Blind Benevolence

Six years after founding the first California mission in San Diego, Friar Junipero Serra wrote a letter requesting that four Indians who had dared flee from Mission Carmel be severely whipped two or three times.

That little known request was made to Spanish military commander Fernando de Rivera y Moncada on July 31, 1775. In the letter, Serra cavalierly describes the search party that recaptured the runaways as going to the mountains “to search for my lost sheep.” The request that Rivera flog the Indians is a chilling contrast to the pervasive image of Serra as a gentle and kind priest who never mistreated the mission Indians. In reality, Serra, a respected theologian who considered Indians subhuman, had hurled a cloak over the entirety of California’s coast, enveloping it in a darkness filled with death and suffering. Not only does Serra ask Rivera to lash the Indians, he also inquires if the commander needs shackles to punish them further: “If your Lordship does not have shackles, with your permission they may be sent from here. . . .”

That single revelatory sentence from Junipero Serra’s own pen is indicative of the horrors that befell the Indians that Serra and his fellow Franciscans had enticed into those first missions. What were shackles and chains doing in a mission where friars and Indians supposedly worked together in a loving atmosphere? Additionally, what authorization was given to Serra and the friars to enslave not only the Indians, but also their children and their children’s offspring and impose forced labor on them? Serra’s mandate from the Spanish king was to educate the Indians and then release them. Instead, he took it upon himself to effectively imprison them for life and use the Native Americans as forced labor.

Underlying the Franciscan friars’ disdain of the Indians was the fact that they valued the souls of their captives far more than their material existence on earth. The Friars’ utmost goal was to ensure that upon death those souls, kept free of sin, ascended to heaven, thereby fulfilling their Franciscan vows to Christianize the Indians. The Franciscans thus tightly restrained the Indians’ ability to enjoy life or engage in amorous adventures. It mattered little if the Indians suffered. Their deaths were not mourned by the Franciscans, but were, rather, rejoiced as another soul sent to heaven and God.

Indians who grieved and wept over the loss of a loved one were ordered whipped. Likewise, Indian mothers who suffered a miscarriage were not allowed to grieve over losing their child. Instead, they were accused of committing abortion and at times whipped. The Franciscans would punish these women by having them cradle a grotesquely carved figure of an infant and, humiliated, stand outside the mission church. This harsh treatment was aimed at preventing Indian women from aborting their pregnancies in an attempt to spare their infants from suffering the intolerable conditions of existence within the missions.

A robust birth rate was considered critical by the Franciscans to counter the terrible death rate that developed in each compound. Friars harangued Indian women to have more babies. Yet despite these efforts, the death rate within the missions was so appalling that more Indians died than were born annually, crippling an Indian population that was already reeling from disease, malnutrition, depression, and physical abuse.

Those who dared criticize Serra and his Franciscans for their treatment of the Native Americans risked being crushed by the power of the Roman Catholic Church, with its power of excommunication, or being literally torn to pieces by the Inquisition, which could conduct an investigation using horrendous means of torture against anyone who dared challenge the church or its hierarchy.

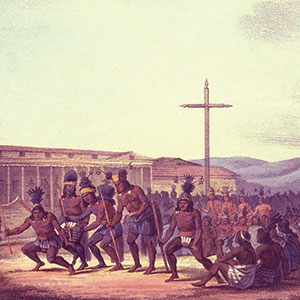

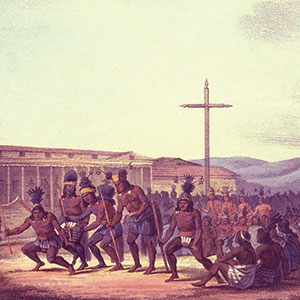

Despite that threat, the Spanish military commanders and governors of California opposed the friars’ use of the Indians as forced labor to work the missions’ enormous tracts of land, although they had to carefully choose their battles when it came to confronting the powerful Franciscans. Spanish officials feared that—bolstered by captive Indian labor—the missions would eventually control the economy in California by growing the power of their huge agricultural holdings, estates which covered hundreds of thousands of acres of the best land that California had to offer. Those lands provided rich pastures where mission livestock herds numbering in the tens of thousands could graze and quickly multiply.

