Instead of hanging around

Silicon Valley and falling into the same funk as his peers, however, Musk decamped to Los Angeles. The conventional wisdom of the time said to take a deep breath and wait for the next big thing to arrive. Musk rejected that logic by throwing $100 million into SpaceX, $70 million into Tesla and $10 million into SolarCity. Short of building an actual money-crushing machine, Musk could not have picked a faster way to destroy his fortune. He became a one-man, ultra-risk-taking venture capital shop and doubled down on making super complex physical goods in two of the most expensive places in the world, Los Angeles and Silicon Valley.

With SpaceX, Musk is battling the giants of the U.S. military industrial complex, including Lockheed Martin and Boeing. He’s also battling nations—most notably Russia and China.

The space business requires dealing with a mess of politics, back-scratching and protectionism that undermines the fundamentals of capitalism. Steve Jobs faced similar forces when he went up against the recording industry to bring the iPod and iTunes to market. The crotchety Luddites in the music industry were a pleasure to deal with compared to Musk’s foes, who build weapons for a living.

With Tesla Motors, Musk has tried to revamp the way cars are manufactured and sold, while building out a worldwide fuel distribution network at the same time. Instead of hybrids, which in Musk lingo are suboptimal compromises, Tesla strives to make all-electric cars that people lust after and that push the limits of technology. Tesla does not sell these cars through dealers; it sells them on the Web and in Apple-like galleries located in high-end shopping centers. Tesla also does not anticipate making lots of money from servicing its vehicles, since electric cars do not require the oil changes and other maintenance procedures of traditional cars. The direct sales model embraced by Tesla stands as a major affront to car dealers used to haggling with their customers and making their profits from exorbitant maintenance fees. Tesla’s charging stations now run alongside many of the major highways in the United States, Europe and Asia and can a hundreds of miles of oomph back to a car in about 20 minutes.

With SolarCity, Musk has funded the largest installer and financer of solar panels for consumers and businesses. During a time in which cleantech businesses have gone bankrupt with alarming regularity, Musk has built two of the most successful cleantech companies in the world. The Musk Co. empire of factories, tens of thousands of workers and industrial might has incumbents on the run and has turned Musk into one of the richest men in the world, with a net worth around $10 billion.

The life that Musk has created to manage all of these endeavors is preposterous. A typical week starts at his mansion in Bel Air. On Monday, he works the entire day at SpaceX. On Tuesday, he begins at SpaceX, then hops onto his jet and flies to Silicon Valley. He spends a couple of days working at Tesla, which has its offices in Palo Alto and a factory in Fremont. Musk does not own a home in Northern California and ends up staying at the luxe Rosewood hotel or at friends’ houses. Then it’s back to Los Angeles and SpaceX on Thursday.

Musk has taken industries like aerospace and automotive that America seemed to have given up on and recast them as something new and fantastic. At the heart of this transformation are Musk’s skills as a software maker and his ability to apply them to machines. He’s merged atoms and bits in ways that few people thought possible, and the results have been spectacular. It’s true enough that Musk has yet to have a consumer hit on the order of the iPhone or to touch more than one billion people like Facebook. For the moment, he’s still making rich people’s toys, and his budding empire could be an exploded rocket or massive Tesla recall away from collapse.

On the other hand, Musk’s companies have already accomplished far more than his loudest detractors thought possible, and the promise of what’s to come has to leave hardened types feeling optimistic during their weaker moments.

“To me, Elon is the shining example of how Silicon Valley might be able to reinvent itself and be more relevant than chasing these quick IPOs and focusing on getting incremental products out,” said Edward Jung, a famed software engineer and inventor. “Those things are important, but they are not enough. We need to look at different models of how to do things that are longer term in nature and where the technology is more integrated.”

The integration mentioned by Jung— the harmonious melding of software, electronics, advanced materials and computing horsepower— appears to be Musk’s gift. In that sense, Musk comes off much more like Thomas Edison than Howard Hughes. He’s an inventor, celebrity businessman and industrialist able to take big ideas and turn them into big products.

