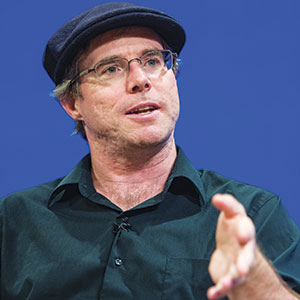

Nothing Andy Weir says in his calm, understated, chuckling-at-himself voice can begin to explain how this unassuming software engineer who lives in Mountain Viewjust another productive drone in the Silicon Valley hive for countless yearsturned out to be the One.

He has no idea himself. He keeps waiting for the chiming of his alarm to jolt him from what must surely be a dream. None of this could possibly have been realnot the giddy experience as an unpublished writer posting the chapters of his geek-out novel The Martian on his personal website, one by one, à la Charles Dickens, and finding that thousands of people were grabbed by his story and wanted more; not a sudden publishing deal with Random House; not No. 1 bestseller status, not the movie starring Matt Damon. And not the chance to publish his second novel, the new moonscape crime drama Artemis.

“It was a charmed existence,” Weir told me in a recent phone conversation, with a combination of openness and self-mockery. “It was really awesome. I tried to be as grateful as I could at the time because I told myself, ‘It’s probably not going to happen again.'”

There was silence over the phone as he let it sink in that he was utterly, painfully sincere in having no idea if lightning could ever strike twice for him.

“Of course I’ve got the ‘impostor syndrome’ thinking. I’m like: I don’t know what I did right. Really, I don’t know what the hell I’m doing. All I can do is write stories that I myself would enjoy reading.”

Weir is onto something there. If more writers would focus on telling stories they themselves wanted to read, the world of writing would do a much better job of connecting with readers, absent many an unfortunate detour through the landscape of the mannered, the trendy, the showy, the unreadable. It’s like cooking: A good place to start is whipping up a meal that tastes delicious to you. At least one person is going to be happyand, chances are, others will as well.

Not every fan of The Martian loves Artemis, which surged to the top of the bestseller lists as soon as it was published in November, reaching No. 6 on the New York Times hardcover fiction list its first eligible week, and it might be a while before any undergraduate seminars focus on Weir’s literary merits. He’s not a once-in-a-generation literary talent like Jennifer Egan (Manhattan Beach), Viet Thanh Nguyen (The Sympathizer) or Nathan Hill (The Nix). Andy Weir is the One because he’s given us a feel-good reminder of the power of the imagination, and he can inspire anyone and everyone to pursue their own writing, maybe even becoming rock-star huge.

Weir has talent, but mostly he has ideas. He has no fancy degrees, no privileged bond with a great-writer mentor; he’s your basic writer next door.

Weir has gone from nowhere on the literary map to front and center, all because he’s a guy who loves stories, a guy who believes in the power of what used to be called daydreaming. His amazing run of success can and should serve as inspiration to anyone with an idea, anyone wanting to let their mind race, anyone who believes in the power of an imagination driven by a sense of fun and unfettered by the closed-window heavy breathing of writing-seminar “notes” or trends in writing.

Weir is the One, as well, because he’s a perfect test case for the way the internet now makes it possible for an individual with passion and stamina to put out a story that might resonate with others. He’s the future of publishing, or at least its avatar, not because of his prose style or his flawless psychological insights into his characters, but because he understands the importance of taking a reader for a ride. (Cue up appropriate Jimi Hendrix lyrics.)

One of the pleasures of reading an Andy Weir novel is the certainty we have that we know exactly who Weir is, just from the story he tells. Yes, like Mark Watney, the main character in The Martian, and Jazz Bashara, the straw that stirs the drink in Artemis, he’s a sarcastic, wisecracking kind of guy. Yes, he loves science, and puts in the time to get it right. I even had the feeling I could picture Weir in his childhood, out in a California field somewhere, firing off Estes model rockets into the sky.

“Did you ever play with model rockets?” I asked him, just for fun, knowing full well he’d say yes.

“Estes! Big time!” he said. “I designed my own.”

