Last week, San Jose State University celebrated one of the most historic anniversaries in campus history, and perhaps even San Jose history as well. Exactly 50 years earlier, on Oct. 16, 1968, SJSU Spartans Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood on the Olympic podium in Mexico City after winning gold and bronze medals in the men’s 200m event.

During the national anthem, Smith and Carlos each bowed their heads and raised a black-gloved fist into the air, reflecting the strength of the human spirit and cementing what’s now one of the most iconic images in Olympic history. The third person on the podium, Australian Peter Norman, stood motionless with the silver medal around his neck, but in full support. Smith and Carlos were also part of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), led by SJSU sociologist Harry Edwards, a group formed to expose how the US exploited black athletes, a group that almost boycotted the 1968 Olympic Games.

Last week, newsbytes about the 50th anniversary events at SJSU came from all over the world, inside and outside of sports. On Wednesday, three provocative panel sessions reflected on the history and future of athlete activism, all organized by SJSU’s Institute for the Study of Sport, Society and Social Change. The next night, Smith and Carlos together received the annual Tower Award, the highest accolade given by the university.

Each panel session provided inspiring stories, but the first panel, titled “The Voices of 1968,” included not just Smith and Carlos but also Wyomia Tyus, the first person ever to win consecutive Olympic gold medals in the 100-meter dash, in 1964 and 1968. Tyus was in the stadium watching Smith and Carlos during their historic protest, noticing how they walked out to the podium without shoes, and then raised their fists into the air during the national anthem.

“The stadium got completely quiet,” Tyus recalled. “It was just eerie, just no one was saying anything. And as they continued to play the national anthem, you could hear people talking and then you could hear people booing, you could hear people whistling, you could hear people cheering, and I just started feeling, ‘Oh man, I hope nothing happens to them. They’re right out in the open. I hope no one does anything.'”

By now, reporters have asked Smith and Carlos ad nauseam about those moments, and there on the stage, both of the legendary track and field medalists spoke about the eerie silence. They cast the events in spiritual terms of suffering, pain, sacrifice and redemption. They claimed fear was never a factor, as their lives were already being threatened due to the potential boycott.

Carlos recalled the eerie silence with a tinge of gallows humor: “Before we went out, I told Tommie, I said, ‘Tommie, they’ve been threatening our lives.’ I said, ‘Remember, man, we are trained to listen to the gun. When we go out and we do what we do, everyone is going to be in shock.’ And that’s what [people are] talking about in terms of that void. Everyone became deadly silent, they were in shock, they never seen anything like this. And I said to Tommie, ‘If they’re going to shoot, they’re going to shoot in that void. Listen for the gun. We’ve been trained.'”

Also on the panel was Paul Hoffman, member of the Harvard University rowing team, an all-Caucasian group that supported the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Hoffman was the one who gave an OCHR button to Peter Norman as the Aussie walked out to the podium. Norman then famously wore the button during the protest.

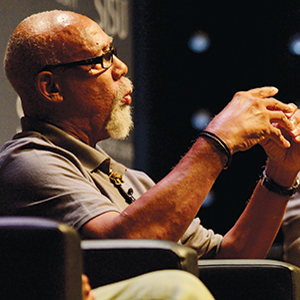

“It’s extremely rare that you have the actual actors and participants in a historic moment, a historic year, on stage to discuss their experiences and the impact of half a century of thinking about that impact,” said Edwards of the morning’s discussion.

The next night, Smith and Carlos received the Tower Award to a standing ovation. At the reception, I told Carlos that I was not yet alive during the 1968 Olympics, but I was in the womb, showing my support. I was listening for the gun. And he laughed out loud.