Born in South Africa, Musk now looks like America’s most innovative industrialist and outlandish thinker and the person most likely to set Silicon Valley on a more ambitious course. Because of Musk, Americans could wake up in 10 years with the most modern highway in the world: a transit system run by thousands of solar-powered charging stations and traversed by electric cars. By that time, SpaceX may well be sending up rockets every day, taking people and things to dozens of habitats and making preparations for longer treks to Mars. These advances are simultaneously difficult to fathom and seemingly inevitable if Musk can simply buy enough time to make them work. As his ex-wife, Justine, put it, “He does what he wants, and he is relentless about it. It’s Elon’s world, and the rest of us live in it.”

What Musk has developed that so many of the entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley lack is a meaningful worldview. He’s the possessed genius on the grandest quest anyone has ever concocted. He’s less a CEO chasing riches than a general marshaling troops to secure victory. Where Mark Zuckerberg wants to help you share baby photos, Musk wants to, well, save the human race from self-imposed or accidental annihilation.

Things Explode

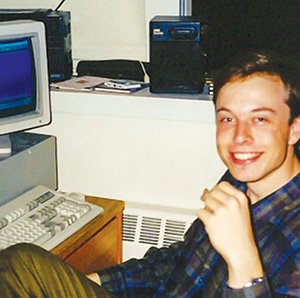

When Elon was nearly 10 years old, he saw a computer for the first time, at the Sandton City Mall in Johannesburg. “There was an electronics store that mostly did hi-fi-type stuff, but then, in one corner, they started stocking a few computers,” Musk said. He felt awed right away.

“I had to have that and then hounded my father to get the computer,” Musk said. Soon he owned a Commodore VIC-20, a popular home machine that went on sale in 1980. Elon’s computer arrived with five kilobytes of memory and a workbook on the BASIC programming language. “It was supposed to take like six months to get through all the lessons,” Elon said. “I just got super OCD on it and stayed up for three days with no sleep and did the entire thing. It seemed like the most super-compelling thing I had ever seen.”

While bookish and into his new computer, Elon quite often led his brother Kimbal and his cousins Russ, Lyndon and Peter Rive on adventures. They dabbled one year in selling Easter eggs door-to-door in the neighborhood. The eggs were not well decorated, but the boys still marked them up a few hundred percent for their wealthy neighbors. Elon also spearheaded their work with homemade explosives and rockets. South Africa did not have the Estes rocket kits popular among hobbyists, so Elon would create his own chemical compounds and put them inside of canisters.

“It is remarkable how many things you can get to explode,” Elon said. “Saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal are the basic ingredients for gunpowder, and then if you combine a strong acid with a strong alkaline, that will generally release a lot of energy. Granulated chlorine with brake fluid— that’s quite impressive. I’m lucky I have all my fingers.”

At 17, Musk left South Africa for Canada. Musk had been pining to get to the United States for a long time. Musk’s early inclination toward computers and technology had fostered an intense interest in Silicon Valley.

After spending a few days in Montreal exploring the city, Musk bought a $100 countrywide bus ticket that let him hop on and off as he pleased. He headed to Saskatchewan, the former home of his grandfather. After a 1,900-mile bus ride, he ended up in Swift Current, a town of 15,000 people. Musk called a second cousin out of the blue from the bus station and hitched a ride to his house.

Musk spent the next year working a series of odd jobs around Canada. He tended vegetables and shoveled out grain bins at a cousin’s farm located in the tiny town of Waldeck. Musk celebrated his 18th birthday there, sharing a cake with the family he’d just met and a few strangers from the neighborhood.

After that, he learned to cut logs with a chainsaw in Vancouver, British Columbia. The hardest job Musk took came after a visit to the unemployment office. He inquired about the job with the best wage, which turned out to be a gig cleaning the boiler room of a lumber mill for $18 an hour.

“You have to put on this hazmat suit and then shimmy through this little tunnel that you can barely fit in,” Musk said. “Then, you have a shovel and you take the sand and goop and other residue, which is still steaming hot, and you have to shovel it through the same hole you came through. There is no escape. Someone else on the other side has to shovel it into a wheelbarrow. If you stay in there for more than 30 minutes, you get too hot and die.”

