The fashion industry suffers from its general depiction in film as something frivolous or at least inconsequential, a subject generally fit for gossipy dramatizations–as in Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci–when it’s not the subject of such earnest documentaries as The September Issue (2009). The idea being that the world of fashion has more to do with entertainment than with substantive issues on the order of, say, climate change or wars of aggression.

Invisible Beauty is a coat of a different color.

The new documentary by American fashionista Bethann Hardison and French filmmaker Frédéric Tcheng (Halston, Dior and I) takes a serious look at former model Hardison’s career and especially her role as a fashion industry civil rights activist determined to address the issue of corporate racism. As such, it’s one of the most fascinating films of the year, an eye-opening, personal investigation into who walks down the runway, who gets their face on magazine covers–and who does not.

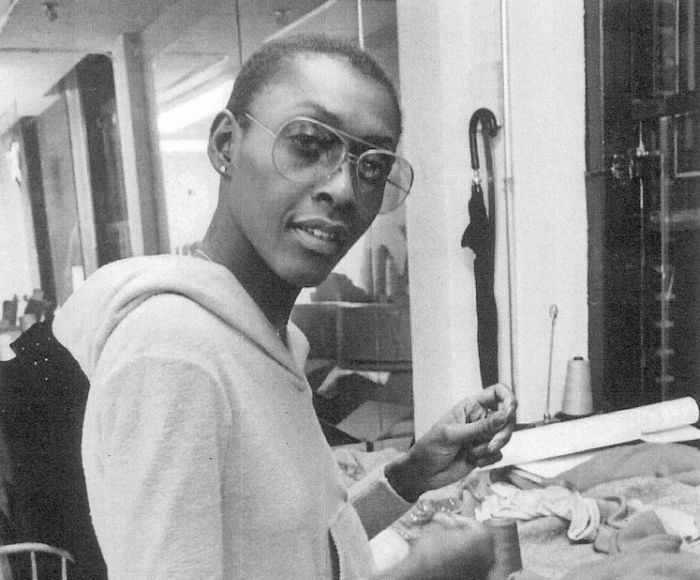

At first, Invisible Beauty seems to be a cheerful profile of the Brooklyn, New York native Hardison and how she broke the ice as one of the first Black fashion models in the 1960s. Hardison spent her early years in Manhattan’s Garment District and was eventually mentored by designer Willi Smith, who, alongside photographer Bruce Weber and fashion critic Robin Givhan, admired her tall, androgynous looks. Her Blackness and the architecture of her face and figure were a much-needed relief from the “white swan” models of the day. And the notorious Versailles fashion show of 1973–when Hardison and 11 other African-American models “conquered France” to cheers from the Parisian press–made her a superstar.

That was not enough. Hardison formed her own modeling agency, attracting the likes of Iman, Naomi Campbell, Veronica Webb and male model Tyson Beckford (in a suit, he looked “heroic”), all of whom testify for filmmaker Tcheng’s camera. Their forte was vibrant personality, in contrast to the chilliness of typical runway models. Meanwhile, their Black Girls’ Coalition advocated and staged benefits for social justice for other Americans, particularly the unhoused.

Hardison noticed something troubling about the fashion hiring scene. After the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the haute-couture world was flooded with pale, robotic models from Russia and other countries, and Black faces abruptly became scarce. Worse, some clients had quietly put out the word that, according to model Webb, “they didn’t want their product to become a symbol of luxury for people of color.”

This advertising bias meant that the faces in their ads did not reflect the percentage of their Black customers. In Hardison’s view, the white-dominated businesses were only interested in showing versions of themselves in their advertising. The result was classic tokenism, with insulting excuses for the institutionalized exclusion of women of color. Hardison’s coalition sprang into action and publicly grilled Estée Lauder, L’Oréal, Lancôme, Calvin Klein and other companies for their racist marketing practices.

Questions arose that still remain pertinent: Do Black models sell? Who is responsible for categorizing Black images for ad campaigns? The documentary points out that fashion advertising is the only U.S. industry that can openly rule out a worker–in this case, the model–on the basis of race. Ironically, real life provided a timely corrective. Soon after Black Lives Matter protests swept the nation, Vogue magazine started using women of color on its covers.

Through all this, the outspoken Hardison maintains her samurai posture (derived from watching Toshiro Mifune movies) and her no-nonsense devotion to racial equality in the “fantasy realm” of fashion. “I’m not trying to help Black people, I’m trying to educate white people,” she explains. “It’s their world. We’re just extras in this.”

Invisible Beauty is a provocative piece of work about a $1.7 trillion global industry that is often not taken seriously, as well as a tribute to a model with much more than just a glamorous presence.

In theaters