A man pulls into a parking lot in Scotts Valley, north of Santa Cruz, to pick up another man for the carpool commute over Highway 17 to their tech jobs in Silicon Valley. The driver hands the passenger a square envelope, inside of which is a CD of Patsy Cline’s greatest hits.

“It came,” says the first guy. “Thank God,” mutters the second.

From that otherwise banal moment on an otherwise ordinary day in 1997 came a revolution that has turned the movie and television industries upside down.

That was the day Netflix became possible.

The first man was Reed Hastings and the second was Marc Randolph, who together created the company that has not only changed how millions around the world watch movies and TV, but also is today challenging the hegemony of Hollywood in how entertainment is produced.

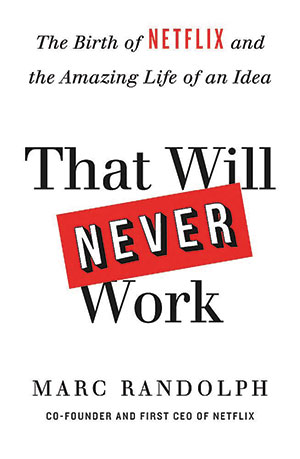

But back then, they were just a couple of schemers, trying to figure out a way to take advantage of this new tool called the internet. Their story is told in Randolph’s new book That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea (Little, Brown).

The two men had already been kicking around the idea of an online video rental business. But the format of the times, the VHS tape, was too big and too heavy to be cost-effective for mail order. They had, in fact, already scrapped the idea before catching wind of a buzzy new format: the digital versatile disc.

They didn’t have a DVDnobody outside of Japan did at that point. But they knew it would be identical to a compact disc. So they bought a copy of Patsy Cline, sealed it in a greeting card envelope and mailed it to Hastings’ house to see how the US Postal Service would treat it.

By that time, Randolph already had 20 years’ worth of direct marketing experience. In his time, he’d sent out millions of pieces of mail.

“I had been to the San Jose central post office,” he says in an interview in Scotts Valley, right across the street from the site of Netflix’s first office. “I’d seen those machines shoot those letters through at 16 gazillion miles an hour and bend them around corners, and all that.”

He was certain that Patsy Clinewhose biggest hit was “I Fall to Pieces”would arrive in pieces. Instead, it made it through intactfor 32 cents, the price of a stamp.

It was not the classic a-ha moment. It wasn’t like BoJack Horseman appeared to them on Highway 17 and laid out the whole glorious future ahead of them, said Randolph. “It was more akin to finding the missing piece of the jigsaw puzzle under the couch. We had this puzzle that we couldn’t complete, so we walked away from it. Then we found the piece that finished it. If the book is about anything, it’s not an epiphany story, nor is it some brilliant visionary CEO story either. It was just luck. Lots of luck.”

Randolph, 61, was the original CEO of Netflix, but he left the company in 2002, and his new book is an often funny, sometimes harrowing romp through those early years of getting established in Scotts Valley. If the idea to send DVDs through the mail were the company’s only innovation, it probably would have quickly sank in the swamp of internet get-rich schemes, particularly given the absolute dominance of Blockbuster and its competitors in establishing consumer home viewing habits.

The innovations had to keep coming, and Randolph and Hastings were up to the job. In the early days, when the DVD began to eclipse VHS, Randolph recalls standing in the middle of the company’s San Jose warehouse, looking at more than 100,000 DVDs.

“‘Why are we storing these here?'” he remembers thinking. “I wonder if there’s a way to store them at customer’s houses instead. Then Reed said, ‘Let’s let them keep the DVDs as long as they want. When they’re done with one, we’ll send them another one.'”

That was quickly followed by two other innovations, which, when taken together, spelled doom for the Blockbuster era: charging customers a flat monthly subscription fee rather than making them pay for each movie, and creating the famous Netflix queue in which customers could create a priority list of what they wanted to see and have it automatically delivered. Netflix’s shipping practices were a big part of its hegemony in the market. The company calculated that strategically placing about 60 mailing hubs around the country could ensure next-day delivery for 95 percent of the US mainland (and the message sent out to customers that their next choice was on its way prefigured the dopamine hits that later became a central part of the social media revolution).

Early on, before Patsy Cline, Randolph and Hastings had developed a ritual. As the two took turns driving over 17, Randolph would pitch Hastings an idea. And Hastings would, more often than not, deliver the verdict from which Randolph got his book title: That’ll never work.

Randolph’s pre-Netflix ideas were, in hindsight, not exactly brilliant: home-delivery shampoo, personalized dog food, custom-built baseball bats and surfboards. The Netflix idea developed in stages, after hours of research and discussion, and through a series of timely actions and lucky breaks. The Patsy Cline moment was a turning point, but, said Randolph, there was no light bulb, no apple falling on Newton’s head, no epiphany.

“Distrust epiphanies,” he writes in That Will Never Work. “Epiphanies are rare. When they appear in origin stories, they’re often oversimplified or just plain false.”

Before he met Reed Hastings, Randolph was a marketing veteran. He was a co-founder of MacUser magazine and started two of the first mail-order catalogues for computer products in the pre-internet days. He worked for years at Borland International, based in Scotts Valley. Eventually, he helped found a start-up that was bought by a software development company run by Hastings, who decided to keep Randolph on after the merger.

Randolph’s tale takes on many of the roller coaster elements of start-up culture, from finding funding to recruiting talent to building an inventory to deciding on a name. Among the names that lost out to Netflix: CinemaCenter, Videopix, SceneOne, E-Flix and NowShowing. Of the final choice, now a familiar touchstone around the world, Randolph writes, “It wasn’t perfect. It sounded a little porn-y. But it was the best we could do.”

The site launched in April 1998, and the book provides a tick-tock account of the company’s first days and weeks.

Predictably, the server crashed the day of the launch. In the days before the company’s trademark red envelopes clogged mailboxes coast to coast, Netflix needed a marketing break. That came from an unlikely source: President Bill Clinton, who was at the time consumed in scandal. Randolph decided to offer Clinton’s full grand jury testimony on the Lewinsky scandal on DVD to all customers for 2 cents. That stunt got the media’s attention, and suddenly Netflix was news.

By the next year, Hastings replaced Randolph in the CEO’s chair, Randolph took on the role of company president and Netflix moved north up Highway 17relocating from Scotts Valley to Los Gatos, largely, Randolph says, to attract top talent.