As the end of the first quarter of the 21st century nears, creating and consuming music is easier and cheaper than ever.

Despite the resurgence of vinyl records over the past decade or so, streaming is still the number one way that people around the world get their music. And why not? In this age of streaming content, people don’t want to wait days or weeks to buy the new hot record when they can hear it the day it’s released.

With digital compression technologies developed in Germany and online players emerging from labs and factories in London, Southern California and South Korea in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the stage had been set for the digital music revolution. The first online music market emerged in Silicon Valley’s periphery through what has become a bit of a forgotten tale in an industry now dominated by giants.

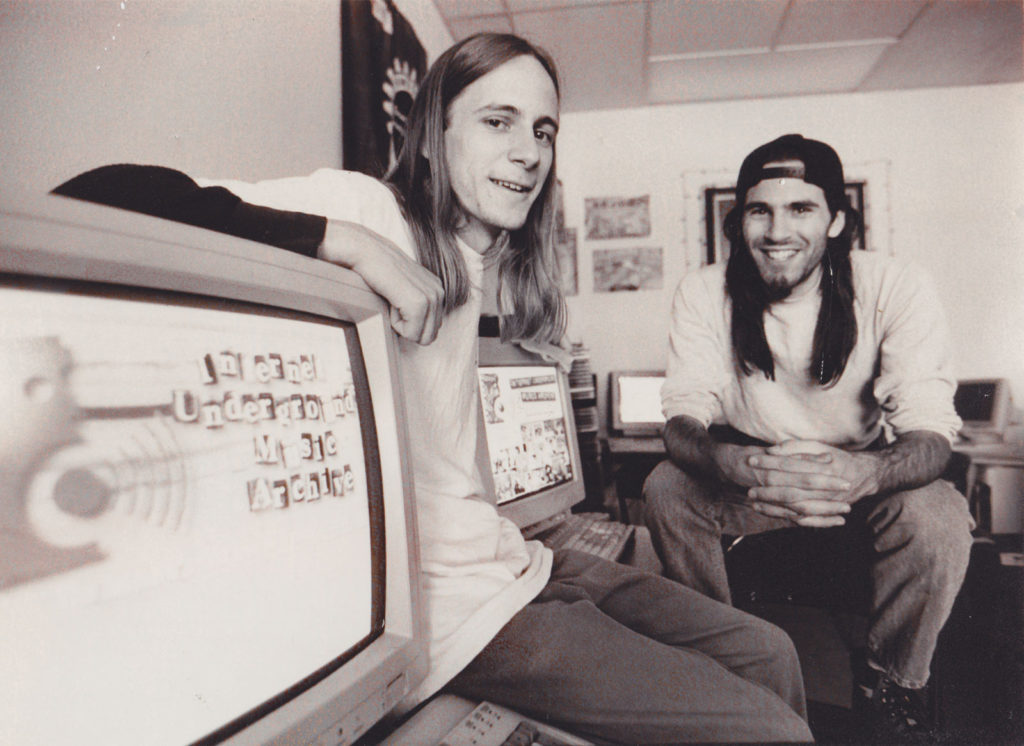

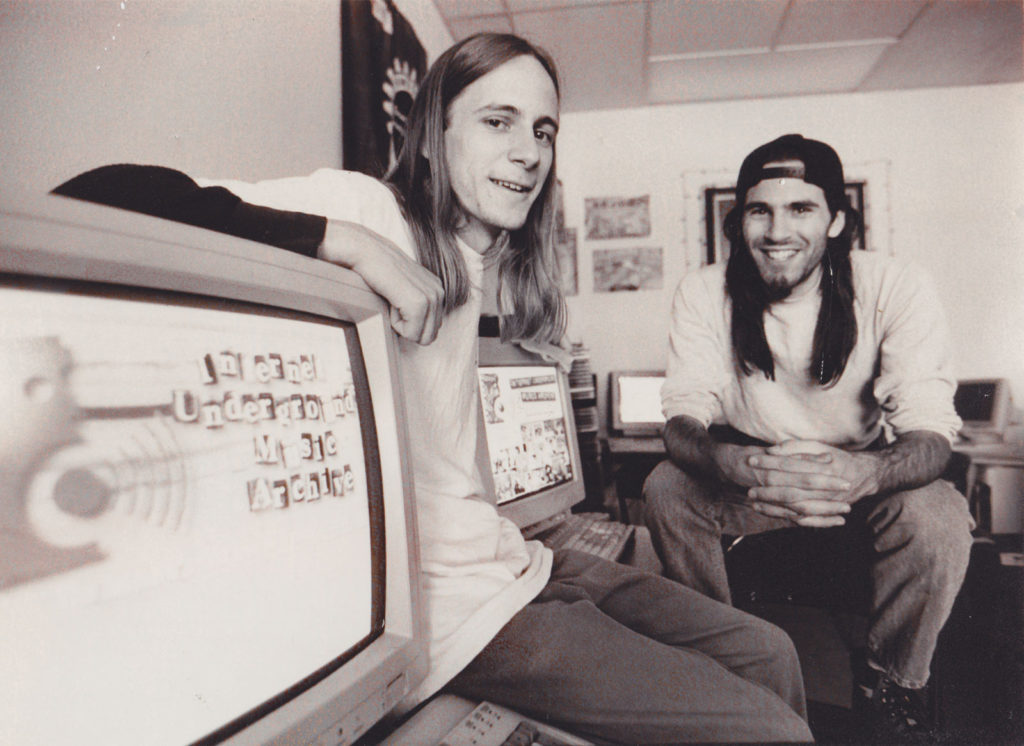

The Internet Underground Music Archive, or IUMA (pronounced “Eye-You-Ma”), was founded in 1993 by two UC Santa Cruz students, Rob Lord and Jeff Patterson, along with UCSC alumnus Jon Luini. It was the first online source not only for independent, unsigned bands but for online music anywhere.

On April 27, the original founders will reunite in Santa Cruz with their friends, family and former co-workers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of an idea that was years ahead of its time.

How did a few idealistic students literally change the world? And why don’t more people know about it?

According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, a nonprofit that has represented the recording industry’s interests since 1933, streaming represented 67.3% of global music revenue in 2023. That’s not accounting for pirated music, through which roughly 30% of global listeners get their tunes.

