primary value? Will they foster self-education?”

While some of Raskin’s questions can be answered today, it’s clear that the future he imagined, which surely sounded then like science fiction, has come to pass. And it’s likely that one man, more than any other, made that happen.