Elon enrolled at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, in 1989. A deep relationship during this stint in Canada arose between Musk and Justine Wilson, a fellow student at Queen’s with long, brown hair. Musk spotted Wilson on campus and went right to work trying to date her. “She looked pretty great,” Musk said. “She was also smart and this intellectual with sort of an edge. She had a black belt in tae kwon do and was semi-bohemian and, you know, like the hot chick on campus.”

Musk pursued a couple of other girls, but kept returning to Justine. Any time she acted cool toward him, Musk responded with his usual show of force. “He would call very insistently,” she said. “You always knew it was Elon because the phone would never stop ringing. The man does not take no for an answer. You can’t blow him off. I do think of him as the Terminator. He locks his gaze on to something and says, ‘It shall be mine.’ Bit by bit, he won me over.”

PayPal Mafia

In the summer of 1994, Elon and Kimbal took their first steps toward becoming Americans. They set off on a road trip across the country. The trip provided plenty of time for your typical twentysomething hijinks and raging capitalist daydreaming. The web had recently become accessible to the public thanks to the rise of directory sites like Yahoo! and tools like Netscape’s browser. The brothers were tuned in to the Internet and thought they might like to start a company together doing something on the web. Musk had spent the earlier part of that summer in Silicon Valley, holding down a pair of internships.

By day, he worked at Pinnacle Research Institute. Based in Los Gatos, Pinnacle was a much-ballyhooed startup with a team of scientists exploring ways in which ultracapacitors could be used as a revolutionary fuel source in electric and hybrid vehicles. The work also veered—at least conceptually—into more bizarre territory. Musk could talk at length about how ultracapacitors might be used to build laser-based sidearms in the tradition of Star Wars and just about any other futuristic film. The laser guns would release rounds of enormous energy, and then the shooter would replace an ultracapacitor at the base of the gun, much like swapping out a clip of bullets, and start blasting away again.

In the evenings, Musk headed to Rocket Science Games, a startup based in Palo Alto that wanted to create the most advanced video games ever made by moving them off cartridges and onto CDs that could hold more information. The CDs would in theory allow them to bring Hollywood-style storytelling and production quality to the games. A team of budding all-stars who were a mix of engineers and film people was assembled to pull off the work. Tony Fadell, who would later drive much of the development of both the iPod and iPhone at Apple, worked at Rocket Science, as did the guys who developed the QuickTime multimedia software for Apple. They also had people who worked on the original Star Wars effects at Industrial Light & Magic and some who did games at LucasArts Entertainment.

Rocket Science gave Musk a flavor for what Silicon Valley had to offer both from a talent and culture perspective. There were people working at the office 24 hours a day, and they didn’t think it at all odd that Musk would turn up around 5pm every day to start his second job.

“Elon said, ‘These guys don’t know what they are talking about. Maybe this is something we can do,’ ” Kimbal said. This was 1995, and the brothers were about to form Global Link Information Network, a startup that would eventually be renamed as Zip2.

Few small businesses in 1995 understood the ramifications of the Internet. They had little idea how to get on it and didn’t really see the value in creating a website for their business or even in having a Yellow PagesÐlike listing online. Musk and his brother hoped to convince restaurants, clothing shops, hairdressers and the like that the time had come for them to make their presence known to the web-surfing public. Zip2 would create a searchable directory of businesses and tie this into maps. This may seem obvious today, but back then, not even stoners had dreamed up such a service.

The Musk brothers brought Zip2 to life at 430 Sherman Ave. in Palo Alto. For the first three months of Zip2’s life, Musk and his brother lived at the office. They had a small closet where they kept their clothes and would shower at the YMCA.

In early 1996, the venture capital firm Mohr Davidow Ventures had caught wind of a couple of South African boys trying to make a Yellow Pages for the Internet, met with the brothers and invested $3 million in the company.

The company’s main focus would be to create a software package that could be sold to newspapers, which would in turn build directories for real estate, auto dealers and classifieds. The newspapers were late in understanding how the Internet would impact their businesses, and Zip2’s software would give them a quick way of getting online without needing to develop all their own technology from scratch.

Zip2 had remarkable success courting newspapers. The New York Times, Knight Ridder, Hearst Corporation, and other media properties signed up to its service. It irritated Musk that Zip2 had become a behind-the-scenes player to the newspapers. He believed the company could offer interesting services directly to consumers and encouraged the purchase of the domain name city.com with the hopes of turning it into a consumer destination.