Billboard.com reports that 2023 also saw the streaming industry continue to grow. On-demand audio and video streams rose 14.6% last year, improving on the 12.2% in 2022. Last year also saw the global market reach a record-breaking 4 trillion streams fueled by more non-English-speaking artists creating music and—of course—the global phenomenon that is Taylor Swift.

But in 1993, the idea of downloading or streaming music from the computer seemed like technology from a Ray Bradbury novel—inevitable but still in the distant future.

“One quote from Rob I always liked was ‘the bleeding edge,’” Luini says. “It captures the essence of what it was all about. It was beyond the cutting edge.”

For those who don’t remember or weren’t born yet, 1993 was a time of great change around the world culturally and politically. Anything seemed possible, and the future looked bright.

The world was still restructuring itself after the collapse of the U.S.S.R. at the end of 1991. A spry and saxophone-playing-but-not-smoke-inhaling Bill Clinton started his first year of what would be an eight-year presidency. Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” from The Bodyguard soundtrack was the chart topper, but that chart also included names like Madonna and Nirvana. Amazon.com was still a year away from creation.

And this thing called the internet was slowly seeping its way into the public forum.

OVER THE ELECTRIC GRAPEVINE

Though the groundwork for the internet was laid in the 1960s, when ARPANET created the first true computer network, in the early 1990s most people didn’t have home computers. And if they did, they used a dial-up network, with its screeching, dying-robot noises. It wasn’t until 1993 that the hyperlinks of the World Wide Web began to form the modern internet.

