We have Bridget Gilman and the members of her Santa Clara University art history class, “Photography and the American West,” to thank for a new exhibit at the de Saisset Museum. The curation of “Virgin Landscape: Representations of Women and the American West” highlights women both in front of and behind the camera lens.

The exhibit’s title—”Virgin Landscape”—is accounted for in one of the cerebral thesis statements that tenuously link the idea of “virgin lands with the rise of women in the American West.” That particular connection between pure and unspoiled land and the photographs themselves remains somewhat elusive (you can almost make it out if you wrinkle your brow and squint a little), but it doesn’t detract from the overall impact of the images themselves.

“Virgin Landscape” is divided into four sections that are more fluid than distinctly held within their appointed categories. The first, “Nudes and Landscapes,” playfully juxtaposes the naked human form next to images from the natural world. Edward Weston asked his model to pose with her arms circling under her left kneecap. On the wall to her right hangs Pepper, a bell pepper whose flesh has also formed and settled into sinuous curves. They are visual cousins, if not twins. Weston manipulates nature—in the female form—to imitate the natural form of a fully grown and ripened pepper.

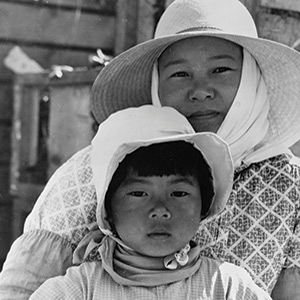

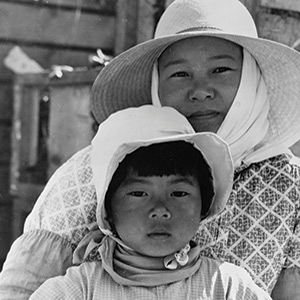

The photographs on display under the heading “Migration and Agricultural Labor” all date back to the late 1930s and belong entirely to Dorothea Lange, best known for the iconic Dust Bowl portrait of the pensive Migrant Mother. Lange’s portraits capture an extraordinarily layered depth of emotion. The human details are so specific and informative. In Singing hymns before opening of meeting of Mother’s Club at Arvin Farm Security Administration (FSA) camp for migrants, California, 1938, three women hold hymnals in their hands, but only one stares directly at Lange’s lens. She cradles a sleeping baby in her right arm. All three are gaunt, nearly expressionless. In this austere setting, it’s hard to believe they’re about to open their mouths to sing in praise of anything.

Judy Dater and Anne Noggle are given their due in the “Gender Identity” category, but for entirely different reasons. Dater’s famous Ms. Clingfree, 1982, retains its satirical pop as a witty, colorful takedown of “woman as housekeeper.” Like many of the other photographers here, Noggle represents a world that’s exclusively female. In other words, it’s virgin territory for male viewers who willfully ignore it, and let it go unseen.

Virgin Landscape

Thru Mar 19

de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara