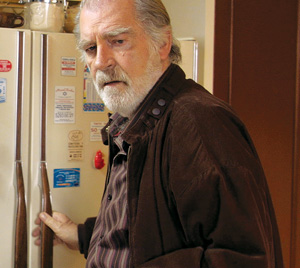

IT IS easy to see why Nora’s Will keeps turning up on the film festival circuit. Mariana Chenillo’s study of a woman’s wake has an unusual setting: the Jewish community in Mexico City. The lead character, the 60ish Jose (Fernando Lujan), might be a figure out of Roth or Bellow—a man who can deny religion easier than he can deny his Jewish roots.

Nora’s Will is about the question of what these roots signify: ancestral wisdom, obligations—or something as simple as having a codified method to deal with pain.

Cinco dias sin Nora is the Mexican title; the double meaning of “testament” and “will power” in the English title is significant. For years, Jose lived across the street from his ex-wife, Nora, in a corridor of high-rise condos near Chapultepec Park. During their marriage, she had tried to commit suicide. After 14 attempts, she succeeded in a lethal overdose.

Death hasn’t stopped her controlling qualities. She’s directing the course of a last Passover Seder through a flurry of notes on the refrigerator that include minute directions on how to prepare the brisket and the side dishes. She even used food to tip Jose off to her death; she sent a delivery boy with a load of perishable frozen meat to his place. After many years of divorce, Jose still had a key to her flat.

The motif of cold meat is essential to the comic side of the film: beside the stuffed refrigerator lies Nora’s corpse itself. She couldn’t possibly have timed her death to cause more inconvenience. Her son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren were on vacation and have to fly in for the emergency.

Jose also learns that there is a double bind: Jewish burials must take place within 24 hours. Yet no one is to be buried until Passover is complete. So Nora’s body lies on the bedroom floor, shrouded, with a platter of dry ice over her stomach.

Her loyal cook, Fabiana (Angela Pelaez), decides to pretty Nora up with makeup and give her a cross to wear. Nora’s sizable vibrator gets excavated, although her two playful young grandchildren who find it decide that it’s really a flashlight.

Jose fights Nora’s posthumous passive-aggressiveness by doing the easy practical things, even if they outrage his relations. The Catholic cemetery will bury Nora at whatever time is required. Hungry and unwilling to follow Nora’s elaborate cooking directions, Jose calls for pizza. This is a scandal to the visiting rabbi and his woebegone assistant Mois (the drily funny Enrique Arreola), a poor convert. The pizza is made with leavened bread; and there’s pork on it.

We’ve all had atheist relatives who liked to stir it up with the devout ones. Jose isn’t quite this kind; rather than being an annoying crank, he’s a mature sad figure, standing firmly on his principle that God doesn’t exist. This estranges him from his bland son and his daughter-in-law.

And Jose harbors some private outrage: sifting through Nora’s files, he discovers that his ex-wife had a sweetheart back when they were married.

During the course of one of Nora’s funerals, there’s a Talmudic reading suggesting what might be done with the corpse of a suicide. As at the graveside of Shakespeare’s Ophelia, it’s questionable whether such a body can be buried in consecrated ground. I don’t want to spoil the actual saying from the first-century rabbi Akiva ben Yosef: it’s a strange contrast of kindness and shocking cruelty. What he prescribes is perhaps more chilly than even the Christian custom of burying the suicide at a crossroads, staked like a vampire. “As if their hearts weren’t broken already,” goes the line in Ulysses.

Nora’s Will isn’t full of exteriors, except the cemetery. It has the closed-in dynamics of a play. The flashbacks don’t look convincing; the soundtrack by Dario Gonzalez Valderrama, at first minimal and unobtrusive, grows too refined by the end of the film. But Nora’s Will evinces the reliable fascination of a story of cultural fault lines chafing, and it also has a constant tone of intelligence. It’s literally unorthodox.

Nora’s Will

Unrated, 92 min.