This was the world into which IUMA was birthed.

“Rob and I went to high school together in Southern California,” Patterson explains. “He and my sister worked at the cool record store in town—Tempo—and I worked at the commercial record store, Music Plus.”

Though arriving at UC Santa Cruz at different times, the two reconnected. At the time Lord was studying computer science under the late Professor David Huffman. It was Huffman who first invented minimum data encoding—essentially, data compression.

“That’s when things started coming together, music and digital signal processing,” Lord says.

“It was also exciting because I had used dial-up networks but not on the internet proper before coming to UC Santa Cruz. There was an open standards global data network that I had heard about, but it blew my mind we got it in school.”

The problem, or possible blessing: With the internet still in its swaddling clothes, nobody really knew what to do with it. With no search engines, techies would write codes, each person having their unique signature, and put it out into the digital abyss.

“I would go through every FTP* [Network Time Protocol] site, any site that was online,” Luini laughs. “If you stayed up all night you could scour them all?”

Yes, that’s right. Three decades ago, someone could actually absorb the whole internet.

“You would do your best to find things by connecting with other people,” Lord confirms. “Going from one hyperlink to the next without a resource to guide you.”

Both Lord and Patterson always wanted to combine music with tech. For Lord’s high school senior quote, he said he “wanted to make robots that sing.” Prior to transferring to UCSC, Patterson attended UC Berkeley at the Center for New Music and Audio Technology. He was also in a local band called the Ugly Mugs, who were in the process of recording a demo tape but had no means of distribution. That’s when Patterson remembered an email Lord sent about a 10 to 1 audio data compressor he created.

“So we started talking about what we could do with it,” Patterson remembers. “And Rob had the idea that this could change the world.”

Despite living on a student’s budget, Patterson bought the proper encoding equipment and set Lord’s idea to work, compressing audio into MP2 files.

“I still remember him coming over to my house and us recording This Mortal Coil and Primus,” he states.

Testing the demos on tiny Logitech speakers, the duo knew they were on to something but needed a bigger field to ignite their idea.

Enter Jon Luini.

A UCSC graduate and musician, Luini also volunteered at the university managing resources like the FTP server.

“I got an email one day from these guys saying, ‘Hey, can we get some space on the UCSC FTP server?’” Luini recalls. “I said, ‘Probably, but what do you want to use it for?’”

They shared their idea and he was immediately on board.

“Jon was further along in computer science than either of us,’” Lord admits. “And he was in three bands, so he was the perfect match for what we were doing.”

He pauses to laugh before adding, “I remember telling Jeff, ‘He’s in three bands! That will double our archive!’”

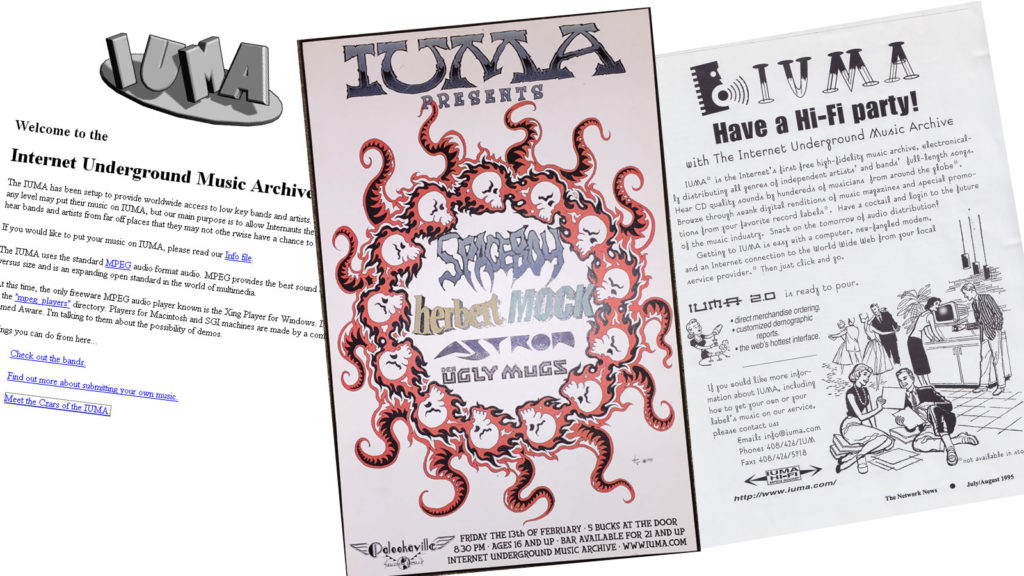

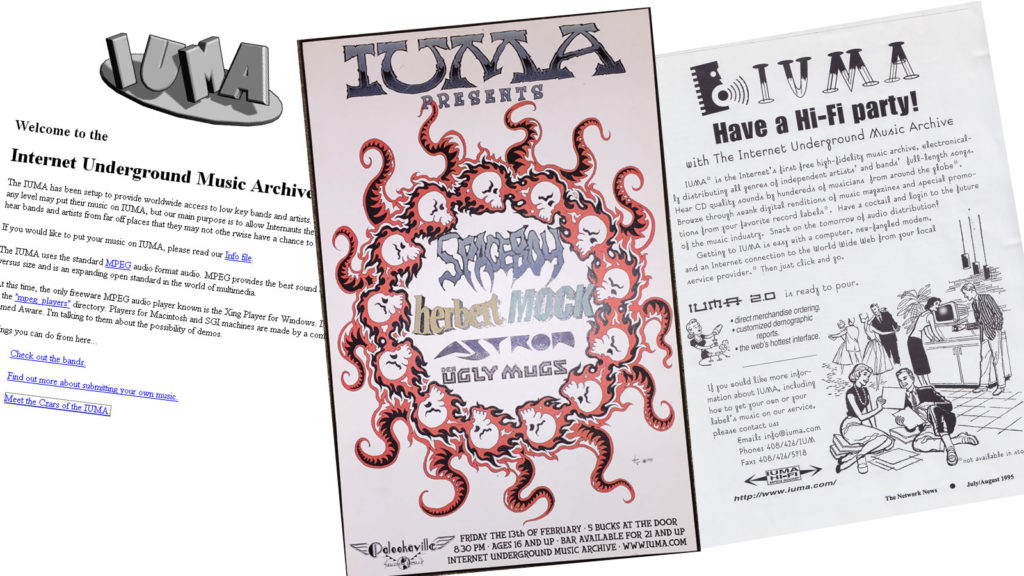

They named the project the Internet Underground Music Archive and posted a call-to-arms for local bands to start digitizing their music. The idea was simple: bypass the major labels to encode and distribute music from underground, independent, underrepresented acts.

“There was a hotbed of activity in Santa Cruz at that time,” Luini explains. “Especially for such a small town.”

“Like a lot of early internet, there was a notion of what became known as the democratization of media,” Lord explains.

It was this ethos behind IUMA that grabbed the attention of local musicians. Plus, advertising it as a way to reach millions of potential fans probably didn’t hurt either. Soon IUMA was converting music from Bay Area bands the Fucking Champs, the Groove Pigs and the Himalayans.

Soon they received solicitations from countries around the world such as well as small indie labels across the U.S.

Basically it was as do-it-yourself as one can get.

“There was definitely an issue of ‘your computer wasn’t where you listened to music,’” Luini says. “But there wasn’t a pushback of ‘you guys are crazy.’ Instead people were saying, ‘you guys are ahead of your time’—even if it took all night to download one song.”

THOSE DAMNED BLUE-COLLAR TECHIES

Within two months of launching, IUMA had already caught the attention of big media with ex-MTV veejay Adam Curry offering to promote the archive on MTV’s website. Lawyers who saw the potential in the future of music offered legal advice pro bono in the event of any cease-and-desist letters from record companies.

After all, as Lord told the Mercury News in a front-page article published January 31, 1994, “We want to kill the record labels.”

IUMA received another national boost on March 9 of that same year when it was featured on the CNN program Showbiz News, featuring a 23-year-old Lord and 20-year-old Patterson.

In those early days IUMA was operating more like an anarchist group instead of a company. For example, they took donations from bands to keep the archive going. Lord, Luini and Patterson would often go back and forth on whether or not IUMA was a business, a collective or something else.

As IUMA grew larger, with other programmers joining their cause and more checks from artists coming through, they decided to officially realign the archive as a business. Soon after, they moved from campus to an office above the Blue Lagoon club in downtown Santa Cruz.

“It was the realization that just because you’re a for-profit company doesn’t mean you can’t do good things,” Luini states. “If we wanted to move forward we had to restructure.”

For a bunch of creatives, however, the business end wasn’t the easiest.

“All of that was not only foreign, but largely distasteful,” Lord says.

For the next two years IUMA would continue to grow and showcase underground artists while generating revenue to keep the archive alive. They also moved a second time, relocating to the Old Sash Mill in Santa Cruz, near the current Woodhouse Brewery, where IUMA will host its 30th anniversary party.

Through it all, IUMA kept its DIY ethos alive and maintained a practice of always paying artists for whatever online revenue they accrued via banner ads.

“We would pay bands something like 50% of the ad revenue generated by their page,” Patterson says with a laugh. “And we didn’t have minimums; we’d pay you regardless. We didn’t hold onto any of the money. So even though nobody was making any real money, it was at least legitimate.”

Allen Whitman, ex-bassist and founding member of local surf rocker band the Merman and a former bassist for guitar virtuoso Joe Satriani, was one of those artists who received an IUMA check.

“I saved it because it was nine cents,” he chuckles. “I was like, ‘This is beautiful.’ I was so happy with it because it was perfect. They were doing it correctly.”

Whitman first met Luini through a mutual artist friend who used to make posters for the Mermen. Luini already knew about the band and IUMA began working extensively with the Mermen.

“We both wanted to see everybody win,” Whitman remembers. “We were all on fire; there was nothing we couldn’t do.”

The Mermen even headlined the IUMA Fest in October 1995, held at the now-defunct Palookaville club.

“That was a special and unique time when people gave a shit,” Whitman says. “The concept that we could connect to anyone around the world while cutting out the middleman of the existing record industry.”

Like so many independent artists today, Whitman continues to carry the torch of DIY music with last year’s self-released solo album—Monogatari no Fūei—and his new band, Five Day Miracle Tent Crusade.

As IUMA continued to grow and make waves in the record industry, Lord, Luini and Patterson were invited to meet with representatives from Geffen Records and Warner Brothers (now Warner Music Group).

“There were people visionary enough to realize this was coming and wanted to understand it, so they did do stuff with us,” Luini explains.

That led IUMA to be the first company to put music online from some of the biggest names in the ’90s, like Madonna, Eric Clapton and Soul Coughing.

However, just as Kurt Cobain wrote, “It’s better to burn out than fade away” during his final moments, IUMA’s star began to implode.

THE TOYS GO WINDING DOWN

Only two years after forming the company, Luini left in 1995 and Lord would be gone by the beginning of 1996.

Along with the organizational and financial models, Luini says he felt he was drawn in too many directions. In addition to the archive, he was heavily involved in IUMA working with the House of Blues to create the very first internet livestream. Luini also spent much of his time focused on the music magazine IUMA and journalist Michael Goldberg launched called Addicted To Noise. It all became too much, too soon.

“I think it became obvious that my attention was not in one place,” he admits. “My memory is that it didn’t seem like the right place for me to continue being at.”

The internet was also growing at a rapid pace.

In 1995, an estimated 15 million users were on the internet worldwide. Within a year, the number tripled to 45 million people. This also meant more coders were creating their own algorithms and software, often copying certain parts of IUMA’s model. The introduction of search engines and browsers furthered the technological advancements.

To adapt to the speed of these advancements, IUMA would have to make changes. Lord says, “I think that was a lot to ask of UCSC college students with a good idea, a lot of heart and sweat … to change the organizational model every three months.”

In 1999, IUMA was bought by online music company eMusic, which moved the central office to Redwood City. Ideally it would’ve been the perfect way to keep IUMA alive and well in the long term. However, that was also the same year a new, unforeseen competitor was launched onto the world: Napster.

Still, IUMA seemed to thrive during the year 2000. That year they launched a campaign to give $5,000 to the first ten couples who named their baby “IUMA,” and surprisingly—or maybe not—several families took them up on the offer.

That was the same year IUMA threw its “Music-O-Mania” NCAA-style tournament. It was the largest online Battle of the Bands, with winners flown to San Francisco to open for Primus.

By 2001, Napster was at the height of its popularity. Much of the media’s attention became focused on the legality of online music, with artists like Metallica’s Lars Ulrich leading the charge to shut it down.

“eMusic’s stock went from like $31 a share to 17 cents a share in like a one-week period,” Patterson says.

“Napster was coming up and all these lawsuits were hitting, plus congressional hearings with people from the record industry talking about copyrights.”

Unfortunately for IUMA, the rapidly changing environment and eMusic’s massive losses led to the parent company being bought by Universal Music. However, Universal wouldn’t complete the acquisition until eMusic cut IUMA’s funds.

“We brought everyone into the conference room and said, ‘Hey, guys, eMusic is shutting us down but we have a plan to resurrect it,’” Patterson reflects.

“So basically everyone just started working for free to keep the lights on. It felt like the old days, where everyone just wanted to keep going.”

In 2002 IUMA was purchased a second time, now by Italian music company Vitaminc. Yet, the writing was already on the wall and that year Patterson—the last remaining founder—decided to walk away.

“After I left, that’s when things sort of went into autopilot,” he says. “I don’t know if after 2002 anyone touched the servers again.”

By 2006 IUMA had completely disappeared from the internet, symbolic of the way a once public web was quickly becoming privatized. But like all good ideas, there were still some true believers.

In 2012, Jason Scott the founder of Textfiles.com—a website that’s dedicated to preserving the digital history of early code writers—announced much of IUMA’s discography was reposted on the nonprofit digital library, Internet Archive. On his personal blog Scott said the collection represented a staggering “25,000 bands and artists and over 680,000 tracks of music.”

IS IT LUCK?

On the eve of their 30th anniversary meetup, the original IUMA founders look back with mixed feelings at their idealistic adventure.

Patterson sees IUMA as an inevitable step in progress. They just happened to jump on it first.

“Something we did caused a spark to speed things up, and that feels good,” he states. “We played an essential part in getting the conversation happening.”

“I think the spirit of IUMA lives on in so many different places and in so many different ways,” Luini adds. “The same things that drove me to care about what we were doing there are the same things that drive me to care about now. The sad thing is there are still the same problems out there to be solved. It’s not just music. There needs to be an ecosystem where people can do what they are passionate about and still survive without selling their soul to a job.”

Lord agrees. In 1998 he launched Pioneers of the Inevitable, a software development company that created an open-source music jukebox called Songbird, which—not surprisingly—has an updated resemblance to IUMA.

“I’ve made a career out of doing innovations in digital media,” he says. “But there’s still a lot of innovation to be done. A lot of big companies don’t give us the best implementation of what digital music can be. [IUMA] kicked something off. We didn’t finish it, and who knows if it will ever be ‘finished.’”

Lord, Luini and Patterson invite all past IUMA employees and friends to join them at Woodhouse Brewery in Santa Cruz on April 27.

* References changed to FTP post-publication.

** Joe Satriani’s current bassist is Bryan Beller.