In April 1998, Zip2 announced a blockbuster move to double down on its strategy. It would merge with its main competitor CitySearch in a deal valued at around $300 million. In May 1998, the two companies canceled the merger. With the deal busted, Zip2 found itself in a predicament. It was losing money. Musk still wanted to go the consumer route, but Derek Proudian, a venture capitalist with Mohr Davidow who had been named CEO, feared that would take too much capital. Then, in February 1999, PC maker Compaq Computer suddenly offered to pay $307 million in cash for Zip2.

“It was like pennies from heaven,” said Ed Ho, a former Zip2 executive. Zip2’s board accepted the offer, and the company rented out a restaurant in Palo Alto and threw a huge party. Mohr Davidow had made back 20 times its original investment, and Elon and Kimbal Musk had come away with $22 million and $15 million, respectively. Elon never entertained the idea of sticking around at Compaq. “As soon as it was clear the company would be sold, Elon was on to his next project,” Proudian said.

In March 1999, Musk incorporated X.com, a finance startup. Musk had considered starting an Internet bank and discussed it openly during his internship at Pinnacle Research in 1995. The youthful Musk lectured the scientists about the inevitable transition coming in finance toward online systems, but they tried to talk him down, saying that it would takes ages for Web security to be good enough to win over consumers. Musk, though, remained convinced that the finance industry could do with a major upgrade and that he could have a big influence on banking with a relatively small investment.

“Money is low bandwidth,” he said, during a speech at Stanford University in 2003, to describe his thinking. “You don’t need some sort of big infrastructure improvement to do things with it. It’s really just an entry in a database.”

It had taken Musk less than a decade to go from being a Canadian backpacker to becoming a multimillionaire at the age of 27. With his $22 million, he moved from sharing an apartment with three roommates to buying an 1,800-square-foot condo and renovating it. He also bought a $1 million McLaren F1 sports car and a small prop plane and learned to fly. Musk embraced the newfound celebrity that he’d earned as part of the dotcom millionaire set. He let CNN show up at his apartment at 7am to film the delivery of the car. A black 18-wheeler pulled up in front of Musk’s place and then lowered the sleek, silver vehicle onto the street, while Musk stood slack-jawed with his arms folded. “There are 62 McLarens in the world, and I will own one of them,” he told CNN.

The next year, while driving down Sand Hill Road to meet with an investor, Musk turned to a friend in the car and said, “Watch this.” He floored the car, did a lane change, spun out, and hit an embankment, which started the car spinning in midair like a Frisbee. The windows and wheels were blown to smithereens and the body of the car was damaged. Musk again turned to his companion and said, “The funny part is it wasn’t insured.” The two of them then thumbed a ride to the venture capitalist’s office.

To his credit, Musk did not fully buy in to this playboy persona. He actually plowed the majority of the money he made from Zip2 into X.com. Even by Silicon Valley’s high-risk standards, it was shocking to put so much of one’s newfound wealth into something as iffy as an online bank. All told, Musk invested about $12 million into X.com, leaving him, after taxes, with $4 million or so for personal use.

PayPal survived the bursting of the dotcom bubble, became the first blockbuster IPO after the September 11, 2001, attacks and then sold to eBay for an astronomical sum while the rest of the technology industry was mired in a dramatic downturn. It was nearly impossible to survive, let alone emerge as a winner, in the midst of such a mess.

PayPal also came to represent one of the greatest assemblages of business and engineering talent in Silicon Valley history. Both Musk and Peter Thiel had a keen eye for young, brilliant engineers. The founders of startups as varied as YouTube, Palantir Technologies and Yelp all worked at PayPal. Another set of people— including Reid Hoffman, Thiel and Roelof Botha— emerged as some of the technology industry’s top investors. PayPal staff pioneered techniques in fighting online fraud that have formed the basis of software used by the CIA and FBI to track terrorists, and software used by the world’s largest banks to combat crime. This collection of super-bright employees has become known as the PayPal Mafia.

From Elon Musk by Ashlee Vance. Copyright 2015 by Ashlee Vance. Published by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.