Spanish military commanders and governors attempted to delay the founding of new missions by stipulating that the soldiers to be assigned to those compounds could not be spared to hunt runaways, or join the friars in swooping down on neighboring villages and threatening the Indians with a hellish afterlife if they did not join their missions. This tactic was effective and slowed down the missions’ advance across the California coastline. Still, while Serra was himself restricted to founding nine missions, his wily successors were able to eventually entice Spanish officials into permitting them to found twelve others, stretching along the Alta California coastline from San Diego to San Francisco Bay.

Cruelty toward the Indians was a common denominator in each mission. One friar, Geronimo Boscana, who studied the Indians’ beliefs, wrote they “. . . may be compared to a species of monkey . . . .” Others, including Serra’s successor, Friar Fermin Francisco de Lasuen, held similar thoughts, calling them ungrateful liars who were never to be trusted

The mission Indians, called neophytes by the friars, had terrible, sadistic punishments inflicted on them by the Franciscans. In one incident, the leader of a group of recaptured runaways had his hands and legs bound, then had the skin of a newly slaughtered calf tightly wrapped around him and sewn shut. He was tied to a post and left to suffocate under a hot sun that slowly shrank the calf skin. The description of that nightmarish event was provided by a Russian seal hunter, Vassili Petrovitch Tarakanoff, who had been captured on the coast in 1815 and held for several years in mission San Fernando before being released.

There were other similar incidents of great cruelty. At Mission San Francisco, the captain of a trading ship came upon Franciscan friars using a red hot iron to burn crosses into the faces of a group of men, women, and children who had tried to escape from the mission. In Southern California, thugs appointed by friars from the ranks of their Indians at Mission San Gabriel used a bullwhip, nearly ten feet long, to beat the natives.

One distinguished visitor to Mission Carmel was shocked at the fetid squalor in which the Indians were forced to live. Jean-Fran ois de Galaup, Comte de Laperouse, a French admiral leading a major expedition ordered by King Louis XVI to explore the Pacific Rim, arrived at Monterey in 1786 amid pomp and circumstance. He commanded two ships carrying many of France’s renowned scientists.

Escorted to Mission Carmel, Laperouse was appalled at what he saw. Bedraggled Indians, some in shackles and stocks, were being walked to a work site accompanied by Indian guards who swung whips to ensure their staying together. The sight, he wrote in his log, was no different than the slave plantations his expedition had visited on the islands of the Caribbean. He described the policies of the Franciscans toward the mission Indians as “reprehensible,” adding they were beating the Indians for violations that in Europe would be considered insignificant.

As the first non-Spanish European to visit the mission, Laperouse had expected more from the Spanish settlement. Instead of cathedrals and beautiful Spanish colonial buildings and courtyards, he found only crudely made adobe huts with roofs made of branches and twigs (the design of the missions would be greatly improved years later). For Laperouse, it was a sordid sight. The French admiral wrote how much better it would be if the Franciscans treated the Indians in a manner that gave priority to their individual human rights, rather than ensnaring them with a rigid and relentless set of rules.

Serra and his fellow Franciscans obviously did not share this attitude. For them, the mission Indians were to be treated more like mere chattel. They were to be fed, encouraged to marry and reproduce, kept free of sin, provide forced labor, and ultimately give up their souls to God. Serra’s and the friars’ lack of compassion for the Indians stemmed from their minds being mired in the dark ages, suffused with the attitude that Spanish Catholicism was to be rigidly followed and that Spaniards were members of a master race—all others and non-Catholics were beneath them. The innovations in philosophy and technology wrought by the Renaissance meant little to them.

A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions

By Elias Castillo

Craven Street Books