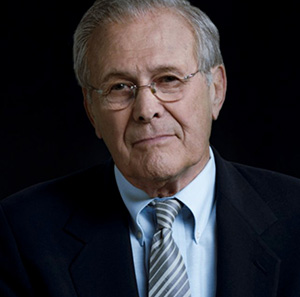

In head and shoulders closeup Donald Rumsfeld shares some anecdotes of his life as a public servant—first as a Congressperson, later as a special envoy, and finally, and ruinously, as Secretary of Defense in the George W. Bush administration. My fellow critic Jeffrey Anderson was bemused by the MPAA warning against “brief nudity” in The Known Unknown, fearing Rumsfeld went naked. Why worry?

Donald Rumsfeld excels at covering his own ass. Natty in a suit, smiling frequently, he glows with a penumbra of satisfaction. The old man thinks he’s Henry Fonda in his later, more scowly parts.

What you do get is the answer to how Rummy sleeps at night, not that the question is asked in so many words. Rumsfeld was right, and when he wasn’t right, it was because the Oxford definition of the phrase “he was wrong” is too restrictive. (Among his “snowflakes,” as Rumsfeld termed his tens of thousands of memos, were notes asking underlings to run to the dictionary to get proper definitions of certain words.) He is right because he will be right eventually, and the rest of the world hasn’t seen it yet. Besides no one could have foreseen what was over the hill. So again, he was right. Or “we lack metrics” to measure defeat or victory. If necessary, the Secretary can cast a passive sentence so that the “he” in it vanishes utterly.

Rumsfeld had the decency to submit a pair of unaccepted resignations after Abu Ghraib, a minor thing in his master scheme; he returns to the phrase “failure of imagination” that prevented us from seeing 9/11. Admittedly, 9/11 happened on his front lawn, so to speak; he was an eyewitness to the aftermath of the strike at the Pentagon, and so perhaps had personal grounds for wanting to stretch the net to include an old nemesis. A moment of great frustration: the revisitation of Rumsfeld’s meeting with Saddam in 1983, greeting him with a smile and a handshake. Asked about it, Rumsfeld shifts the ground, with ease, and without opposition from his questioner Errol Morris. Rumsfeld remembers how scary it was meeting Tariq Ali, who was in military uniform with a pistol in its belt. Morris loses the chance to prompt Rumsfeld back from his memories of Donald Rumsfeld, Man of Diplomacy, and get him back on the subject of the consequences of encouraging Saddam.

This seems to me a minor, often agonizing Morris film, not just because of the eel-like subject, or because we endured the Rumsfeld Show for years. “Must-see television!” crowed some journalist, watching Rummy work the Washington press room. Rumsfeld had right to walk tall: Letterman never had an 80 percent approval rating. There are tedious stylistic quirks Morris recycles from previous efforts: the time-lapsed sun, rising and falling, as the cars zizz by on the Koyanisqatsi Expressway. Meanwhile, we’re listening to Danny Elfman’s tribute to Phillip Glass’s immortal “The Wordless Chorus Serenades the Muse of History, as the Bull Fiddles of Significance Are Sawn.”

There seems so much off limits here: what it was like for this political animal to be locked out of power, and what he did then. Instead, we get Rumsfeld shedding few grateful tears at our luck as a nation. Our nation will not survive much more of Rumsfeld’s kind of luck.

Barbara Tuchman’s book The March of Folly offers three criteria for the most calamitous historical follies: First, the policy must have been perceived as counterproductive in its own time. Second, there must have been a feasible alternative course of action. Third, the folly should be the result of a group policy “and should persist beyond any one political life time.” From these definitions, the war Rumsfeld argued for, obfuscated for, still minces words to defend that Iraq war is equal with Troy, the fall of the Aztecs, and the loss of the American colonies to the British. When Rumsfeld says that Obama continues the Bush policies as proof they were sound after all, in fact what it proves is Tuchman’s third proof of folly. Rather than telling it to the camera, Rumsfeld should be telling it to a judge.

The Known Unknown

103 MIN; PG-13