Once again, in Artemis, Weir soars. He blasts off, delivering a breezy joy ride sure to appeal to a wide audience, especially anyone who shares his enthusiasm for what he calls his “holy trinity” of major influences: Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke.

I don’t read much science fiction nowadays. Actually, as the father of two small girls, busy as the co-director of the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods writers’ retreat center in Soquel, I don’t get much time to read books at all. So when my older brother Greg, a lifelong fan of science fiction, emailed me a couple years ago and told me I needed to read a book called The Martian, I ordered it right awayand burned through it in a rush of pure joy.

Weir’s follow-up is a far more ambitious undertaking. For me, it didn’t have quite the feel of uninterrupted dream that The Martian did, pulling you along inexorably, but in some ways I like Artemis better. It doesn’t feel like a one-off. It feels like a conduit into an entire world of revving imagination, akin to the Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke I read in my teens. For me, this kind of storytelling has power and social relevance. A lot of perspective can be packed into stories that have the liftoff of science fiction.

Artemis is a tale all about the kinds of power plays that take place when deals have to be made to handle population growth despite scarce resources. Sound relevant and contemporary? Californians understand this very well, and setting the story on the moon in some ways harked back to an earlier era of expansion in this state.

“I wanted the book to be about mankind’s first city that isn’t on Earth, and to me it was very obvious that that was going to be on the moon,” Weir told me. “Colonizing Mars before colonizing the moon would be like if the ancient Britons colonized North America before they colonized Wales. I love stories that take place in off-world colonies. There’s the frontier spirit you see in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, but I also thought of lesser-known Heinlein, like Farmer in the Sky, which is set on Ganymede. We’re basically talking about a frontier society in space.”

Which takes us back to California. As the novel was taking shape in Weir’s imagination, he found himself drawing inspiration from movies even more than science-fiction novels, specifically a 1974 classic starring Faye Dunaway and Jack Nicholson, and set during California’s water wars of the early 20th century.

“One of my main influences was the movie Chinatown, which is really about the growth of a city and everything that has to happen for that to move forward,” Weir says. “When I was working on Artemis, I kept thinking: this is similar to Chinatown. So I watched the movie again.”

It’s a great movie, with a script from Robert Towne that’s considered one of the best in the history of cinema. No one who has seen it will forget the younger Nicholson with tape on his nose, playing Jake Gittes. I highly recommend reading the Weir novel and then watching the movie again as a way to explore how one creative work can infuse and inform another. Both have about them a feeling of gradually uncovering deeper truths.

In the case of Artemis, the drama also hinges on a power play over resources. It’s complicated, but here are the basics of the setup: Jazz Bashara is estranged from her father, a master welder, who like her lives on a small colony on the moon called Artemis. She works as a portera low-income, low-profile job that serves as a useful cover for her other occupation: a large-scale smuggling operation with the help of an Earthside pen pal she’s been close to for years. Through her smuggling operation, she meets a wealthy businessman named Trond Landvik who offers her a million credits to engage in some major sabotagean insanely difficult mission that she, wanting the money, decides to accept. She comes up with a good plan, and almost pulls it off, sabotaging all but one of the automated mining harvesters operated by Sanchez Aluminum. Then she goes to see her wealthy businessman clientonly to find him murdered. It turns out that the enforcer of a Brazilian crime syndicatewhich, this just in, owns Sanchez Aluminumhas murdered the businessman and is now after her, only he’s a little off his game in the low gravity of the moon, putting him at a disadvantage. By teaming up with her estranged father and a lovable geek named Martin Svoboda, who becomes an unlikely love interest, Jazz brings her schemes to an unlikely conclusion. Anyone who says they saw it all comingthe kind of hair-ball analysis regularly coughed up onlineis full of it.

Weir’s most daring choice with Artemis was choosing to narrate his book in the voice of his female lead character, Jazz. Even many fans of the book have some issues with a middle-aged white guy trying to write in the voice of a woman in her 20s. Writing in the New York Times, for example, N.K. Jemisin went glib: “She talks and acts like a Middle American white man.” Even Kirkus, in a swipe I have to call bizarre, took a shot at Weir for thanking his publisher and U.K. editor and other women in his acknowledgements “for helping me tackle the challenge of writing a female narrator.” What’s wrong with that? Kirkus thought acknowledging help made it sound “as if women were an alien species.”

Hold on there. Reviewers often don’t know much about how books actually get writtenthey’re more the sit-back-and-snipe typesbut fine-tuning voice takes work, and one always asks for help. If you’re narrating a book with a character from England, and you yourself are from California, you get help to hunt for anywhere you can improvethat doesn’t mean you think people from England are an “alien species.”

Weir couldn’t win, in other words, but he knew that going inand he’s disarmingly open about how harrowing it was to go with his impulse to build the book around a young woman. “That was probably the biggest challenge in the book for me,” he told me. “I don’t know if I did a good job or not. Some people have strong reactions, saying, ‘This is horrible. Andy Weir doesn’t know anything about women.’ There are demographics that would never accept a female lead written by a man under any circumstancesyou may not have a female lead written by a man, period.”

He’s right about that, of course, but he’s surely going to piss some people off by saying so. It probably helps his cause that he’s matter-of fact-and mild about the observationnot angry, not combative, just accepting of conditions, like an engineer planning a rocket launch.

“I was interested in developing a female character who was a flawed person, with shady morals, who makes bad life decisions,” he says. “These are all character flaws that if I had applied them to a man, people would say, ‘OK,’ but applied to a woman, some people say, ‘All women aren’t like that.’ The Martian had no character depth. No one accused it of being literature. This time, I wanted deeper characters. No one’s going to talk about it with the Pulitzer committee, but I hope I stretched myself.”

They are interesting quandaries. Weir wrote the book knowing full well that given the proclivities of Hollywood producers, and given the success of the film version of The Martian, the new novel he was writing had a decent shot at hitting the big screen. So in writing a vehicle for a sarcastic, flawed young woman character who also happens to be smart, resourceful and complex, he was working in a small way against the historically male-dominated tradition of science fiction, which thankfully has slowly begun to diversify. That said, of course any author is fair game, and if people find some of Jazz’s lines clanging, so be it.

Here’s a pretty good test case: “I stared daggers at Dale. He didn’t notice. Damn, I wasted a perfectly good bitchy glare.”

I thought the line was funny. I thought it came through that Weir was having a lot of fun with his writing. Then again, I am a reader of a similar age and background to Weir himself.

The novel has been optioned, and I’d be stunned if it didn’t hit the big screen with a young actress nailing the part. In fact, I think we’re going to be seeing a lot of Jazz Bashara for years to come. Weir definitely stretched himself here, and I for one am glad he did.

“I really tried to convey Jazz’s flippant attitude,” he said. “It was much harder to write Artemis than The Martian. The Martian was so much more simple. It was a lot of math problems, and I’m good at that. Complex human interaction is more challenging. Mark is more or less flawless. He makes errors, but there’s no moral ambiguity to him. He’s a guy with no personality flaws other than being snarky sometimes, where Jazz has made very bad decisions and most of her problems are self-inflicted. She had everything she needed to get a start in lifea parent who loves her, an education. She still managed to piss all that away.”

Some readers are put off by her endless wisecracking and sarcasm, but again, on the screen that could work out just fine.

“She has a sarcastic sense of humor,” Weir says. “That’s just me. I think everything I write is going to be through that lens, because that’s just who I am … I don’t have an idea what a character looks like. I don’t get a visual. Like when I wrote The Martian and finished, I couldn’t have told you what color Mark Watney’s hair was. Like with Jazz, I don’t see her. I know she has olive skin. I’d like her to be played by a woman who has that skin tone.”

As for what we can expect next from Weir, he’s not going anywhere. The ideas keep exploding out of his active imagination.

“I would love for Artemis to be a series,” he told me. “I’m working on the next book already, just a few thousand words so far. I’m working on that, but don’t want to get too enthusiastic yet. What if people don’t like Artemis? If it goes over well, I can see a whole series of books.”